Photo Gallery

How a Hamilton County judge is trying to accomodate victims with a new scheduling order

Parking cost $6 at the Hamilton County Courthouse when three men were charged in 2012 with killing Danny LeCroy's son.

Over the next four years, LeCroy and his family spent $400 to sit in that place, thinking a trial was going to happen, only to learn it was passed to another day by prosecutors who were too busy to tell them beforehand.

Amy Smartt's family was chided for sitting incorrectly in the gallery while her daughter's killer, Taylor Satterfield, celebrated a lesser sentence in court after a jury returned its verdict in July 2016.

And Satedra Smith has been in no-man's land in court since her 20-year-old son, Jordan Clark, was gunned down in August 2015. Her victim advocate can't tell her any more than when the next court date for her son's alleged killer will be. Prosecutors don't want to leak any facts and jeopardize the case. And the lead detective who investigated her son's shooting is on a different case now.

LeCroy, Smartt, Smith and several others say they have spent months tracking cases against the people charged with killing their loved ones, but they often feel left out of a criminal justice process they say champions defendants' rights but is indifferent to victims of violent crime.

For 20 years, victims in Tennessee have had the right to confer with a prosecutor about their case, be informed of all court proceedings, and be heard in court during relevant moments such as sentencing hearings. But, over and over, cases come up on the docket with nothing new to report and are passed several hours later by an attorney. Family members waiting in the gallery grow increasingly frustrated at being told to return another day.

But one powerful ally has taken note of these frustrations and introduced a new way to schedule cases in Hamilton County Criminal Court so witnesses, victims and family members don't have to return to the gallery again and again.

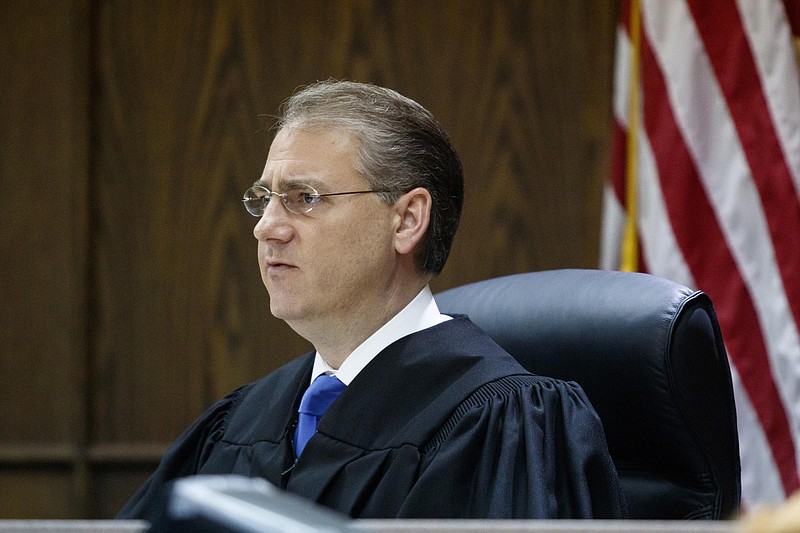

Judge Tom Greenholtz's new, speedier version of a "rocket docket" started the first week of December after a year of observation from the bench.

"When I came over, it became really apparent that people will sit in the gallery all morning long, and from their perspective, nothing is happening," Greenholtz, who was appointed in September 2015, said in a recent interview.

What's actually happening is defense attorneys and prosecutors are exchanging information on cases that will be heard that day. Maybe a crime lab returned forensic evidence in a murder case, and the defense wants to arrange a hearing to suppress it. Perhaps a witness died or moved to another state and the prosecution has to re-evaluate the strength of its case.

Greenholtz's scheduling order creates a series of deadlines during a defendant's first appearance, for motions, evidence disputes, and checkup days. After that, defendants stay off the docket for about three months while attorneys complete the work before each date. Defendants can jump back on the docket anytime to address a legitimate concern, Greenholtz said.

But not to appear for the sake of nothing.

"We have the state's interest. We have the defendant's interests of due process. But we also have other interests," Greenholtz said. "Police officers, family members, victims, witnesses. And the system doesn't send that weight to them. It's subordinated to the others. And that is frustrating to me."

***

Criminal cases typically start in Hamilton County General Sessions Court after law enforcement makes an arrest.

A judge there must decide if there's enough evidence to send the charges to a grand jury. If indicted, a person faces formal charges in Criminal Court and attorneys start the grueling work of processing evidence, forming counter-arguments and working toward a plea agreement or a trial.

Any number of factors can snag a case: A witness dies, the defendant fires his attorney or demands a new one, the prosecutors are waiting on evidence to return from a backlogged crime lab and have 10 other cases.

When officers responded to 1211 Johnston Terrace on Sept. 9, 2010, and found Chance LeCroy dead in his bedroom, their investigation led them to Patrick Carmody, Billy Bob Partin and Ronald Pittman.

But the arrests didn't happen until June 5, 2012, because authorities needed to corroborate their theory that Carmody and Partin beat and shot Chance LeCroy while Pittman held a gun to his roommate's head in the living room.

The nearly two-year wait crushed Danny LeCroy and his family members, who said the lead detective stopped returning their calls a few months into the investigation.

