Karen Doche knows what she's up against.

People with bachelor's degrees are out there looking for jobs, people with master's and doctorates, too. Vice presidents who used to wear dry-cleaned suits are looking for jobs. There are men, maybe bigger or quicker or younger than her.

Still, she puts in the applications, works to find the work, and tells herself it isn't her fault she's one of millions still unemployed in this country because factories folded or shareholders pressed to shed costs even if that meant shedding people.

Two years ago Doche was laid off from the textile mill where she had worked for 23 years. Hundreds of others got pink slips over the next few months, too. A few of them have found work recently, and she holds on to this news.

Holds on as tight as she can, when the phone doesn't ring, when people give her strange looks at the bank where she cashes her $230-per-week unemployment check.

"You just keep going," said Doche, who lives in Red Bank. "You can't give up."

Work is a funny thing. People hate it: the hours, the bosses, the commutes. They can't wait to get away from the office or off the factory line for a long Labor Day weekend on the beach or slurping watermelon by the pool.

But people love to work, too. What they do becomes who they are; you can see it by the way they introduce themselves. It's a reason to wake up, a place to go. And they need to keep working, to pay credit cards and power bills and buy groceries.

These mixed emotions are painfully clear to the unemployed. They don't get as much enjoyment from a holiday. They wish they had a job to escape from.

Without the security, confidence crumbles, said Ruby Porter, a teacher at Re:Start, an adult training center in Chattanooga. Re:Start has worked to help more than 50 dislocated workers over the last few years, including Doche, get their GEDs and qualify to compete for new jobs.

Every one of them had been a solid worker, she said. They had decent-paying jobs for 10 or 20 or 30 years.

And then the work was gone.

"It's devastating when you have a job and all the sudden you don't," Porter said.

Doche, now 48, dropped out of high school as a freshman. She got married, had a baby, and by 22 was working at R.L. Stowe, a family-owned textile company that spun and dyed cotton and cotton-blend yarns at four plants in Tennessee and North Carolina.

When business was good a decade ago, she worked six days a week, mandatory overtime. She eventually became a section leader and earned $10.42 an hour overseeing work on the spinning frames.

Shuttered textile manufacturers speckled the South as businesses relocated for cheaper labor overseas, but R.L. Stowe was one of the few that stayed open. Then at Christmas in 2008, workers were told to take a week off. Then three weeks off.

And on Jan. 30, 2009, Doche was told the company was going out of business because of a recession-driven nose-dive in sales. The owners would liquidate what was left and sell off parts to anyone who would take them, officials said.

She, along with 350 others in the Chattanooga area, would need to sign up for government assistance and think about her next steps.

Doche had spent years memorizing the ins and outs of spinning machines in a mill operation and practiced the same motions thousands of times, day after day. Now the world was cracked open. She could do anything with her life, except what she knew best.

In the newspaper, the few job ads all looked the same: GED required, high school diploma required. So she made her mind up to start from the beginning. Go back to what she should have learned freshman year and move forward.

"You have to get it to get a job," she said. "This would be the only opportunity to get it."

In Chattanooga, 23,190 people officially are counted as unemployed, many competing with the other jobless across the state and the thousands of unemployed from neighboring states.

The last count of the long-term unemployed like Doche - those without work for a year or more - now comes to 4.5 million nationally.

And women are finding it harder to reclaim employment even though men lost twice as many jobs when the economy locked up starting in late 2007. Men gained 768,000 jobs nationally from 2009 to 2011, while women lost 218,000 jobs in the same period, a recent Pew Research Center study shows.

