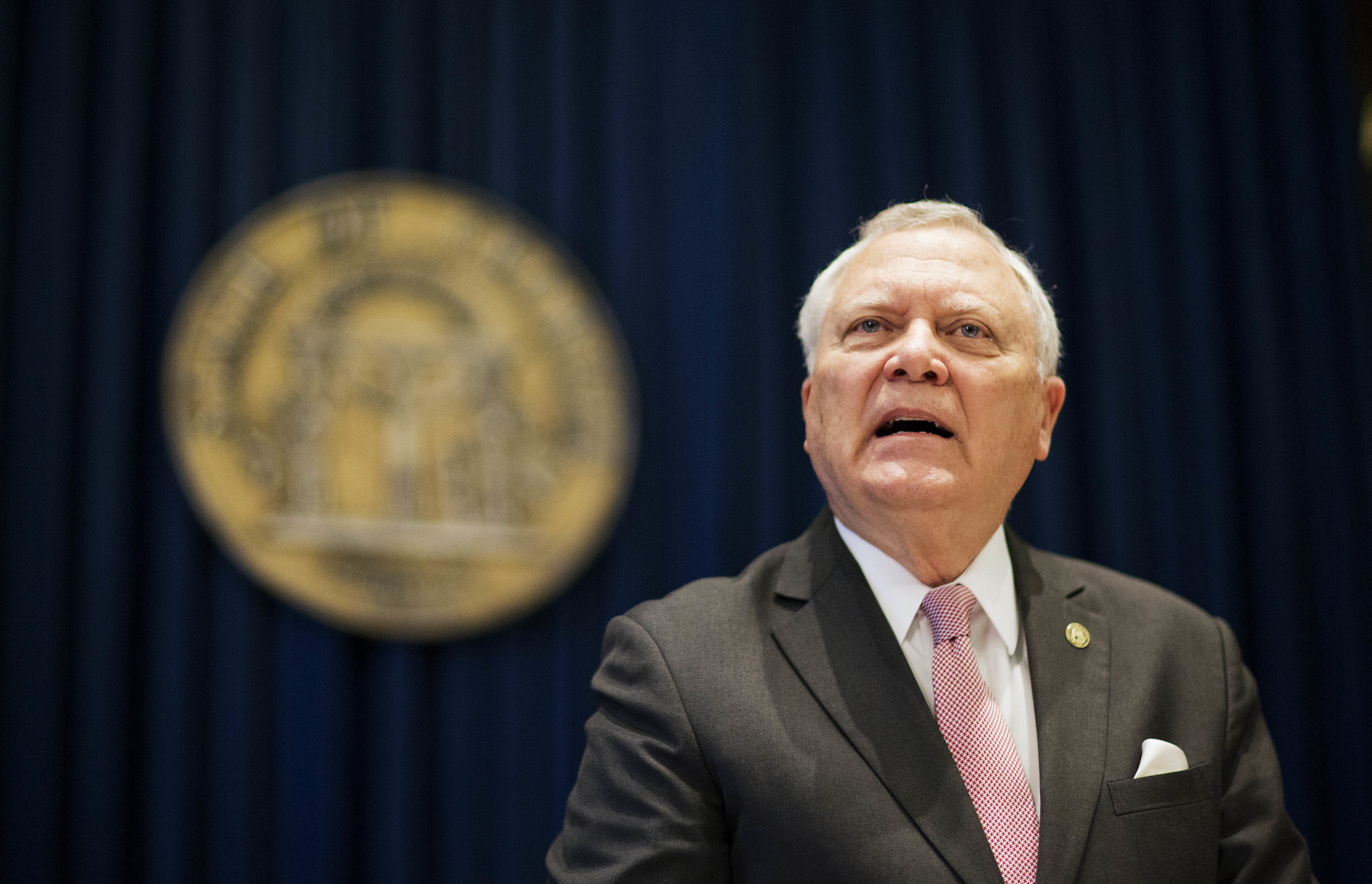

FILE - In this March 28, 2016 file photo, Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal speaks during a news conference in Atlanta. Tuesday, Nov. 8 presidential results and Georgians’ rejection of a proposed amendment to the state constitution are already having an effect on the upcoming legislative session. Health care and education issues were expected to dominate 2017 at the Capitol. But key policymakers say discussions about expanding Medicaid in Georgia are likely on hold. Deal says he’s mulling options after voters rejected allowing a state takeover of some schools. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