"The breaking point was when Sgt. Tim Chapin at the Chattanooga Police Department died [on April 2, 2011]," said Terri Gizzard, Chance LeCroy's aunt. "The lead detective was pulled off our case to investigate that."

Once in court, the LeCroy family felt like their interests were cast aside.

Pittman convinced a judge to lower his $1.5 million bond to $100,000 and went on house arrest. Carmody's attorney asked for a separate trial from Partin, slowing proceedings in 2013. A judge rejected the request, and the issue went away altogether when prosecutors offered Partin 20 years in prison on a lesser charge of second-degree murder. He accepted in July 2014.

All the while, the family went from one prosecutor to another. They showed up for four trial dates for Carmody. All of them were canceled, but the LeCroy family says no one told them.

"All four times, nobody was there. [District Attorney Neal] Pinkston was never there. No cops. And we'd be down there, expecting trial," Danny LeCroy said.

Grizzard added, "Everybody knew it'd been canceled but us."

Throughout, LeCroy was dealing with cancer, spinal stenosis and radiation therapy, and Grizzard needed prescribed medication to fall asleep at night.

The siblings couldn't understand why authorities seemed apathetic about a 21-year-old whose life touched so many people. On the first anniversary of his death, 40 people signed balloons for Chance and let them go into the night sky. His face became the backdrop on one girl's screen-saver. To this day, supporters gather on his birthday at Buffalo Wild Wings to celebrate Chance with Monster energy drinks.

The district attorney has no control over issues such as judges passing court dates, canceled trials, or the parking garage rates, said spokeswoman Melydia Clewell.

"It is true that on one occasion we were unable to notify some of the LeCroy family of a court date change," Clewell wrote in an email. "That's because Mr. LeCroy changed his phone number without giving us his new number. We have maintained an excellent relationship and open lines of communication with" Grizzard and Chance LeCroy's girlfriend.

LeCroy says he never changed his phone number and that nobody called his sister either. Clewell added any miscommunication was due to Danny LeCroy's "verbally abusive tirades" against prosecutors, police officers and other state employees involved in his son's case.

LeCroy said he never threatened anyone.

"The only thing was when [a police officer] jumped up in my face after I said, 'I'll get Pinkston back when he's up for re-election,' one day in court.

"I aggravated them, I guess, because I wanted something done. I know there were four trial dates set in the last two years before they ever went to trial for Carmody. And we'd go down there and there wouldn't be an officer, nothing. The point remains: There was no respect from the day police came here forward."

Jurors found Carmody guilty of first-degree murder in May 2016 and he is now serving a life sentence in the Tennessee Department of Correction. Pittman, on the other hand, received probation for testifying at Carmody's trial and had his court costs waived.

"They needed to respect Chance Michael LeCroy," Danny LeCroy said of his son. "If we had to pay $700 to go down there and they were doing something, this wouldn't be an issue. But it became an issue

***

Greenholtz hopes his scheduling order can bridge the gap between family members and attorneys with competing interests in the justice system.

Any case may touch the docket 10 or 11 times a year, he said.

But each date involves several moving pieces: A clerk pulls the files, a courtroom officer transports the defendant from the jail, the prosecutor and defense attorney must be there at the same time to make announcements.

"Now it will happen two or three times," Greenholtz said. "And it will happen when there's something for the court to do. So we're reducing the costs, but also the impact to other people in the system whose interests haven't been given full account."

Prosecutors don't require victims or family members to return to Criminal Court unless it's a serious or high-profile case, Criminal Court Judge Don Poole said. "But (families) want to be there every time the case comes up, from arraignment to final disposition, and I understand that."

Poole said he is excited by Greenholtz's new idea and wants to see how it plays out. He said relies on a couple of trusted methods to alleviate the same concerns in his courtroom.

First, Poole asks during the morning roll call if any attorney asked a family member, victim or witness to be in court that day. He also sets a "disposition date" about four or five weeks into a case, which gives attorneys time to work out a dismissal, a plea agreement or a decision to go to trial. After or three of these dates, Poole makes it a goal to schedule a trial by six months into a case.

The third Criminal Court judge, Barry Steelman, said he studied other judges during his 11 years as an assistant district attorney in Hamilton County and developed the concept of "pretrial conferences."

About 30 to 60 days out from a trial, Steelman said he asks attorneys report to his courtroom and brief him on any outstanding issues. If they need help with anything, he can offer an order or issue a subpoena to keep the case on track.

"Judge Greenholtz's involvement is a beneficial thing because he's got a fresh set of eyes and I hope what he's planning on doing will be successful," Steelman said. "I think scheduling orders can be difficult to follow primarily because of the lack of resources available in the district attorney's office and the public defender's office."

Verna Wyatt, a co-founder of Tennessee Voices for Victims, said continuing to invest in victims is crucial since their rights can be lost in the shuffle of prosecutors and defense attorneys trying to mete out the right punishment for defendants.

"That's not a crime, giving a leg up to the victim, it's just sensible," Wyatt said. "We're the injured party here, yet we have to take off work, pay for parking. We come with all this anticipation and anxiety, and then it's delayed for another four months?

"That is the story of victims across the state."

Contact staff writer Zack Peterson at zpeterson@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow on Twitter @zackpeterson918.