Questions about the potential impact of the new Republican tax bill are flying, but one of the biggest changes under the bill President Donald Trump signed Friday concerns health care, not taxes.

Starting in 2018, the legislation ends the Affordable Care Act requirement that everyone buy health insurance or pay a penalty - something U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., called "a particularly cruel tax to lower-income Tennesseans."

While unpopular, the individual mandate was originally written into the Affordable Care Act because - like all insurance - it needs healthy people enrolled to offset the cost of sick people. Experts believe that without this requirement, healthy people will drop their insurance, causing costs to rise and forcing more people out of the insurance pool.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates 13 million people will lose coverage by 2027, but also estimates a $338 billion benefit to the federal deficit because fewer people will be receiving Obamacare tax subsidies.

Republicans are celebrating the potential savings, which they need to pay for tax cuts expected to add $1.7 trillion to the deficit, according to the CBO. They say ending the mandate is a victory for those struggling to make ends meet, although many low-income individuals qualify either for an exemption or for subsidies that reduce insurance premiums.

"Most of the people who pay the individual mandate tax make less than $50,000 a year - so it's a good tax to repeal when you're writing a tax cut bill," Alexander said.

Scrapping the mandate worries others, though. Dr. James Powers, a professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, said he's "very concerned" about lost coverage.

"People who don't have health insurance don't get the care they need, they suffer worse outcomes, and when they do get medical care, if they do, they're sicker and it's more costly," he said, adding that providers also could face consequences.

"There's also a requirement, because you're a health care provider, to see uninsured people if they're sick - they come to the emergency room, and you can't turn them away," he said. "So there's a string of basically uncompensated care, a burden that particularly rural providers and hospitals will suffer."

Erlanger Health System already has seen its uncompensated care costs rise steadily over the last five years - from about $85 million in fiscal year 2013 to more than $110 million in fiscal year 2017.

Tennessee's rate of rural hospital closures is the highest in the nation, with eight closures since January 2010, and Georgia has lost six hospitals during that time. The hospitals not only provided care to rural residents, but drove local economies.

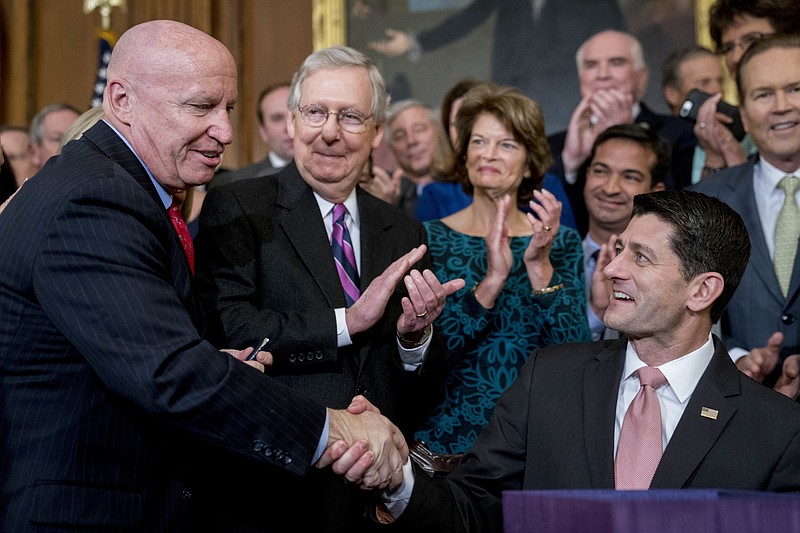

Others fear that adding to the deficit will lead to cuts in Medicare and Medicaid, programs long targeted by House Speaker Paul Ryan, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell recently refuted the possibility of cuts happening in 2018.

Powers said he is "afraid that if the cost of this budget deficit is spread out among many entitlement programs, Medicare is just one, that it's going to decrease access for patients and that providers will be less likely to see them because of reimbursement cuts."

Powers, whose patients are mostly older adults on fixed incomes, said cuts to these programs would be particularly detrimental to seniors.

"August in each year they're coming in saying, 'I've run out of medicines - I can't afford them anymore,' and their health suffers," he said. "Some might argue that we all have a responsibility to provide for our own health, and I agree with that, but I think that when you raise costs that it increases access barriers, and the more disadvantaged, sicker populations are going to suffer."

Contact staff writer Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.