TRENTON, Ga. - As controversies brew around them, the leaders of Trenton, Ga., believe their city will be spared complaints about the Confederate flag.

Here, where local lore says their ancestors were itching to fight the North so feverishly that they withdrew from the Union before the rest of the state, they believe the hoopla out of Atlanta, Nashville, South Carolina and Alabama will miss them.

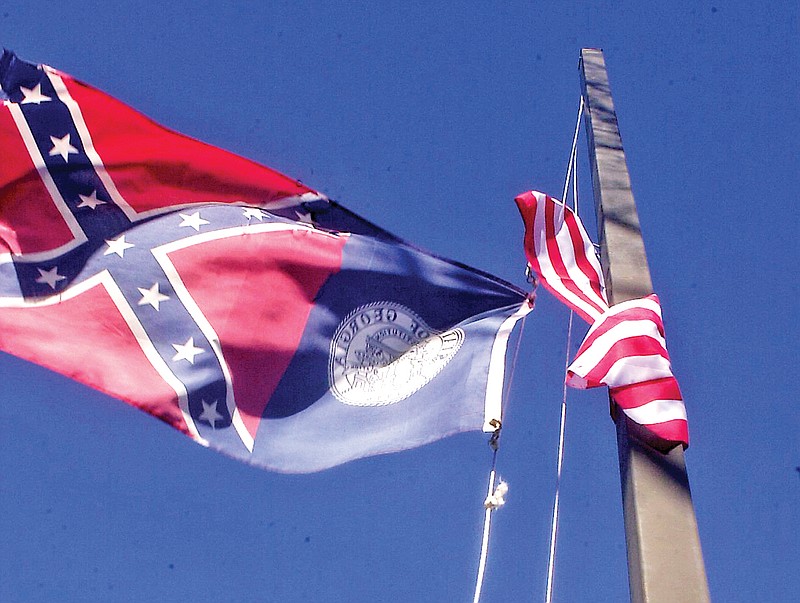

The Confederate controversy came here once before, back in 2001, when the commissioners voted to adopt an official city flag. They chose Georgia's old flag, the one dating from 1956 and bearing a Confederate battle emblem next to the state seal, that the state Legislature voted to take down months earlier.

The Associated Press spread the story throughout the country, and film students from the University of California at Berkeley shot a documentary.

Today, some commissioners said the flag is a non-issue. Sandra Gray and Tommy Lawson said the flag isn't even flying.

But members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans said the flag still flies above Trenton, a Dade County city of 2,000 whose black population is about 3 percent. A city clerk confirmed the town still uses the old Georgia flag, but it's not flying right now because wind and rain tattered their old flag and the replacement hasn't arrived.

Told Wednesday that the city still uses the flag, Lowery said, "I don't really have any preference one way or the other."

Gray said she didn't pay attention to the flags in front of city hall, though she prefers to stick with just one: "I'm an American. Go with the American flag all the way."

National response

After a 21-year-old white man was charged with the June 17 massacre of nine black worshippers inside a Charleston, S.C., church, politicians throughout the Southeast have called for their states to permanently remove signs of the confederacy from their capitols.

On Monday, South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley said the state legislators should vote to remove the Confederate battle flag. On Tuesday, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam said he favors removing a bust of Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a founder of the Ku Klux Klan.

On Wednesday, Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley ordered the removal of the battle flag.

Spokespeople for Sears, Walmart and Amazon, meanwhile, said earlier this week their stores will remove items with the battle flag on them. Warner Bros. representatives added that they will remove the Confederate emblem from replications of the "General Lee," the iconic "Dukes of Hazzard" Dodge Charger.

John Deffenbaugh, the state representative from Dade County, said Trenton officials should decide for themselves whether to keep flying the flag. He worries that outside pressures could go too far; that many more signs of Southern heritage will be removed because of allegations of racism.

"I'm not for or against the flag," he said.

But Dr. Francys Johnson, president of the Georgia NAACP, said no city should fly the state's former flag.

"It is past time to take down these relics of hate and these symbols of fear," he said. "They have no place in the modern society."

A spokesman for U.S. Rep. Tom Graves did not return an email seeking comment Wednesday.

The city flag - the old Georgia flag with "Trenton, incorporated 1854" stitched on it - first flew in 2002, a year after the commissioners voted for it. Anthony Emanuel, who became mayor in 2004, then took it down.

But his predecessor objected, and Emanuel held a straw poll. In November 2005, 64 people said they were against the flag. Two-hundred and seventy-eight said they were for it.

"We'll put it up," Emanuel said then. He is out of town this week and did not return an email seeking comment.

Freddie Parris, a member of the Dade County chapter of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, said the flag should continue to fly. He said critics have turned the battle flag into a scapegoat.

"You can't sit there and say a flag caused this," he said. "It's just popular for now with elections coming up and all the political correctness. The flag has nothing to do with it. The (Charleston shooter) was just an idiot and a racist."

The State of Dade

Parris said the people of Trenton support the old Georgia flag because it is a sign of their heritage. Their ancestors are the ones who pulled out of the Union even while the rest of Georgia's leaders debated the issue.

The State of Dade, they called themselves.

The story goes that in 1860, during a state Senate debate about whether to secede, the representative from Dade County stood up in the back of the room.

"By the gods, gentlemen," "Uncle" Bob Tatum said, "if Georgia does not vote to secede immediately from the Union, Dade County will secede from the state and become the independent state of Dade."

Tatum then stormed out of the room. Impatient, he rode home and told his delegation that the other politicians were waffling. Tatum then sent a proclamation to Washington: The people of Dade County had seceded on their own.

The county stayed independent until July 4, 1945, when 4,000 people packed into Trenton for a celebration. The county officials asked the crowd if they wanted to rejoin the Union.

"Yes!" they said, according to newspaper accounts.

Then the members of the crowd let out a rebel yell, and the county received a telegram from President Harry S. Truman.

"Welcome home, pilgrims," Truman wrote.

Problem is, that famous local legend isn't true, at least not the part about seceding early. The party happened in 1945 and The New York Times covered it. But the event was promotional, like a tourism advertisement.

The part about Tatum? University of Georgia history professor E. Merton Coulter wrote in 1957 the tale was a myth, spread by word of mouth. Elderly residents told Coulter that, as far back as the 1870s, people in Dade County were talking about Tatum's Senate chamber outburst.

But, Coulter wrote, Tatum was a state representative, not a senator. And if he ever made a passionate speech in the chamber about secession, there isn't a record of it. He wouldn't even have needed to: The state legislators overwhelmingly voted to organize a special convention to decide whether to secede.

Dade County chose two representatives to that convention, and Tatum wasn't named. And when the majority of representatives voted to secede, the Dade County representatives actually said no.

The county's representatives wanted to stay with the Union.

So why the myth about leaving early? Coulter said this was a sign of Southern pride after the devastating Civil War. He wrote that Jones County, Miss., and Franklin County, Tenn., circulated similar legends.

Coulter speculated that this was a sign of insecurity.

"Because of her isolation," he wrote, "Dade had come to be looked upon as different - sometimes humorously so."

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at tjett@timesfreepress.com or at 423-757-6476.