Photo Gallery

Officials: Trump budget cuts threaten sewer, housing upgrades, aid to poor, homeless, elderly, public radio, TV

Local officials and nonprofit agency staffers are reacting with concern to President Donald Trump's proposed budget cutbacks, saying they may hurt efforts to improve dilapidated housing, upgrade sewer systems, help the homeless, and force local public radio and television stations to cut back on programming or even close their doors.

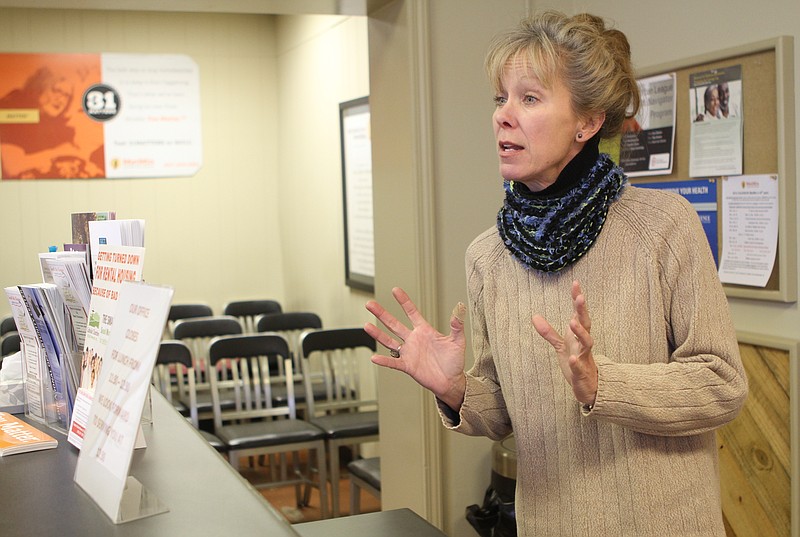

"I'm concerned about the blatant back-turning on the reality folks living in poverty experience every day," said Rebecca Whelchel, executive director of Metropolitan Ministries in Chattanooga, which focuses on preventing low-income families from slipping into homelessness.

It is unlikely Trump's budget will be adopted in its present form. Congress produces the budget and can choose to include or ignore a president's recommendations. Tennessee U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander made that point in a news release Thursday, saying "the president has suggested a budget, but, under the Constitution, Congress passes appropriations bills." Fellow U.S. Sen. Bob Corker, in his own release, emphasized the need to reform entitlement spending, such as for Medicare and Social Security, two agencies not cut by Trump's proposed budget.

But the Trump administration budget gives a more specific road map of the president's priorities than he had provided during the 2016 campaign.

Overall, the budget boosts spending for defense, homeland security (including building a border wall with Mexico), and aid to veterans. To avoid raising taxes to pay for those increases, it calls for steep cuts to Medicaid, as part of the health care reform legislation, and to most other federal agencies, including a 30 percent reduction in the budget for the Environmental Protection Agency, the elimination of Housing and Urban Development community development block grants, and getting rid of numerous federal agencies including the Appalachian Regional Commission and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which provides substantial funding to local PBS and NPR stations.

***

While the EPA is often criticized by business leaders for adopting regulations that drive up the cost of doing business, the agency also offers grants or loan guarantees to make it easier to comply with those regulations. For example, EPA low-interest loans help fund expensive renovations to the city's sewer system.

"There are four existing loans with multiple projects currently, and we are applying for another one now," said Justin Holland, Chattanooga's administrator of public works. "These are low-interest loans, less than 2 percent interest generally, where the EPA provides funding to the state [and] the state matches and manages the loans."

Pete Cooper, former head of the Community Foundation, noted that often the community block grants allow local governments to do things they need to do, but don't have the political support to justify raising taxes to do.

"There's not a lot of people marching in the street to get rid of homeless people," he said. But using block grants is "a way to address that issue, which has significantly improved in Chattanooga over the last several years, without forcing a local tax increase."

Each community sets its own goals for what to do with community block grant funds, with guidance from community meetings and a community advisory committee. In Chattanooga, for example, almost all of the funds are used to improve housing for low-income residents, according to Whelchel, a longtime member of the local advisory committee.

Some of the money has been used to repair dilapidated single-family housing, to allow it to continue to be used instead of being demolished, forcing the residents to find another place to live, Whelchel said.

"If you have a family or an individual living in a house or apartment that is substandard but paying $425 a month and they have an income of $733 a month for disability, that's a tight squeeze anyway," she said. "There is not another place to go to get $425 rent."

The city of Chattanooga has also used block grant funds to build sidewalks and for lead paint removal in low-income neighborhoods, said Donna Williams, the city's director of economic and community development.

"There's a great need out there," she said. "If we don't have [community development block grant] funds, some funds have to shift to the general fund budget or be eliminated entirely."

City Councilman Chris Anderson, who is on the board of the National League of Cities, spent Wednesday in Washington lobbying members of Congress against the block grant cuts. He said four members of the Tennessee congressional delegation agreed not to vote to cancel funding for the grants.

"While all of this may seem abstract to people in Washington, if we lose $2 million, real people lose their jobs and the city will likely have to stop providing certain services that so many of my neighbors depend on," Anderson said.

The Trump budget is unclear on one major local infrastructure project, funding to replace the lock on the Chickamauga Dam, a top priority for the TVA. Budget documents prepared for the Trump campaign last year identified the Chickamauga lock replacement as one of 100 infrastructure projects that could be funded as part of the president's proposed $1 trillion of spending for infrastructure.

But the preliminary budget released Thursday proposes to cut federal spending for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is paying for the $680 million replacement lock, by 16.3 percent from $6 billion to $5 billion in fiscal 2018.

***

Losing all of its federal funding would be devastating for local PBS station WTCI, said Paul Grove, president and CEO. "It is a door closer," he said.

WTCI, which covers 34 counties in Southeast Tennessee, Northwest Georgia and Northeast Alabama, has a budget of about $2.2 million annually, Grove said, of which about $700,000 comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which Trump's budget plan eliminates, and another $500,000 from the state of Tennessee. But the amount of money the state provides depends on how much federal funding is available, so a cut in Corporation for Public Broadcasting monies would lower the state funding as well, Grove said. The remaining 50 percent of WTCI's budget comes from viewer donations.

Besides paying salaries for a staff of 20 people and covering the cost of utilities, the funds also pay for PBS programming such as "Sesame Street" and "Downton Abbey," and for producing local programming.

Grove said he is hopeful local support for the station will convince lawmakers to vote against cutting its federal funding. He noted that public broadcasting generally gets broad support from the public as a good use of tax money, citing a Roper study saying "PBS is the most trusted American institution for the 14th straight year, and taxpayers believe we're the second best use of their dollars, second only to military defense."

Elsewhere locally, WNGH, the public radio station that reaches Calhoun, Chatsworth, Dalton, Ellijay and Tunnel Hill, could face challenges under the proposed federal budget.

The station is part of the Georgia Public Broadcasting network, which received a federal grant of about $3.4 million last year. That covers most of the $4.5 million in dues the network owes PBS and NPR. The rest of the money comes from private donors.

GPB is the third-largest public broadcasting network in the country, Vice President of External Affairs Bert Wesley Huffman said. With Trump's budget cutting federal grants for public broadcasting, the network may be able to function on the strength of private money, at least at first.

But smaller stations in other parts of the country would fold without the federal funding. They use the money to pay their dues to PBS and NPR. And if PBS and NPR aren't getting money from the smaller stations, they may have to charge more money to bigger networks. This, in turn, would force GPB to get more money from wealthy donors.

"Could we survive?" Huffman said. "Yes. Maybe."

Another agency on the chopping block, the Appalachian Regional Commission, provides several million dollars in grants annually to states in the 13-state Appalachia region, including 34 counties in Tennessee in 2016. Money went for projects such as improvements to a boat facility in Rhea County ($500,000), to the health department in Bledsoe County to improve access to health care ($500,000), and for improvements to an industrial park in Dunlap ($200,000).

In North Georgia, local governments would likely need to find new funding sources for some projects, potentially from local taxes or state grants. Since 2010, the block grant program has given $4.1 million to Catoosa County, Gordon County, Whitfield County, Calhoun, Chickamauga, Fort Oglethorpe and Summerville.

The money has gone toward expanding sewer systems, renovating a senior living center in Walker County, and expanding the Georgia Chamber's Resource Center, a nonprofit organization in Calhoun that helps people with disabilities.

MaryBrown Sandys, director of marketing and communications at the Georgia Department of Community Affairs, said it's too early to speculate on how Trump's budget would impact those projects in the future.

Staff writer Tyler Jett contributed to this story.

Contact staff writer Steve Johnson at 423-757-6673, sjohnson@timesfreepress.com, on Twitter @stevejohnsonTFP, and on Facebook, www.facebook.com/noogahealth.