Centuries of history and culture are being lost in Syria and Northern Iraq from looting and deliberate, systematic destruction by the Islamic State and other militant groups and warring factions.

The list of vandalized or destroyed sites reads like a tourist's Middle Eastern vacation itinerary: Jonah's Tomb, the Uwais al-Qurani Shrine and the Ammar ibn Yasir Mosque, the Great Umayyad Mosque and other sites all over the ancient city of Aleppo, Dura-Europos, the Sanctuary of Baal, important sites in ancient Palmyra, Krak des Chevaliers near the Syria-Lebanon border and the ancient Syrian Orthodox Church in Tikrit.

What was once scattered plundering by moonlight has evolved into the industrialized rape of history, with dozens of sites added weekly to the losses in Syria's cultural warfare.

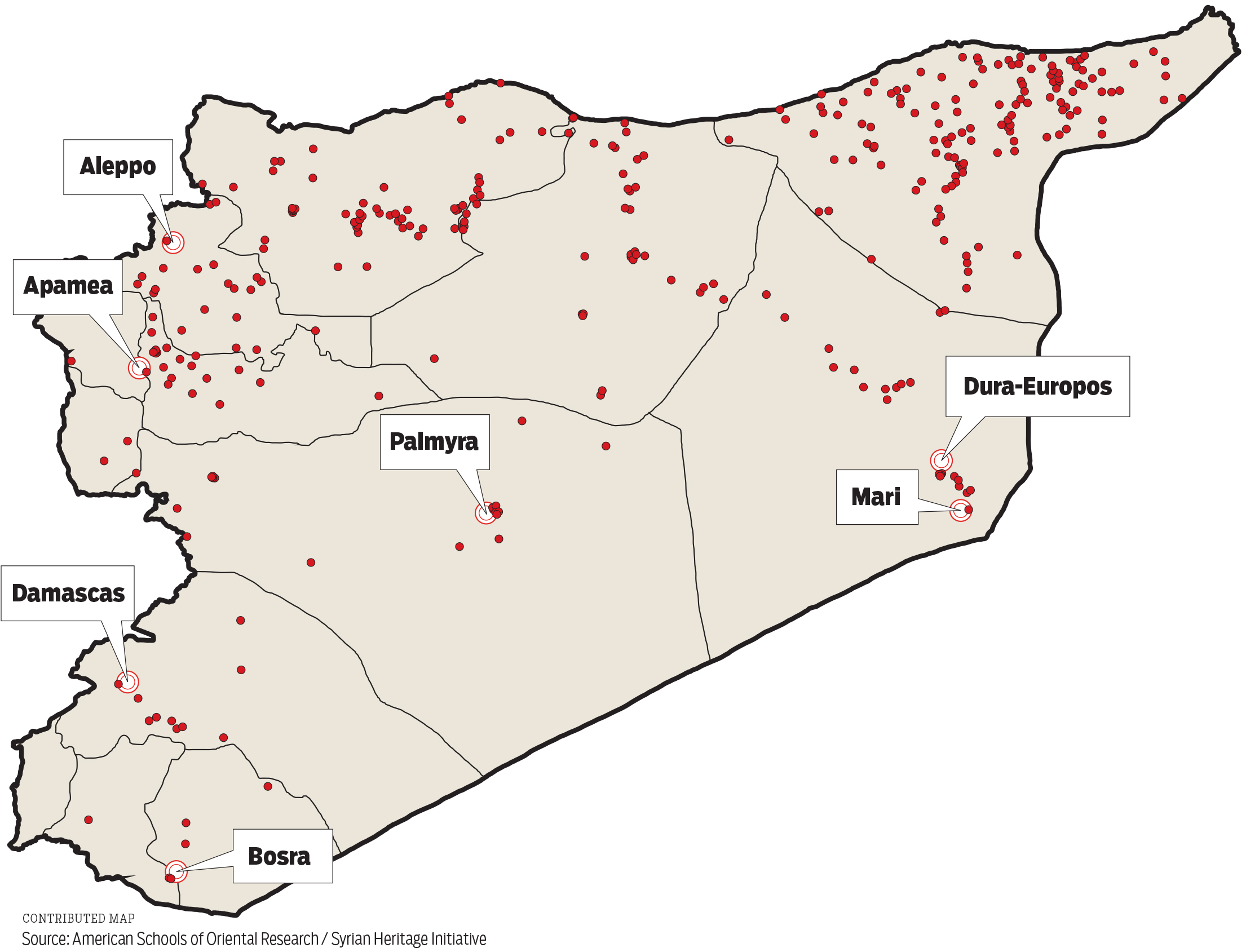

Dr. Andrew G. Vaughn, executive director of the American Schools of Oriental Research and a 1984 graduate of McCallie School, said during a visit to Chattanooga last week that the group's preservation project -- the Syrian Heritage Initiative -- aims to identify and document sites of looting and those in danger of being looted.

The project stems from a cooperative agreement between the schools group and the U.S. Department of State.

State Department spokeswoman Susan Pittman said the partnership will work closely with law enforcement and organizations tracking the growing problem.

A United Nations resolution passed Thursday may help the problem but there's more work to do, Pittman said.

