Meteors and other space rocks streak through the skies every night, and four camera stations spread over the tri-state area keep watchful vigil, recording important data for researchers.

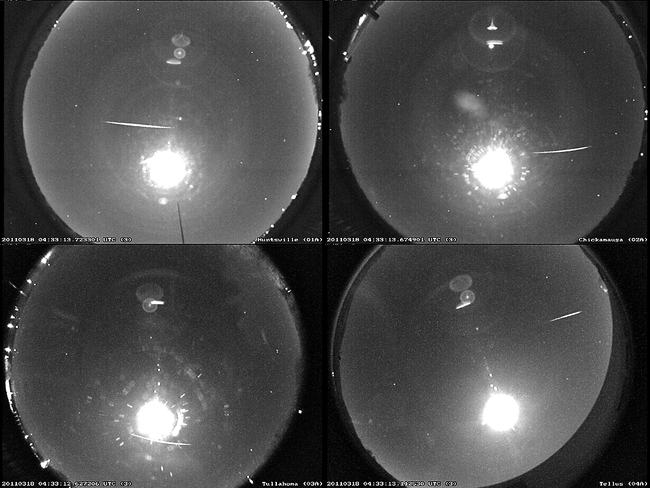

NASA operates the All-Sky Fireball Network with the four cameras, two of which are within 30 minutes of Chattanooga, to collect data about how much, how often and how quickly space rocks fly toward Earth.

Unmanned cameras have been placed at the Walker County Schools space observatory in Chickamauga, Ga., as well as at the Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville, Ga.

NASA also operates a camera in Huntsville, Ala., at the Marshall Space Flight Center as well as in Tullahoma, Tenn. And in the coming year, the space agency hopes to expand the skywatching effort.

"When you start out building a camera network, you want your first few stations close by so you can work out the bugs and resolve issues," said William Cooke, head of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office, based at the Marshall center. "We now have enough experience and confidence to expand to locales far from Huntsville."

The cameras operate remotely through the Internet, and the camera and computer cost roughly $1,000. Cooke sits down at his desk every morning and browses a handful of videos and images of meteors captured the evening before.

Every day, 100 tons of meteoroids - fragments of dust and gravel and sometimes even big rocks - enter Earth's atmosphere, NASA says. The vast majority are too small to pose a threat, turning into dust or shrinking to a nonthreatening size as the atmosphere slows them to a safe speed, research shows.

But with more than one camera angle, NASA scientists can tell how fast and at what trajectory meteors are traveling.

"All of this is valuable, as it helps validate and improve our models of the meteoroid environment near Earth, which are used in designing spacecraft," Cooke said. "It also helps to check our meteor-shower forecast models, which are used in spacecraft operations."

It also makes for cool Internet browsing for people who look to the sky, see a meteor and get curious. Computer software calculates all the spotted meteors' orbits and allows Cooke to share a wealth of information.

"If someone calls me and asks 'What was that?' I'll be able to tell them," he said. "We'll have a record of every big meteoroid that enters the atmosphere. ... Nothing will burn up in those skies without me knowing about it."

NASA plans to expand its network of cameras in clusters of five, so locally there's room for one more camera, Cooke said.

"I plan on putting one more camera in this area and am eyeing sites somewhere along the Tennessee and North Carolina border," Cooke said. "After that, I plan on placing another group of five cameras somewhere along the Atlantic seaboard and another group of five somewhere in the Ohio and Kentucky region."

Anyone interested in pitching a site should contact NASA online, but there are guidelines. The cameras work best in areas with a clear horizon free of trees, Cooke said. There can't be much bright light, and there must be a speedy Internet connection available.

Meteor hunters can use the NASA data to track where a space rock might have landed and go search for it.

"Most meteorites fall in the ocean, lakes, forests, farmers' fields or the Antarctic," said Rhiannon Blaauw, who assists Cooke. "And the majority of those meteorites will never be found. But our system will help us track down more of them."

Contact staff writer Adam Crisp at acrisp@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6323. Follow him online at www.facebook.com/crisp reporter and www.twitter.com/adam_crisp.