FILE - In this March 28, 2016 file photo, Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal speaks during a news conference in Atlanta. Tuesday, Nov. 8 presidential results and Georgians’ rejection of a proposed amendment to the state constitution are already having an effect on the upcoming legislative session. Health care and education issues were expected to dominate 2017 at the Capitol. But key policymakers say discussions about expanding Medicaid in Georgia are likely on hold. Deal says he’s mulling options after voters rejected allowing a state takeover of some schools. (AP Photo/David Goldman) For years, Georgia's governor has championed a program to help drug addicts recover.

And for years, a North Georgia judge stood in defiance of the idea, one of the last holdouts in the state. But that judge, Jon "Bo" Wood, retired two months ago. And with his departure, local law enforcement and courthouse leaders promise a change is coming.

Judge Kristina Cook Graham, who replaced Wood as the chief judge in the Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit, said she hopes to bring a drug court to the region by summer 2018. Local officials will spend next year figuring out how to launch the operation, learning how many employees they need and how much outside funding they can get.

"We're trying to do it to help people and better the citizens that are going through the justice system," said Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk, who pushed years ago for a drug court, only to be rebuffed by Wood. "The process we have now isn't really getting it done."

Drug courts aren't new. Whitfield County launched one in 2002. Hamilton County's opened in 2004.

But since he took office five years ago, Gov. Nathan Deal has boosted state funding for such courts by about 750 percent, from $2.7 million in 2012 to $23 million this year.

Deal's own son has been a drug court judge since before the Republican governor took office, and Deal believes these programs stop repeat offenders.

He hasn't pushed just for drug courts. The state money goes toward any "accountability court" programs for military veterans who get in trouble, people with mental illnesses and people arrested for DUI.

The Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit (which covers Catoosa, Chattooga, Dade and Walker counties) is one of only two judicial circuits in the state that don't have accountability courts.

The increased funding for these programs is a key piece of Deal's law enforcement policy, which has drawn praise from progressives throughout the country.

"One could reasonably argue that Georgia is doing more to reform its criminal justice system than any other state in the country," Naomi Shavin wrote in The New Republic last year.

In drug court, people facing charges have a choice: Go to jail, or get treatment. This applies not only to drug charges but also to crimes that stem from drug use, like theft or forgery. The only catch? A defendant can't have a history of violent crime.

Offenders who sign up have to go to therapy and classes about addiction. They also have to hold down jobs. And they are subject to drug testing every day, with failed tests leading to some form of punishment.

The judge gets progress reports on each defendant, and can praise them for good work, give them warnings or send them to jail, depending on what they did that week.

It usually takes about two years before people who successfully complete the program "graduate" from drug court.

State officials believe accountability programs really work. The Georgia Council of Criminal Justice Reform, with members appointed by Deal, boasted about these figures:The number of prison commitments dropped from 21,700 in 2009 to 18,100 in 2015.

Forty-two percent of people in state prisons were nonviolent offenders in January 2009, compared to 33 percent in December 2015.

The state prison population was at 51,800 in December 2015, down from 54,900 in July 2012.

Local resistance

Locally, an effort to launch a drug court began after Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk took office in 2012. He met with some legal officials to discuss how to make a program work here. District Attorney Herbert "Buzz" Franklin was on board. So was Public Defender David Dunn.

But Wood was a critic, said Dunn, Sisk, Graham and Judge Ralph Van Pelt Jr. Because Wood was the chief judge in the circuit, the group couldn't apply for outside funding from the state or federal governments.

