WASHINGTON - No batteries required: Scientists are creating a biological pacemaker by injecting a gene into the hearts of sick pigs that changed ordinary cardiac cells into a special kind that induces a steady heartbeat.

The study, published Wednesday, is one step toward developing an alternative to electronic pacemakers that are implanted into 300,000 Americans a year.

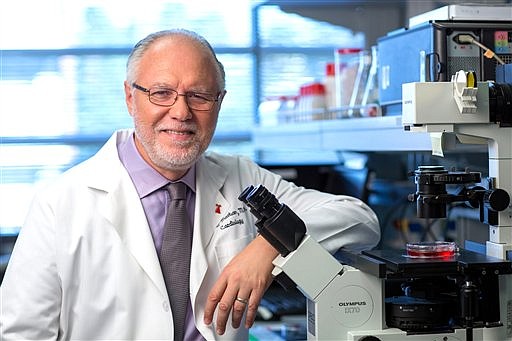

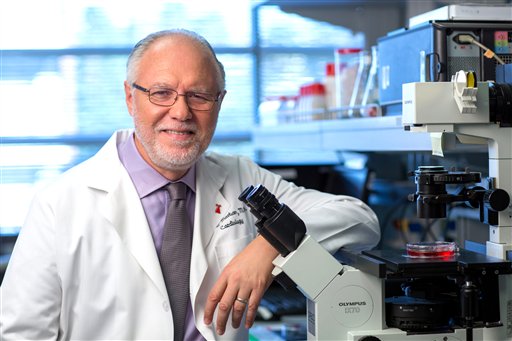

"There are people who desperately need a pacemaker but can't get one safely," said Dr. Eduardo Marban, director of the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, who led the work. "This development heralds a new era of gene therapy" that one day might offer them an option.

Your heartbeat depends on a natural pacemaker, a small cluster of cells - it's about the size of a peppercorn, Marban says - that generates electrical activity. Called the sinoatrial node, it acts like a metronome to keep the heart pulsing at 60 to 100 beats a minute or so, more when you're active. If that node quits working correctly, hooking the heart to an electronic pacemaker works very well for most people.

But about 2 percent of recipients develop an infection that requires the pacemaker to be removed for weeks until antibiotics wipe out the germs, Marban said. And some fetuses are at risk of stillbirth when their heartbeat falters, a condition called congenital heart block.

For over a decade, teams of researchers have worked to create a biological alternative that might help those kinds of patients, trying such approaches as using stem cells to spur the growth of a new sinoatrial node.

Marban's newest attempt uses gene therapy to reprogram a small number of existing heart muscle cells so that they start looking and acting like natural pacemaker cells instead.

Because pigs' hearts are so similar to human hearts, Marban's team studied the approach in 12 laboratory pigs with a defective heart rhythm.

They used a gene named TBX18 that plays a role in the embryonic development of the sinoatrial node. Working through a vein, they injected the gene into some of the pigs' hearts - in a spot that doesn't normally initiate heartbeats - and tracked them for two weeks.

Two days later, treated pigs had faster heartbeats than control pigs who didn't receive the gene, the researchers reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine. That heart rate automatically fluctuated, faster during the day. The treated animals also became more active, without signs of side effects.

"In essence, we created a new sinoatrial node," Marban said. "The newly created node then takes over as a functional pacemaker, bypassing the need for implanted electronics and hardware."

It's a different type of gene therapy, and a few other genes that might switch one cell type to another are under early study to treat deafness and diabetes, Marban said.

It's not clear how long these newly reprogrammed cells would keep working, cautioned Drs. Nikhil Munshi and Eric Olson of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who weren't involved in the research but analyzed the findings in a journal commentary.

Also, the gene was delivered by putting it into a virus engineered to disappear relatively soon afterward. The Texas pair noted that some virus particles landed in the lung and spleen, and that longer studies are needed to rule out safety concerns.

Still, the results "provide an encouraging indication that a biological pacemaker might eventually be ready for human translation," Munshi and Olson concluded.

The heart rate did start to slow a little toward the study's end, but Marban said there's no reason to believe "that the two weeks is somehow a magic cap. We have every reason to believe that this could go on longer."

He said longer-term animal studies are underway, and he hopes to begin first-step human studies in about three years.