The number of extremely poor neighborhoods in Chattanooga and the region -- those with poverty rates above 40 percent -- more than doubled from 2000 to 2009, a new report shows.

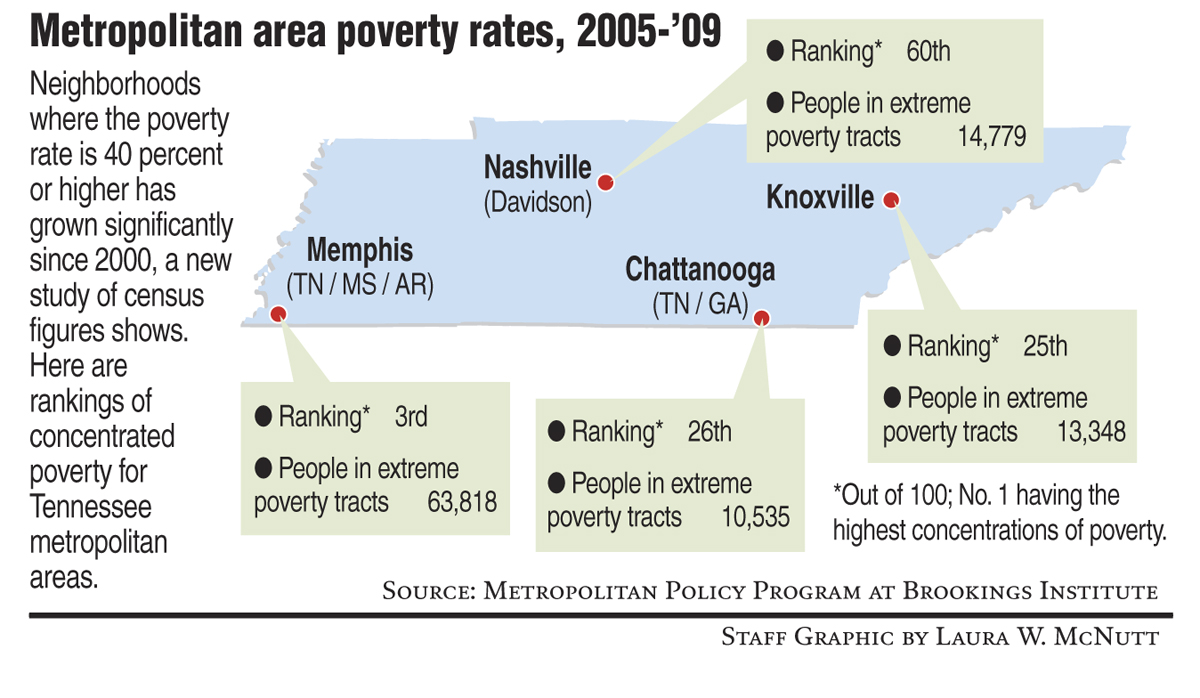

The number of people living in the poorest census tracts in the Chattanooga region grew by more than 4,200, to 10,535, in the period, according to "The Re-Emergence of Concentrated Poverty," from the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program.

The Washington, D.C.-based Brookings Institute is a liberal-leaning nonprofit that researches social issues.

"We lost ground against concentrated poverty in the 2000s," Elizabeth Kneebone, a senior research associate at Brookings and lead author of the report, said in a news release. "More people are living in areas that are extremely poor, and concentrated poverty now affects a greater swath of communities than in the past."

In the release, Kneebone noted that the federal poverty level in 2010 was $22,314 annually for a family of four.

In Chattanooga, some of those newly poor people show up at the Chattanooga Community Kitchen on 11th Street.

"Within the last two years we have seen increases in the number of intact families and the first-time homeless," said Jens Christensen, assistant director of the community kitchen. "These are the people who have no idea of how to navigate the services system, people that kind of defy the stereotype of homelessness."

The Brookings report, based on U.S. census figures, states that at least 2.2 million more Americans now live in high-poverty neighborhoods than did in 2000.

In Chattanooga's metropolitan statistical area -- Hamilton, Marion and Sequatchie counties in Tennessee and Catoosa, Dade and Walker counties in Georgia -- the number of high-poverty census tracts rose from four to nine. Several neighborhoods, most inside Chattanooga's city limits, saw poverty concentrations grow by 10 percent or more.

All of Dade County and large swaths of Walker, Marion and Sequatchie saw poverty rates rise, and the overall share of the poor population in high-poverty census tracts rose to 14.9 percent in the metro area and 32.2 percent in Chattanooga.

Jobless and homeless

John is one of those newly poor people. In his 50s, with wire-rimmed glasses and a fringe of neatly clipped gray hair around a bald pate, he wears a rust-colored corduroy shirt with a silver Cross pen in the breast pocket as he sits for an interview at the Community Kitchen.

John doesn't want his last name used. He's ashamed to be jobless and homeless. He had a successful career in sales and marketing, but his job went, his savings ran out and he had nowhere to turn.

When he describes signing a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development form certifying that he's living at a rescue mission, John buries his face in his hands for a moment.

"It's the hardest thing I ever had to do in my life," he said, voice thick with tears. "It's very difficult to admit to yourself what you have to write on that form. At no time in my life did I ever believe I would be in this situation."

John said he's been looking for work, but there are fewer jobs than there used to be. Most job ads are on the Internet and applications are answered by email.

"It's kind of hard to sell yourself when they're not actually talking to you," he said.

No surprise

The new numbers from the Brookings Institute don't surprise Rick Mathis, interim CEO/director of research and analysis at the Ochs Center for Metropolitan Studies in Chattanooga.

An Ochs study last year found a 6 percent decrease in employment in the Chattanooga metro statistical area between 2001 and 2009, Mathis said in an email. He said most people who live in pockets of extreme poverty don't have access to jobs close by or to transportation to job sites such as Volkswagen and Amazon.

"Addressing the extreme poverty in these neighborhoods requires additional planning to improve transportation and to create jobs in areas accessible to these neighborhoods," he said.

And because people with college degrees are more likely to have stable jobs, Mathis said the region should focus on increasing college graduation rates and attracting college graduates to the region.

He said the Ochs Center's 2012 report will have more information on economic and demographic changes, including 2012 census data.

A lesson?

The poverty numbers also didn't surprise a group of Occupy Chattanooga members standing on a street corner outside City Hall, sheltered from drumming rain under a blue tarp.

Daniel Cowgill, 21, a college student, said he's studied business management and trained as a chef but can't get work.

"I can't get a job because I don't have an address. I don't have an address because I can't get a job. There's a problem with that," Cowgill said.

Standing nearby, Joy Day, 54, has a master's degree and had a corporate job until she was laid off in June. She compares the Occupy movement with the progressive forces that took on the 19th-century robber barons, leading to legislation protecting workers and benefiting the whole country, she said.

"We learned that lesson. Now we're having to relearn it," Day said. "I'm not surprised to see that poverty is creeping out of traditional confines to the middle class. Now maybe we can get something done."