There's no predicting what potential public health emergency looms on the horizon, whether it's a natural disaster, an emerging infectious disease or a bioterrorist threat.

This year, hurricanes and wildfires killed hundreds of people and dismantled health care infrastructure as they ravaged the United States. In 2016, still reeling from West Africa's Ebola outbreak, the world was struck by Zika virus when thousands of babies were born with serious, unexpected birth defects.

"Bottom line is, we need to pay attention to strengthening our public health preparedness efforts," said John Auerbach, president of Trust for America's Health, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that aims to elevate the nation's priorities in community health and disease prevention.

The group this week released a state-by-state report highlighting key indicators of health security and crisis preparation, such as funding, laboratory biosafety training and the ability for licensed nurses to provide care in other states.

Dr. Karen Remley, director of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said the report documents the nation's inconsistent, often reactive rather than proactive, approach to preparing for health emergencies, which relies heavily on federal emergency supplemental funding.

Score summary

9 out of 10: Massachusetts and Rhode Island8 out of 10: Delaware, North Carolina and Virginia7 out of 10: Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Minnesota, New York, Oregon and Washington6 out of 10: California, District of Columbia, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont and West Virginia5 out of 10: Georgia, Idaho, Maine, Mississippi, Montana and Tennessee4 out of 10: Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania3 out of 10: Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Texas, Wisconsin and Wyoming2 out of 10: Alaska

"After the sense of emergency dissipates, so does our attention to it," Remley said.

Trust for America's Health began conducting readiness reports in 2003, following the 9/11 and anthrax attacks. Auerbach said those were a "wakeup call" for the nation to rethink its response to disease outbreaks and disasters.

"We've seen dramatic changes in progress all across the country," he said. "But public health departments have often lacked the resources they needed to respond at times, facing declining funding at the federal, state and local levels, and there are certain areas of preparedness which have not been adequately addressed."

Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama were among 25 states that achieved five or less of the 10 key indicators, with Tennessee scoring five of 10.

Lacking in Tennessee were an accredited state public health department, a seasonal flu vaccination rate of at least half the population, 70 percent or more hospitals reporting meeting Antibiotic Stewardship Program core elements, membership in the U.S. Climate Alliance and a paid sick leave law.

Auerbach emphasized that the report isn't a comprehensive analysis, or a reflection of specific health program performance, but rather "snapshots" of a each state's preparation level and ability to address health emergencies based on the indicators, some of which are not within the control of the public health sector.

While the report pinpoints areas where the nation fails to fully support public health readiness, local health departments often shine despite policy and funding obstacles, and that was apparent during this year's hurricanes, Auerbach said.

"Some of the states lacking several of the measured indicators have nonetheless done a very good job of protecting the public," he said, adding that local health departments juggle a myriad of other, routine programs and also address ongoing crises like the opioid epidemic.

Emergency and public health officials in Hamilton County say that training and preparing for catastrophe is something they conduct regularly and take seriously.

Many different entities are poised to respond if an emergency strikes, said Tony Reavley, director of the Hamilton County Office of Emergency Management and Homeland Security, which coordinates widespread emergency efforts in the area. Reavley said his team performs drills constantly and uses large, planned events - like the Ironman competition and Riverbend - to practice.

"We are each responsible for a specific area, but when something really happens, we come together, and I think we work like a well-oiled machine," he said.

Sabrina Novak, emergency preparedness coordinator for the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department, is one of the many individuals who works with Reavley to develop community partnerships, train workers, recruit volunteers and write emergency protocols, such as the "point-of-dispensing plan" for rapidly distributing medicine or vaccines.

