WASHINGTON (AP) - Last-ditch court appeals could block the executions of two Arkansas inmates who are scheduled to be put to death Monday after spending more than two decades behind bars. What's left to appeal after so many years? A look at some issues that can stop a lethal injection at the last minute.

___

Q: WHAT'S THE SITUATION IN ARKANSAS?

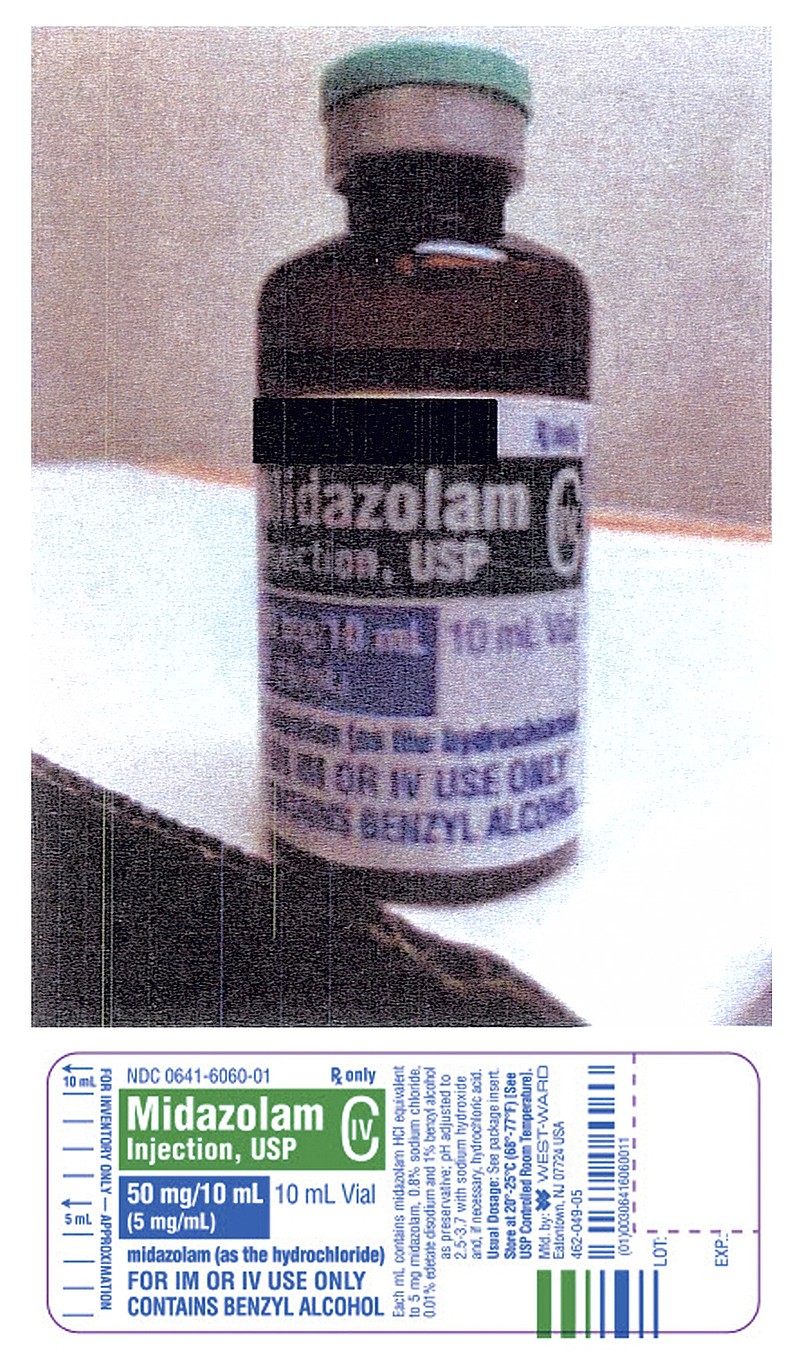

A: Arkansas sought this month to carry out the nation's most ambitious execution schedule since the death penalty was restored in 1976. Authorities initially planned to put eight men to death before April 30, when the state's supply of midazolam expires. That's the drug used to render inmates unconscious before they receive other injections to stop their hearts and lungs.

So far, only one person has been executed. Courts have blocked four lethal injections, including at least one that was called off only hours before the inmate was to enter the death chamber.

___

Q: WHAT ARE THE LATEST APPEALS?

A: Lawyers for the men who are scheduled to die Monday have filed legal challenges based on the inmates' health, saying their poor physical condition could interfere with the lethal injection and subject them to extraordinary pain. Marcel Williams is obese and diabetic. Jack Jones has diabetes, high blood pressure and has had a leg amputated in prison. A federal judge on Friday rejected those claims, but attorneys for the men have appealed to higher courts.

___

Q: WHY DO SUCH DELAYS TAKE PLACE?

A: Inmates can spend decades appealing their convictions and death sentences in state and federal courts. The average time between sentencing and execution for prisoners executed in 2013 topped 15 years, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics.

By the time an execution takes place or is stopped, four or more different courts are supposed to have examined the entire case, including the trial record, outstanding legal issues, assertions of innocence and claims of constitutional violations or newly discovered evidence. But it's common for inmates to plead with varying success that key elements have never been examined by a court. New issues also arise late in the process, including questions about the effect of execution drugs.

___

Q: WHAT'S THE PROCESS?

A: The Supreme Court has the final say on almost every execution, but the justices reject all but a few emergency appeals by inmates.

The justices and their clerks know well in advance when executions are scheduled and where. A court official informally known as the death clerk keeps everyone up to date and communicates often with lawyers for inmates and the states as the date of execution nears.

As lawyers for condemned inmates press the case for delay in state and lower federal courts, the Supreme Court receives information about developments and, eventually, copies of those decisions.

Most often those lawyers press their arguments at the highest court in the country in a final attempt to save their clients' lives. Less often, it's the state that seeks permission to proceed after a lower court has blocked an execution. That's what happened Monday in Arkansas.

___

Q: WHAT HAPPENS AT THE HIGH COURT?

A: When those appeals reach the Supreme Court, they go first to the justice who oversees the state in which the execution is scheduled. But death penalty appeals almost always are referred to the entire court.

The justices typically do not meet in person to discuss these cases, but confer by phone, and sometimes through their law clerks, according to the court's guide to emergency applications.

It takes five justices, a majority of the court, to issue a stay or lift one that has been imposed in another court. The overwhelming majority of last-minute appeals are denied, often without comment.

Occasionally, one or more justices will dissent from the decision to let the execution take place. Even more rarely, a justice will explain why.