Wood, who retired Sept. 30, did not return calls seeking comment for this story. But multiple sources said Wood felt accountability court judges acted like social workers. He didn't believe that was a judge's place.

Van Pelt said the position can, in fact, put judges in an awkward position if they don't follow proper training. Case in point: Amanda Williams.

Williams oversaw Georgia's largest drug court in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. About six years ago, some attorneys complained she jailed drug court defendants for indefinite periods when she believed they broke the rules. Sometimes she denied jailed defendants access to lawyers.

In 2011 the public radio show "This American Life" featured Williams, spotlighting the case of Lindsey Dills. A drug court defendant, Dills spent 73 days in solitary confinement and attempted suicide. According to The Associated Press, Williams did not control the status of Dills' confinement when she went to jail. But she did order that Dills be held without the ability to make phone calls, see visitors or receive mail.

In January 2012, after a Georgia Judicial Qualifications Commission investigation, the judge resigned.

"Amanda Williams would be the poster child for a badly run drug court," said Dunn, the Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit's public defender. "There is no question."

Success

Judge Jack Partain, of Whitfield and Murray counties, actually learned how to start a drug court in 2001 from Williams at a conference. After he learned the basics of how it functions, he was on board.

Partain, a Superior Court judge since 1995, was seeing the same people hauled up on drug charges over and over again.

"There was a need for something different," he said. "We had just been taking even minor drug offenders and putting them in prison. They didn't get any kind of therapy or rehabilitation in prison. They get out and they're still addicts."

In Whitfield and Murray counties, about 85 defendants are in the drug court system at any time. New members report to a treatment center at 7:30 a.m. five days per week. They stay for three hours, attending counseling and classes on addiction. They may be tested for drugs.

Treatment center workers may try to help defendants without high school diplomas study for their GEDs. Those in the system are also expected to keep a job.

Don Hoffmeyer, coordinator for Whitfield and Murray counties' drug court, said defendants have to ask permission to change even basic parts of their lives, such as where they are working or who they are dating. He said relationships can be distracting for addicts who have just started recovering.

Court officials monitor offenders, with praise for progress. Those who flunk out may go to jail, boot camp, a probationary detention center or a regional substance abuse treatment center, where they can stay for nine months.

Partain, who is retiring in December, said drug court was one of the most effective parts of his job. He said the "social worker" criticism is inaccurate: He still punishes people - he just does it in a parental way.

"Addicts, they need a little coercion," he said. "What we call a 'nudge from the judge' to make it work. Some of them need consequences hanging over their heads in order for them to strengthen up and do what they need to do and get clean and sober."

Bringing it here

The long-term effectiveness of drug court is difficult to measure. Hoffmeyer said his office does not track recidivism rates for Whitfield and Murray counties because it's hard to keep track of all the court's graduates. For example, if a defendant is convicted of a crime outside Georgia, Hoffmeyer probably won't hear about it.

He said state officials are trying to improve tracking, with the Department of Corrections launching a statewide database of each person assigned to an accountability court. The data on that project is not in yet.

Still, the Council of Criminal Justice Reform argues that the accountability courts have played an important role in reducing the number of repeat offenders. Recidivism rates that hovered around 30 percent for a decade dropped to 26.4 percent last year, according to the council's report earlier this year.

Partain isn't sure how many people he's kept out of jail with drug court, nor does he know how much money this has saved the counties. He prefers a softer analysis, with stories of graduates who he has gotten to know. He believes the program helps people clean up their lives, launch careers and take care of their families.

In Catoosa County, Sisk also isn't sure how the program will affect the budget. He recently said about half of the 200 people in his jail were there for violating probation.

He wondered how many of those people would be helped by a drug court program that takes a hands-on approach to their addiction rather than a cycle of recidivism where their problems build and nobody gets better.

"Whatever job they had, they lost it," Sisk said. "If they're renting somewhere, they're evicted. How much more can you beat somebody down?"

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at 423-757-6476 or tjett@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @LetsJett.