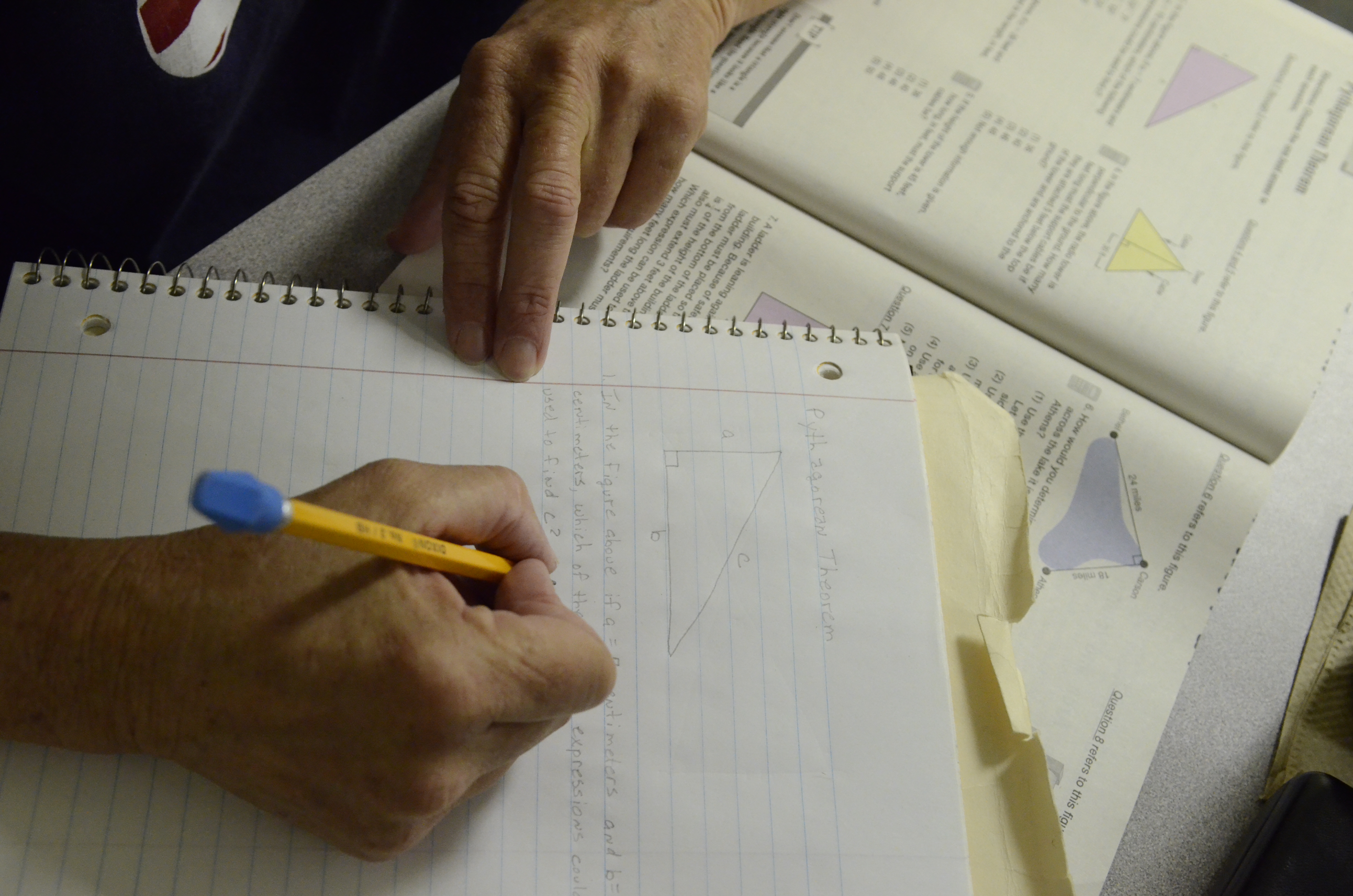

A month ago, Doche put in an application at a nursing home and a sign company, but she hasn't heard anything. Several days a week she goes to Re:Start to study for the GED test that she can't take until January.

She has taken it three times this year, and has to wait for the retake. The math keeps stumping her. She lacks just 10 points to pass.

"It's like your hands are tied," she said. "I ask myself, 'Why couldn't I have passed the test and moved on?'"

Doche used to collect Harley-Davidson memorabilia. She even bought a rare orange Harley once with money she saved while working for R.L. Stowe.

She remembers picking up her checks every Thursday, and that feeling of control.

That was her money. The money she earned.

When she went to the grocery store, she bought what she wanted and didn't have to pick generic brands or count apples.

"You do without a lot," she said, thinking about her life without a job.

Her unemployment checks will run out in a few weeks, but she feels change coming. Her boyfriend, with whom she has lived for several years, finally got a job last month.

"I talk to the man upstairs quite a bit," she said.

When her chance comes again, she'll be relieved. But, even with a new job, things won't feel the same.

"I like to work," she said. "But it's hard knowing I have to take whatever I can get."