American colleges sorting through a record number of applications from China are increasingly turning to video interviewing services to assess students' language skills, get a feel for their personality - and weed out fraudsters.

The recorded interviews, recommended by dozens of schools, have emerged as a way to address cheating concerns highlighted by a breach that forced a cancellation last weekend of SAT exams in China.

"If you believe in all the fraudulent claims, and there certainly has been some documentation out there, then the one true equalizer is getting an unscripted interview with a limited English speaker," said Kregg Strehorn, an assistant provost at the University of Massachusetts. "That will put anyone's mind to rest."

Admissions officers are wary of fraud in applications from all countries, including the U.S., but attention has focused on China with the huge rise in applications from the country's middle class. More than 300,000 people from China studied in the U.S. last year, up from roughly 60,000 only a decade ago.

College officials and industry consultants describe a range of issues including plagiarism, purchased transcripts and surrogate test-takers. Evidence is largely anecdotal and the topic can be a delicate one for colleges, which receive a boost by enrolling international students who often pay full tuition.

"It's the kryptonite of international education," said Daniel Ghur, who has studied fraud as the director of the Illuminate Consulting Group in California.

One service provider, InitialView, was launched in Beijing in 2009 by an American couple. While many colleges have interviewed students themselves on the Internet, the company offers verification of student identities. InitialView conducts interviews in 14 cities across China and has begun operating in other countries. The company charges a one-time fee of $220 and will send a recording of the interview to as many schools as the student wants.

"The schools that use us, they just want to have integrity in their process," company founder Terry Crawford said.

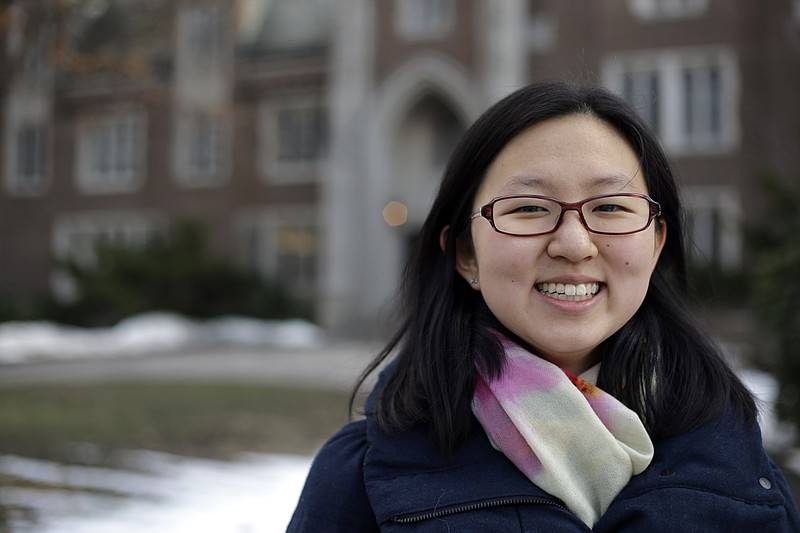

A Wellesley College student, Linda Liu, said she sat for an InitialView interview at the urging of a counseling agency that helped her with college applications. Liu, 18, said the service has grown in popularity among students at her Beijing high school and she saw it as an opportunity to tell American schools more about herself.

"It's a way to show yourself, showing actually who you are, in a very direct way instead of just showing it in on paper or in essays," she said.

For colleges, the interviews offer a baseline for assessing students from a different system for secondary education. Even as American admissions officers have visited China to recruit students and better understand local institutions they say it remains difficult to know how to weigh the significance and validity of varied transcripts and recommendations.

"It's one of those 'the more you know, the less you understand' situations," said Rick Clark, admissions director at Georgia Tech. "You cannot apply an American filter."

Georgia Tech, which now reviews interviews from non-native English speakers in any country, started with applications from China several years ago to find students who would adapt well to campus life after some professors noted a lack of classroom interaction by Chinese students, Clark said. In practice, he said, the interviews on occasion have helped to flag potential fraud in cases where statements in an interview blatantly contradict material in a student's application file.

Scrutiny of Chinese application materials was expected to increase after the College Board, the New York-based nonprofit organization that oversees SAT registrations, canceled the exams at 45 testing centers in China and Macau last weekend over concerns that some students might have accessed copies of the exam in advance. The company wouldn't say how many students might have seen the tests, or how they did so.

Admissions officers say suspected fraud has turned up in applications from many countries. One challenge in vetting applications from China, they say, is separating out the work of the many third-party agents and consultants who promise to help students win admission to American universities.

At the University of Oregon, which recommends the interview services, admissions director Jim Rawlins said he worries more about Chinese students becoming victims themselves than about them committing fraud. When discrepancies are found in Chinese applications he said the university often suspects consultants or agents who submit fake documents, possibly without students' knowledge.

"Every now and then a student gets turned down and, when told why, is very surprised to hear what was done on their behalf," he said.