Signals SwitchedCity officials hope to create hubs where travelers can get off the train and hop on an electric shuttle, a bike, a car or even a Greyhound bus. Since some of the train routes overlap with CARTA's existing routes, the agency would have to rework its system to align with the light rail program, said Lisa Maragnano, executive director of the Chattanooga Area Rapid Transportation Authority."We could be the connecting point," she said.Each weekday, 6,300 people ride one of CARTA's 16 fixed routes, along with 2,600 more who ride the free shuttle.Maragnano is hopeful that light rail can work here. She doesn't think it will drain CARTA's current annual ridership of 1.8 million, but rather bring new customers into public transportation, freeing up the interstates."If they have a choice, it's comfortable, and they're not sitting in traffic, they'll probably look at it more," she said. "It'll be a lot more cost-effective. And time-effective."Source: CARTA

You learn to ignore the rusty rails that snake through the heart of Chattanooga, a city at once defined and confined by its choo-choo heritage.

Commuters in cars and buses have grown accustomed to passing over, under and around Chattanooga's industrial legacy, a birthright that today lies partially obscured by geography, trees and time.

Few remember that electric trolleys once trundled down the city's boulevards, up its mountains and into its neighborhoods.

That's because a succession of administrations here and in cities across the nation paved over the rails and replaced the trams with buses and wider roads.

But rail travel here could be poised for a comeback if a plan to resurrect the city's underused infrastructure passes muster with the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The federal agency could award Chattanooga $400,000 toward a $700,000 study that would pave the way for light rail transport within the city limits, an estimated $35 million project that would transform Chattanooga's underused rail infrastructure into a fully formed transit system.

It's a gamble that could redefine the way people move about the city, breathe new life into depressed parts of town and pump new development dollars into Chattanooga's business core.

It's also a bet that could backfire on Mayor Andy Berke, exposing the city to millions of dollars in operational costs to maintain an untested system that may not take people where they want to go.

Capital costs aside, rail systems cost millions of dollars to operate each year, and ticket sales almost never cover the tab. Buses are a cheaper way to add transportation options in depressed areas, and it's far easier to modify a bus route than it is to move a rail station. Not to mention Chattanooga's challenging geography, which would require rail planners to build bridges, dig tunnels and move mountains to connect the city's North Shore to its southern border with Georgia.

Those objections and others have killed previous rail projects.

But this time could be different.

ALL ABOARD

From the corner of Third Street and Holtzclaw Avenue it's just a short walk from here to the Chattanooga Zoo, Warner Park or the National Cemetery. Aging commercial developments give way to sprawling inner-city communities.

This crossroads, which links Chattanooga's downtown core to its poorer eastern neighborhoods, is the central axis for the city's new light rail project. A new train station here could spark business and residential development, city officials say, as well as connect residents of neglected neighborhoods -- many of whom don't own cars -- to jobs in other parts of the city.

"Because rail is permanently in the ground, it has a better effect of spurring economic reinvestment in neighborhoods that really need it," said Blythe Bailey, city transportation director. "As with any transportation option, the more ways to get where you need to go, the better."

The route isn't set in stone and planners haven't even had their first official meeting, but officials agree on the basics.

The city plans to lean heavily on existing tracks to which it can acquire the rights. A lone rail line that parallels Holtzclaw would be the north-south backbone for the new service, connecting neighborhoods like Bushtown, Orchard Knob and Avondale.

"Even though you may have just one track, there's a 12-foot right of way on either side of the existing line, so it's pretty easy to add additional capacity and not very expensive," said Ron Harr, president and CEO of the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce. "It's getting the main right of way that costs so much money in other places."

The first phase would stretch from the Chattanooga Choo Choo all the way up to Glass Street, an area local nonprofits have targeted for urban renewal. These high-crime neighborhoods are full of low-income housing, barred windows and vacant store fronts.

Regular rail service could change all that, supporters say.

Lifelong Avondale resident Jay Griffith lives just blocks from the planned rail artery through the center of Chattanooga.

She drives each day to her job at a cleaning service in Eastgate Town Center. But she estimates that half her neighbors don't have access to a car and must rely on CARTA buses.

Buses in her neighborhood are so full at peak times that people stand in the aisles. But the buses don't run everywhere and they don't run all the time.

"A lot of people in this neighborhood don't have a job because they don't have transportation," she said.

She thinks a local rail service could do a lot for people, connecting them to work and play. She predicts many people would ride the train just for the novelty.

"Most people haven't ever rode a train in their life," Griffith said.

TICKETS, PLEASE

Densely populated cities such as Los Angeles, New York and Chicago have long relied on train transport to reduce congestion.

