Raw leather sat on John White's table Tuesday, but he couldn't convince himself to work.

The leather could mean money, he told himself. He could form it into a belt, a pocketbook, a keychain -- the product of a skill he learned during his 22 1/2 years in prison. But what's the point?

If he makes an accessory, he will have to sell it. That means talking to strangers. He doesn't trust strangers. Strangers are the reason he went to prison, the reason he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

"I lose," he said. "I always lose."

In 1979, a jury convicted White of rape. In 2007, state officials exonerated him, realizing that DNA evidence matched one of his former high school classmates.

White, 54, now lives in a nice, four-bedroom home in Manchester, Ga. But he still feels incarcerated. He doesn't know how to live without someone else's orders. Life in prison was so much easier, he said.

Still, he's glad he's exonerated. Not because he missed freedom but because of the plain truth: He was always innocent and he wanted people to believe him.

In his case, he said, prosecutors relied on the fact that the victim, a 74-year-old woman, identified him in a lineup. It didn't matter that the room was dark during the crime, or that the victim was not wearing her prescription glasses.

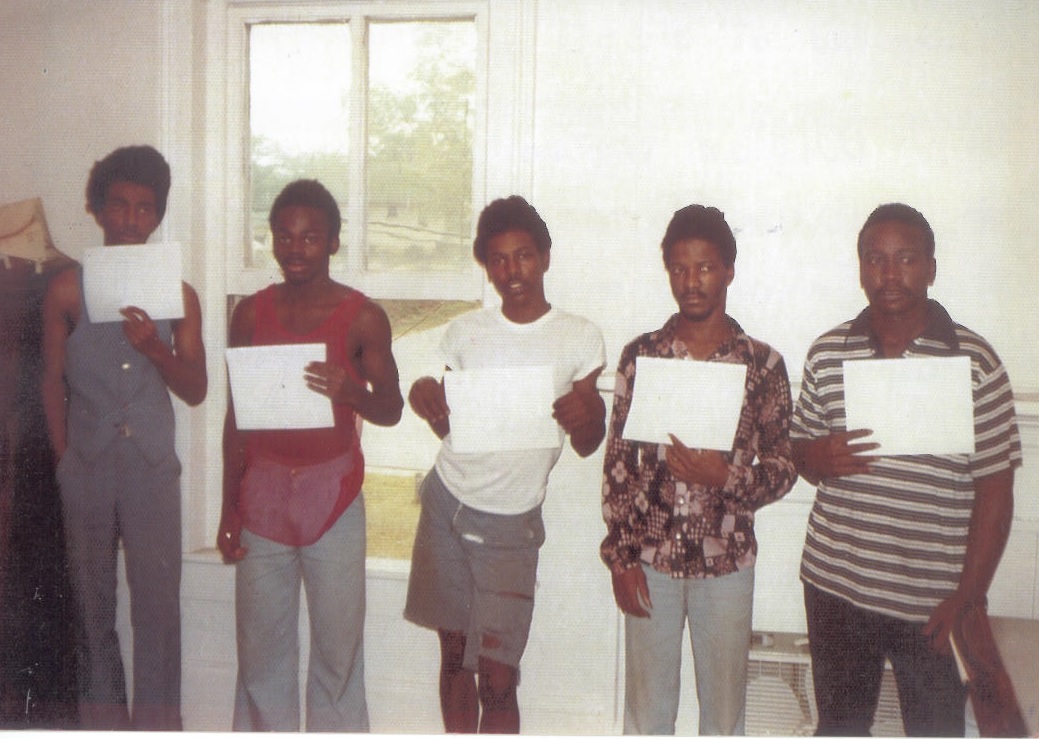

James Parham, the man whose DNA matched the pubic hairs found at the crime scene, stood in that same lineup, a couple of feet to White's left.

That's why White lobbied this year with the Georgia Innocence Project for a bill mandating that state police agencies have written policies aimed at reducing the likelihood a witness will falsely identify someone as a criminal.

The Innocence Project is a nonprofit legal organization that uses DNA evidence to exonerate defendants such as White.

On April 2, the Georgia Senate and House of Representatives both passed the bill, and Gov. Nathan Deal signed it into law two weeks ago.

Under the new law, the police official conducting the lineup with the witness must be someone who doesn't actually know who the suspect is, so he or she doesn't subconsciously suggest a person in the lineup.

In a live lineup, police should use four "fillers," people who look similar to the witness' original description of the criminal. In a photo lineup, police should use five "fillers."

Police should tell the witness that the criminal isn't necessarily in the lineup so the witness does not feel like he or she has to pick somebody. If the witness does identify the suspect, police should ask the witness how confident he or she is, so the jury can decide if that identification is credible.

The law does not force police to follow these rules, said Aimee Maxwell, executive director of the Georgia Innocence Project. But defense attorneys will point out when the policies aren't followed, undercutting an investigation, she said.

"You're going to have to explain that to the jury," she said. "These days, I don't think the average citizen is OK with police officers not following the law."

Frank Rotondo, executive director of the Georgia Association of Chiefs of Police, supported the bill.

"Nobody wants to convict the wrong person," he said. "Why continue to stand on old methods and principles?"

Rotondo said investigators leaned on witness identification decades ago, before studies showed how unreliable they were, because DNA evidence was not as available. In the 1980s, he said, police officers rarely tried to examine DNA unless they were investigating a slaying.

Few crime labs could process that evidence. And it was expensive. And they had to have gathered blood or saliva.

Now, examining DNA is easier and cheaper. And investigators can find smaller fragments, such as fingerprint oil or a hair follicle.

The bill's sponsor, Sen. Charlie Bethel, R-Dalton, said the main accomplishment here is to create "statutory framework." If a police officer doesn't follow these rules, a judge or a defense attorney can point out the error with a state law on the books.

Bethel believes it won't change most investigations, though.

"This is what's being done in the overwhelming majority of law enforcement agencies in Georgia," he said. "It's clearly accepted. ... The overwhelming majority of law enforcement officers, this will not represent any meaningful change."

Maxwell said that's not true. After filing an open records request for the policies of every police agency in the state, she found that 76 percent do not require that the administrator be "blind" to who the suspect is, 67 percent do not tell the witness that the suspect might not be in the lineup, and 63 percent don't get a "confidence" statement from the police, she said.

Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk said he supports these changes.

He doesn't yet have the rules as policies for his officers, but he said administrators have been telling investigators to follow these suggestions for about a year now, ever since they learned in a statewide training that the changes might be coming though the Legislature.

"It's just reassuring," he said. "We need to show that nothing is done that can be construed as showing favoritism."

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at tjett@timesfreepress.com or at 423-757-6476.