"The resolution contains a legally binding ban on the illicit trade of Syrian antiquities and reaffirms the ban on Iraqi antiquities, and calls upon agencies like UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and Interpol to assist in implementing these bans," Pittman said.

Satellite images show a dramatically changing landscape, with the destruction in some cases on a grand scale involving heavy excavators and bulldozers, Vaughn said.

Majestic domes and spires in some areas are filled with bullet holes or reduced to unrecognizable rubble. Many archeological sites have been wiped out of existence and others are pockmarked with looters' pits, showing where militants pillage a history to sell for weapons and as part of efforts on both sides of the civil war to cleanse the land of cultural and religious reminders of Syria's past.

Even more disturbing, Vaughn said, looters are pilfering artifacts from sites that have never been studied. Looted artifacts are flooding the black market, particularly in Turkey.

In order to stop the black market avalanche of Syrian relics, "anything we do in the Middle East needs to be a broad-based effort and needs to be seen by the people in those countries as the whole world responding, not just the United States," Vaughn said.

Erasing history

Signal Mountain resident Dr. B.W. Ruffner, American Schools of Oriental Research board chairman and a physician who lived in the Middle East as a child, said the losses to human history are incalculable because Syria contains many of the world's best archeological sites.

"The Euphrates Valley from Iraq up to Turkey is really the birthplace of civilization going back 5,000 or 6,000 years," he said. "That's the area that ISIS has concentrated on. Under their control now there are just countless priceless sites."

Ruffner's fascination with Middle Eastern history and culture is lifelong and stems from his childhood, when his father was assigned to Beirut, Lebanon, in his job with the State Department.

"When I was a kid, we all jumped in the car and explored these sites. If it wasn't at least a thousand years old, we weren't interested in it," recalled Ruffner, 75. "An excitement about the past was bred into me at an early age."

According to officials, a recent study by Ricky St. Hilaire found that imports of Syrian antiquities in the U.S. rose 133 percent between 2012 and 2013 and Iraqi antiquities imports rose 672 percent over the same period.

"We're only seeing a small fraction of huge masses of stolen material," Michael Danti, the schools group's director of cultural heritage communications, told attendees of the organization's Syrian Heritage Initiative Symposium in San Diego, in November. "Much of it will never reach public marketplaces and will go directly to private collections."

As a result, two of the largest and most lucrative areas of Syrian employment are in the oil market and antiquities looting, Danti said.

Documenting danger

On Thursday, Danti said the group is receiving frequent damage reports from Syrians who risk their lives working undercover to document what's lost or damaged, and trying to protect what escapes militants' notice, he said.

Extremists' primary targets are mosques, tombs, shrines and churches that they see as "inappropriate to their version of Islam," Danti said. "These groups, like Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra, are trying to stamp out cultural diversity and impose a single version of Islam on everyone."

Looting is now on an industrial scale, he said.

"They are very rapidly destroying large archeological sites from a number of different time periods," he said.

Syria is famous for "firsts" when it comes to ancient civilizations and some of the earliest writings. Mosaics, sculpture, coins from the Classical era and early Christian relics from the Byzantine period are being lost at an alarming rate, Danti said.

"On top of the combat damage and the deliberate destruction and the looting, you also have unbridled development," Danti said. "People are now building houses on archeological sites and we've got displaced populations all over Syria -- millions of people -- who have lost their homes and had to flee from major cities who are living in standing sites."

The "dead cities" of northwestern Syria are becoming living quarters, while other archeological sites are being plowed and planted for agricultural purposes, he said.

Aleppo, a well-preserved old city in the north of Syria that has drawn visitors for hundreds of years, is one of the worst-hit sites, and weekly reports paint an increasingly bleaker picture.

"It was an incredible location with markets and mosques, churches and shrines, and that's just being annihilated because it's the center of combat between opposition forces, extremists and the Syrian regime," he said.

"One of the most destructive practices that I've been documenting now for the last year is the use of what we call 'tunnel bombs,'" Danti said.

To root out Syrian regime forces from Aleppo, extremists forces "dig long, deep tunnels under historic buildings, fill them full of fertilizer and they'll detonate these massive explosions to destroy huge areas of historic remains."

The regime responds with helicopters that drop 55-gallon "barrel bombs" filled with explosives onto buildings, he said.

The back-and-forth violence is making Aleppo "look like the surface of the moon," Danti said. "It's really heartbreaking; it's being ground into dust. Every time we get new satellite imagery, there's new damage."

For successful rescue of Syria's cultural sites, the humanitarian crisis in Syria must be solved first, he said, and work must be done to keep the crisis from spreading much more into northern Iraq.

The school group's director of geospatial initiatives, Scott Branting, uses satellite images and global positioning satellite locations to track the destruction.

"Definitely the Islamic State and some of the other radical groups turn toward purposeful destruction on a large scale and for a large media audience. That is something that has changed from the past," he said.

Social media has created a venue for publicizing destruction and puts smaller archeological sites in jeopardy, he said.

Contact staff writer Ben Benton at bbenton@times freepress.com or twitter.com/BenBenton or www.facebook.com/ben.benton1 or 423-757-6569.