But many U.S. cities turned their backs on rail, evolving into sprawling suburban corridors alongside the developing interstate highways that in 1956 began to suck away passenger and freight traffic from railroads. For long trips, travelers migrated toward air travel, which is subsidized through taxpayer-supported airports.

Those trends are now changing. A wave of smaller cities like Kenosha, Wis.; Oklahoma City; and Kansas City are investing in rail travel as an alternative to sinking money into overcrowded highways and bus systems. Particularly popular now is the rebirth of the urban streetcar, which isn't under consideration in Chattanooga.

Some 50 U.S. cities are planning or already operating light rail and streetcar services. Some of them share a number of similarities with Chattanooga. Doug Bowen, managing editor of the monthly magazine Railway Age, said the rail craze could boost the Scenic City's shot at securing federal funding, despite the city's relatively small size.

"I don't think the size is a critical factor. If anything it might work in your favor," he said.

As the federal government has eased up on regulations on passenger rail,, railroad companies have become more cooperative about letting freight and light rail share the same lines.

"Chattanooga has a lot better chance today, in 2014, in establishing [light rail] than it would have had in 2000 or even 2008," Bowen said.

Getting it done won't be easy. Proposed rail projects spark political battles. People will say Chattanooga isn't big enough, that the city doesn't need light rail service, that it costs too much. Why should everyone have to pay for something that only a few will use?

But that objection ignores the point that all transportation, including driving, is subsidized to some degree, said Bowen, an admitted advocate of passenger rail.

"People will use any and all arguments because, to be fair, it's unfamiliar. You're dealing with two to three generations of people who have forgotten what light rail is," he said. "People in Chattanooga haven't seen a streetcar or a light rail car in generations."

Though Chattanooga's rail system has no shortage of boosters, some experts wonder whether Chattanooga could build its line for the promised $35 million.

"That doesn't seem realistic," said Jeff Brown, a Florida State University professor who researches light rail and other public transit projects.

Brown said many of the cities that are jumping onto light rail and street car projects are decidedly larger than Chattanooga, and benefit from economies of scale.

He's also skeptical that Chattanooga could secure full access to railroad-owned lines. Such arrangements often present scheduling complications and massive expenditures for additional lines.

"It's definitely ambitious for a city that size," Brown said. "My sense is if they're trying to get federal funding for this, they need to have a really compelling argument. What are they thinking this thing will do?"

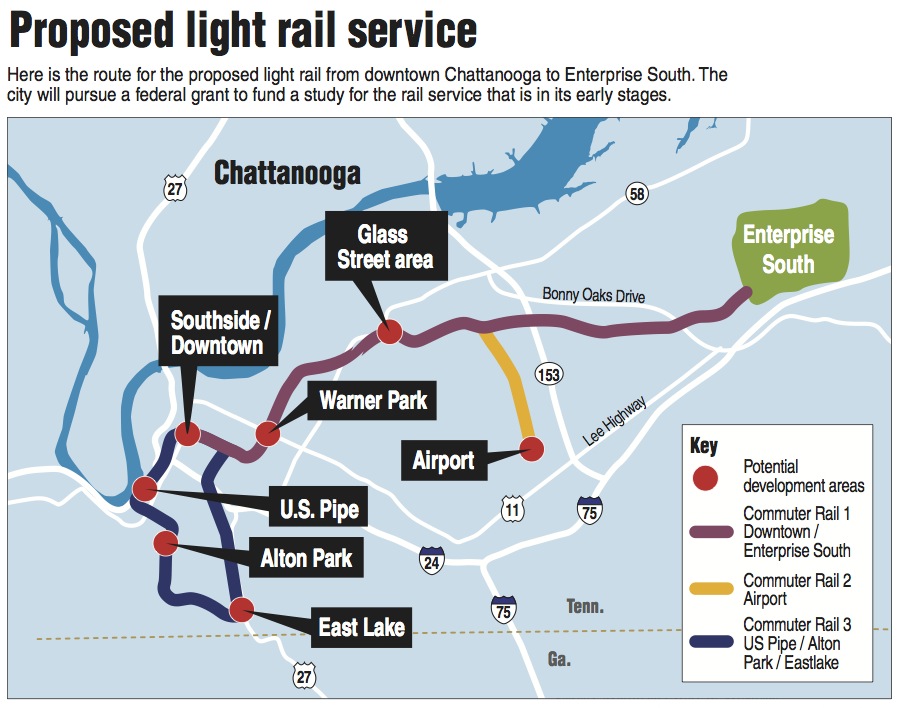

Chattanooga's light rail would initially connect the airport and Enterprise South to the city's Southside, before looping through the U.S. Pipe facility and Alton Park.

