On the third floor of Criminal Court, behind a sturdy brown door, inside a dimly lit room and away from the Monday morning chill, Elaine Kelly delivers an ultimatum.

"You want us to let you go home to an environment that you already told us is unsafe; where there's crack?" she asks her client.

The man, one of roughly 100 clients participating in the Hamilton County Drug Court program, tells Kelly his landlord has been helping him clear out the negative influences.

It's a safe place, he insists.

"All right," Kelly replies. "Then I'm going to send narcotics over."

It's 9:45 a.m. in Drug Court.

Since 2005, Drug Court has provided a haven for addicts who want to get clean and avoid the prison cycle. But when its co-founder, former Criminal Court Judge Rebecca Stern, retired in June, many wondered who would fill the void.

When he was appointed last month to the bench, Judge Tom Greenholtz promised to make Drug Court a priority. More than anything, he appears to be at the helm of a makeover.

Next month, Drug Court celebrates its 10-year anniversary. According to Kelly, the program's coordinator, more people are participating. And, to increase the public's awareness about addiction, Greenholtz announced an widespread plan to extol the values of a drug court system, one that champions rehabilitation over incarceration.

"I'm going to go into the churches, the schools, the community centers, and I'm going to talk about what happens here," Greenholtz said last month.

But behind the doors of Drug Court lie heavy moments that pass quietly.

"That was easy," Kelly said Monday morning after her client left the room. "When you have a women who's been molested since the age of 8 who turns to prostitution and doesn't know how to break the cycle and sits there and cries? That's harder."

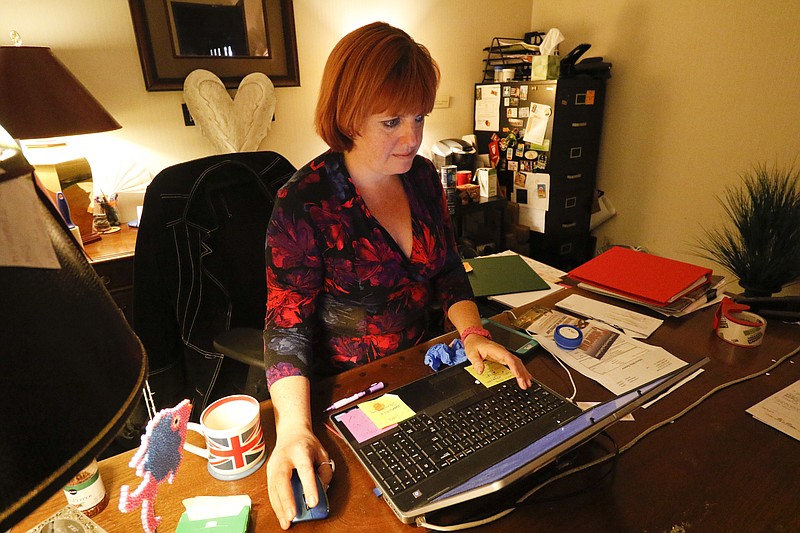

Born in Britain, Kelly worked in a Catholic bookstore and wanted to be a nun until she turned 18. Then she went to Philadelphia, worked at a summer camp and decided to study educational psychology. Before co-founding Drug Court, she did trial consulting for a private practice in Chattanooga.

People float in and out of her office, taking 100-milliliter urine sample cups, making small talk, getting scolded if they broke from their plan. Kelly scrolls through the 58-page docket, noting the clients who displayed good attitudes. It's 11:13 a.m. in Drug Court.

During lunch, Kelly and one of her case managers, Jeff Hill, consult with an assistant district attorney; a representative from the Council for Alcohol & Drug Abuse Services; and a parole official to discuss their clients, some of whom are dealing with substantial difficulties.

In court, Greenholtz recognized at least five people for their great attitudes and strong improvement. But he also had to dismiss one client for sneaking medication into her treatment room and lying about it.

"One of the parts about the Drug Court that I like the least is having to tell someone that they're no longer part of the program," Greenholtz said to the woman. "And I'm going to have to unfortunately tell that to you. The staff has voted unanimously."

A police officer led the woman into the back hallway. It's 2:26 p.m. in Drug Court.

To better understand everyone who passes through the program, Greenholtz reserves time for questions and comments such as, "What's your child's name?" "How long have you been working at Subway?" "My wife loves Italian food, I'll have to visit your restaurant sometime."

When court is finished, Kelly ties up loose ends with the clients. For the rest of the week, she'll coordinate daily drug screenings and work on transitioning people into the program - if there's an available treatment center bed.

"I'll get home eventually," she says.

It's 4 p.m. and Drug Court is only just beginning.

Contact Zack Peterson at 423-757-6347 or zpeterson@timesfree press.com. Follow @zackpeterson918.