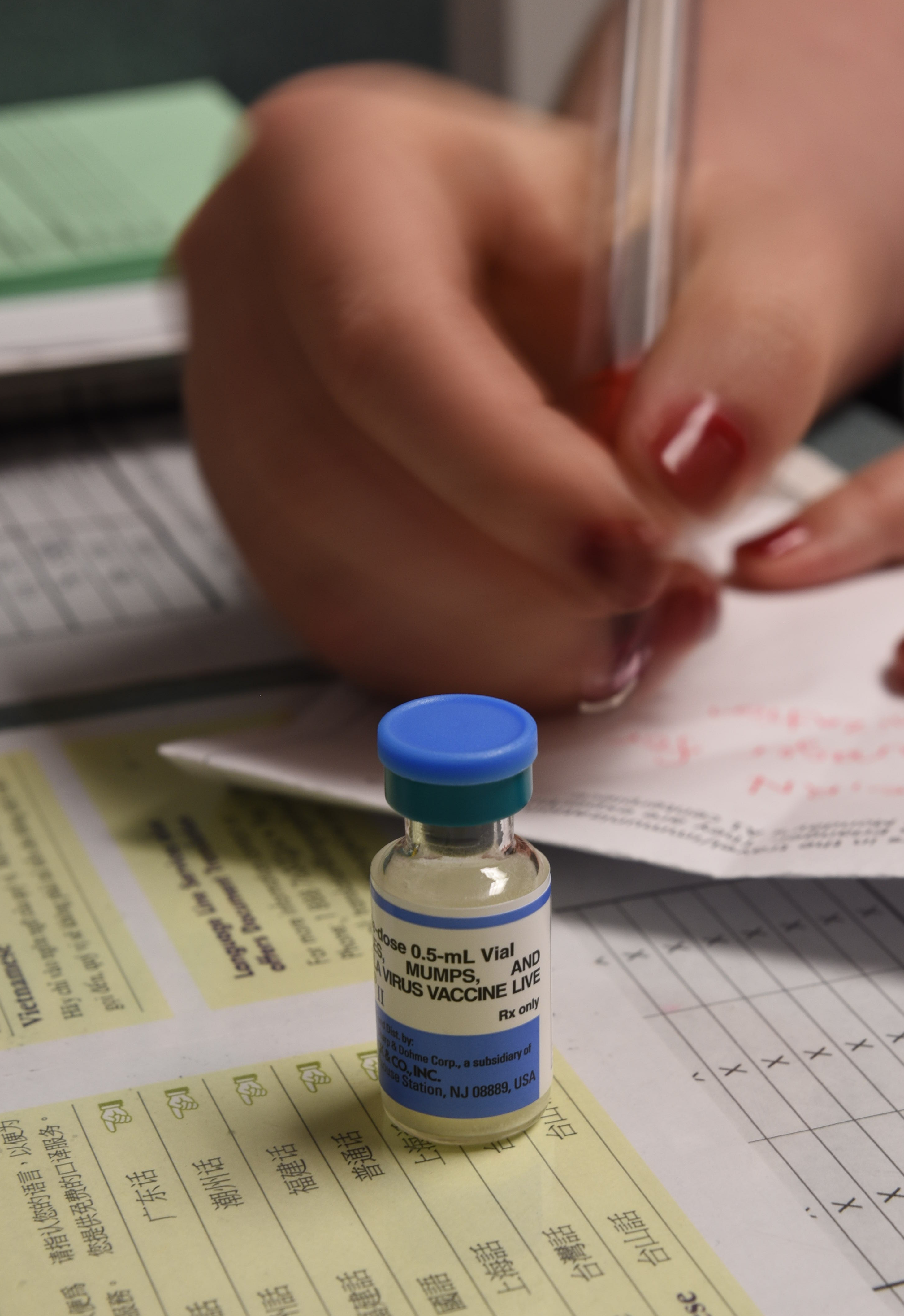

"There's planning processes in place to see how quickly you can get bottles in hand to 340,000 plus people - it could be utilized really for any type of communicable disease," she said.

Get prepared

Prepare your household for emergencies:Create and practice a household emergency planConsider pets and family members with special needsInclude meeting points, key contacts and individual assignmentsStock a disaster kit with important items, like cash, records and medicationsStay informed about current disaster informationDon’t rely on cell phones, which may not work during disasters

On Dec. 10, health department nurses Wendy Strange and Patti Holmes left St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where they gained first-hand experience aiding in disaster relief after Hurricane Maria.

"It was very eye-opening. What if we get total devastation here?" Strange said. "Just some of the things you don't think about, like providing food, special diets for diabetics, wound care – we got it all – so just thinking how you work through that."

For a month, they rotated between nearly 14-hour days caring for patients in a medical shelter and 10- to 11-hour days giving flu and tetanus shots outside in a tent, which served as a health department.

Ken Wilkerson, director of Hamilton County Emergency Medical Service, which oversees the ambulances and paramedics, said that emergency scenarios are both inevitable and evolving, so training, planning and coordination is a fluid process.

"The public needs to be prepared to do as much for themselves as is possible, but also to feel confident that there are plans and practices in place to address emergency issues," he said. "In today's world, we function daily with ever-changing threats."

Contact staff writer Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.