But the prohibitive cost of a bridge means there are currently no plans for it to cross the Tennessee River to connect the North shore and Signal Mountain to the rest of the city. Commuters from Georgia will also be left waiting at the station, as the current proposal doesn't slice through Missionary Ridge to reach East Ridge or Fort Oglethorpe.

If Chattanooga gets train service, the location of the stops will be key, Brown said. Failed projects, such as Jacksonville's people mover or Tampa's streetcar, simply didn't offer compelling destinations -- the cardinal sin of train design.

"[They're] not really providing access to places that lots of people want to go," he said. "It fundamentally is a mismatch between the location of the street car or the people mover, and where people actually want to go."

LEAVING THE STATION

The diesel is in the details when it comes to whether Chattanooga's light rail system will steam out of the station or remain stuck on a siding.

If the system can take advantage of the existing rails without building too many bridges or tunnels, the cost of adding rail could add up to just a few million dollars more than the city's $24 million streetlight replacement program

But if the city can't reach favorable deals with Norfolk Southern and CSX, the nationwide companies that own much of the city's rail infrastructure, building the system from scratch could cost much more.

In Minneapolis, federal, state and local agencies spent $715 million to build a 19-station rail system from scratch that connects the airport and the Mall of America to downtown Minneapolis.

Ticket sales cover only about 40 percent of the costs to operate the line, which is being expanded for another $957 million, said John Siqveland, public information officer for the city's metro transit agency.

The whole thing is subsidized by a quarter-cent sales tax.

"Public transportation, like safety or public education, does not turn a profit," Siqveland said.

That is, unless you ask officials in Austin, Texas.

There, officials built a 32-mile, nine-station line that connects the northern suburbs to the center of town. The city spent only $100 million on the whole project, which used federal funding, existing track, diesel locomotives and leased rail cars to save money.

Private development around the stations, much like in Minneapolis, has totaled around $1 billion so far, with more on the way and expansions around the corner. Most important, the rail line is profitable, said John Julitz, public information officer for the Austin metro.

"We're maxed out on capacity, standing-room only," he said. "We did over 750,000 passengers in 2013, and that's a commuter rail service that stops running effectively after 6:30 p.m. during the week and doesn't run on Sundays."

There's just something about trains that people enjoy. Unlike buses, which often have confusing routes, trains are easy for consumers to understand and are perceived as more reliable, said Rick Hitchcock, who was chairman of the CARTA board for 15 years.

"One of the advantages of the rail system is that people can go out and look at it and know where it's going and where it came from," he said. "You can't do that from a bus if you don't understand where the route goes."

DERAILED

Critics doubted that Norfolk, Va., a city not much larger than Chattanooga although much, much denser, could make its light rail project work and questioned the need for such a service.

Like Chattanooga, Norfolk has geography issues. It's hemmed in by bridges, tunnels and waterways. And it's part of a much larger metropolitan area that includes Virginia Beach, Newport News and the world's largest U.S. Navy station.

The city's light rail project, The Tide, opened in 2011 at a cost of about $318 million -- more than half of which came from federal funds.

Despite skeptics, The Tide beat expectations with some 5,000 passengers each weekday. In 2013, the train's ridership reached about 1.8 million, compared to 6.6 million for the city's bus service.

"I think a lot of regions look at light rail as only sustainable for these giant metropolitan areas, but that's really not the case," said Tom Holden, spokesman for the regional transportation agency that operates The Tide. "They're effective in many environments that don't have the density of L.A. or Boston."

Aside from the up-front costs, The Tide costs about $8 million a year to operate. More than half of that is covered by federal dollars. Fares make up for about 13 percent of the overall cost. In the 2013 fiscal year, local taxpayers spent about $2.5 million on the service.

Norfolk's 7.4-mile track makes 11 stops and only operates within the city limits, though officials are eyeing expansions to other municipalities like nearby Virginia Beach.

Chattanooga's proposed light rail would be more than three times longer than Norfolk's existing track, but officials here don't plan on laying all new track as was required in Virginia.

But megaprojects are never easy, said Mike Mallen, a partner in the U.S. Pipe development, which would benefit from a light rail station. Between geography, budgets, environmental impact and eminent domain, every infrastructure project is fraught with obstacles.

"They're not any different than problems any other city has had to confront," Mallen said. "I just think the benefits so far outweigh everything else. It's opportunity and more opportunity. It's not pros and cons, it's pros and more pros."

Contact staff writer Ellis Smith at 423-757-6315 or esmith@timesfreepress.com with tips and documents, or staff writer Kevin Hardy at 423-757-6249 or khardy@timesfreepress.com.

Previous video report on the issue: