Melissa Beavers was desperate 11 years ago.

The police had found methamphetamine on her, and the state took away her three children. She was broke. And to get her kids back, Georgia's Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) demanded she complete a list of objectives within 18 months.

Among her orders? Attend counseling for post-traumatic stress disorder, the lingering effects of sexual abuse. Counseling seemed like a luxury for rich people, but her DFCS case worker referred her to a man who let clients pay whatever they felt comfortable. That's how she met Daniel Staats.

Almost immediately, Beavers felt uncomfortable. At the time, she said, Staats was practicing out of a house in Chatsworth, Ga. The house was a mess, and they met in a room in the back - a converted bedroom, she figured.

Beavers said Staats quickly launched into the whole matter of sexual abuse. She said he pressed her for details. What exactly happened to you? How, precisely, did you feel as it was happening? He didn't ask about the emotions she felt as a result. He didn't seem to want to connect any dots between the abuse and her current behavior.

Staats’ response

Asked about the women’s allegations in the story, Daniel Staats told the Times Free Press in an email, “If you take conversations out of context, they can sound bad. … Problem with helping people with their issues is confidentiality. They can say whatever, take stuff out of context, and say half-truths; but the only way to defend the truth would be to break confidentiality.”In cases of sexual abuse, he said a counselor has to ask the client what happened to “help them overcome it.”

"It just seemed like somebody interested in the details of your trauma," Beavers recalled to the Times Free Press in an interview last week.

Worried about DFCS' demands, Beavers returned to Staats for a second visit. The second visit wasn't any better.

She said he insisted on hugging her. She said she resisted, told him she didn't feel comfortable. She said he tried again, saying something along the lines of, "It's OK. I'm a counselor."

Beavers left. She wondered if she would see her children again.

"You start questioning yourself," she said. "You're like, 'Was I just stupid? Was I just overreacting?' Because he really didn't do anything - but he kind of did. He made you so uncomfortable. If we feel uncomfortable, nine times out of 10, there's a reason."

After those 2007 sessions with Staats, Beavers told another counselor what happened. She received help elsewhere, got her children back and graduated with a degree in social work. She is working on her master's degree and helping with a local mobile crisis response team, trying to help people who call for help.

But over a decade, she occasionally thought about Staats. She never reported his behavior. Frankly, she didn't know who you go to for something like that.

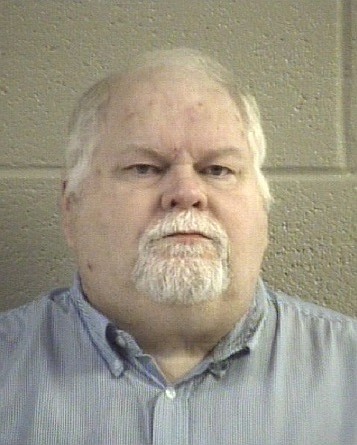

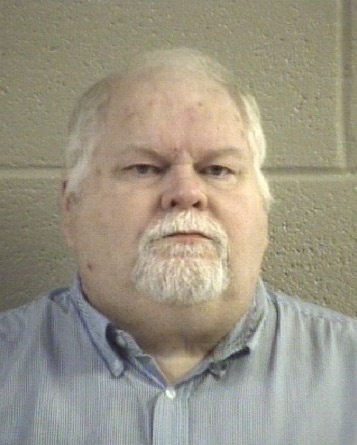

Last month, though, she saw news reports of Staats' arrest. According to a Dalton police news release, the counselor sat down next to a client during a visit in July, asked her inappropriate questions, fondled her breast and exposed his genitals before the woman performed oral sex on him. The police have charged him with sexual assault by a psychotherapist; a counselor is not allowed to have a sexual relationship with a client.

The case has led to a wave of allegations against Staats, who operated a nonprofit organization called Helping the Hurting. Dalton Police Department spokesman Bruce Frazier said about 10 women have come forward since the initial media reports on the case three weeks ago. Their reports have not led to more charges. But Frazier said the women have stories claiming Staats acted unethically toward them.

"The investigation is very much still ongoing," Frazier said.

Including Beavers, the Times Free Press interviewed three women who said Staats acted inappropriately toward them during visits to his office. They, too, described incidents that weren't crimes. But all three felt hung out to dry, as if a state agency could have prevented the harassment.

There are a couple of problems here, as they see it.

First, Staats is not licensed with the Georgia Composite Board of Professional Counselors, Social Workers and Marriage and Family Therapists. Like many states, Georgia allows you to practice counseling without a license if your work is rooted in biblical doctrine. As a result, Staats did not need to receive continuing training on ethical practices. He also was not subject to discipline by the board if a woman claimed he harassed her. A spokeswoman for the Georgia Secretary of State's Office said the agency cannot release complaints on any counselors, so it's hard to know whether anyone tried to alert the board.

Second, women often went to Staats as punishment for run-ins with the law. While Beavers visited him to satisfy her DFCS case plan, Racheal Peters, a spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Community Supervision (DCS), estimates 10 probationers were actively seeing Staats when the agency pulled them out last fall, having learned the counselor was under criminal investigation.

Said Beavers: "If you don't go back to [Staats], it's not like, 'You don't get your therapy.' If you don't go to him, you're going to jail. If you don't go to him, you're not going to get your kids back. This isn't these agencies telling him that, per se, that you have to go to him. But when they hear 'Free services' to complete a case plan, to complete probation, to complete parole, they're going to accept those free services and deal with whatever comes with it."

One woman told the Times Free Press she accompanied her boyfriend to Staats' office in September or October because he was on probation. She requested anonymity, her boyfriend not wanting to be outed for a criminal history.

When she arrived, she said Staats asked her boyfriend if she could sit in with them. Her boyfriend didn't mind. But during the meeting, she said, Staats made her uncomfortable.

He started asking her boyfriend what he liked to do for fun. Then he turned to the woman, who was pregnant. She recalls Staats saying that he knew what she liked to do.

"He was saying how Hispanics like having sexual intercourse; how they have a lot of kids," she told the Times Free Press. " I felt really disrespected. I don't know; I just felt weird."

She said her boyfriend initially chose Staats because a DCS officer gave him a list of acceptable counselors, along with a price for each person. Staats was the cheapest, she said.

According to a Dalton police report, another woman said she went to Staats after seeing his services were the cheapest on some sort of list. The report does not explicitly say that the woman was on probation, but it does say she was "ordered by the court to be evaluated by a counselor for her case."

Peters, the Department of Community Supervision spokeswoman, said the agency does not provide any such list to probationers. She does not know why two women in the Whitfield County area would independently describe a list. She said DCS is not responsible for the counselors that probationers see. Officers may tell you what counseling services are available, but they don't endorse any of them. When it comes to counselors, Peters compared the role of DCS to that of Google.

She said a state board is supposed to make sure counselors are acting appropriately. But Staats was not subject to the board, given that he didn't have a license. Asked why DCS doesn't just introduce probationers to licensed counselors, Peters said an action like that would infringe on a probationer's right to choose a provider.

"It's not a referral," she said, of a DCS officer's role in finding a counselor. "I think that's pretty clear. Even if it was a referral, it's a stretch to suggest that DCS should be regulating private providers who have a regulatory agency within the state. There's a separation there that has to be maintained. Other areas of the government are responsible for holding professional counselors accountable. And it's not DCS' place to interfere with that."

Division of Family and Children Services spokesman Walter Jones, meanwhile, said his agency's policies should keep them from associating with someone like Staats. Asked about Beavers' case, Jones said he could not comment on a case worker's actions 11 years ago. But since 2013, he said, the agency has maintained a policy of contracting with counselors - but only if they pass a criminal background check and are licensed with the state.

Peters said DCS officers would keep probationers away from unlicensed counselors if a judge specifically wrote that in a court order. But Conasauga Judicial Circuit Chief Judge William Boyett said that's not a fair approach.

In his Whitfield and Murray county courtrooms, he said, he relies on the advice of DCS officers to decide what counselor a defendant should see. He expects them to know about the counselors or their centers.

"We do order people to have mental health counseling," Boyett said. "But it's supervised and approved by probation."

There is another question: Should Christian counselors be allowed to operate without a license?

Dr. Robert Shaw, director of credentialing at the American Association of Christian Counselors, said most states have a carve-out provision, allowing members of the church to provide counseling without a state license. The exception exists because many pastors view counseling as a key element of their ministry. Generally, Shaw said, lawmakers have argued the state should not interfere with a pastor's work.

But some states create limits on Christian counseling. Some ask you to be tied to a church, as opposed to running a standalone business, Shaw said. That is not the case in Georgia. Since 1984, the state has allowed Christian counselors to run private businesses or nonprofit agencies without licenses.

Jon Harris, a licensed professional counselor and the director of the Christian-based Summit Counseling Center in Chattanooga, said the law in Tennessee is similar. He said a case like Staats' should not change the law. Loopholes will always exist, he argued. For example, if you needed a license to be a counselor, someone might instead open up a business as a "life coach" and attract the same clients.

Mark Carpenter, another Christian counselor in Chattanooga, said forcing Christian counselors to be tied to a church would not work. A counselor could then claim his operation is a church, creating a different wave of uncertainty.

"That is the danger within the whole industry," Harris said. "Not only with the church and Christian counseling, but across the board: with all of mental health and behavioral health."

One woman who talked to the Times Free Press said no agency pushed her toward Staats. Twenty years old at the time, she and her husband wanted marriage counseling. She saw that Staats charged only $20 a session. At first, he seemed like a good counselor asking good questions.

She and her husband eventually separated in 2012, but she visited Staats again. This time, she said, he spent much of the session telling her she was beautiful, that no man should reject her, that she should feel welcome to send pictures to him. She said he also insisted on hugging her. She stopped going to him then, though she said he continued hitting on her in Facebook messages.

Still, she didn't try to alert anybody.

"I thought it was inappropriate and made me uncomfortable," she said. "I didn't think anything had been done that I could report."

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at 423-757-6476 or tjett@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @LetsJett.