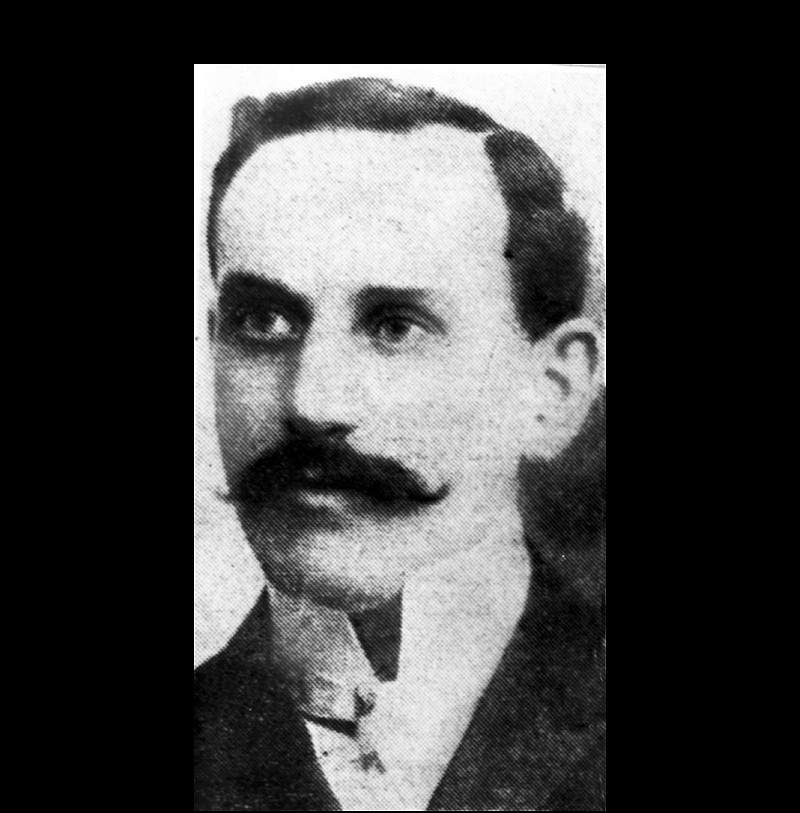

Most Chattanoogans are familiar with the story of Adolph Ochs, the young publisher of The Chattanooga Times who went on to establish a publishing dynasty at The New York Times. However, few know about the role another Ochs family member played in Chattanooga's development.

Shortly after acquiring the local Times, Adolph was joined by his parents and siblings. The entire family soon adopted Adolph's enthusiasm for his new home and committed themselves to its growth and progress. Chief among them was Adolph's younger brother, George.

George Washington Ochs, born in 1861 in Cincinnati, spent his early years in the shadow of the Civil War. The conflict created deep divisions in the Ochs household. Ochs' father, Julius, served in the Union Army. His mother, Bertha, was an outspoken Southern sympathizer who was once caught trying to smuggle medicine across the Ohio River in George's baby carriage. George's childhood, like Adolph's, was one of penury and hardship. Unlike his older brother, however, George was too young to work to help support the family. As a result, George acquired one thing that his renowned older brother would never have -- a formal education.

After graduating from the University of Tennessee in 1879, George arrived in Chattanooga to work for his brother's fledgling enterprise. The younger Ochs became a familiar sight on Chattanooga's muddy streets and soon earned a reputation as a fair-minded reporter. Others, however, were less pleased with his coverage. On one occasion, George was compelled in self-defense to shoot a man who attacked him over his writing.

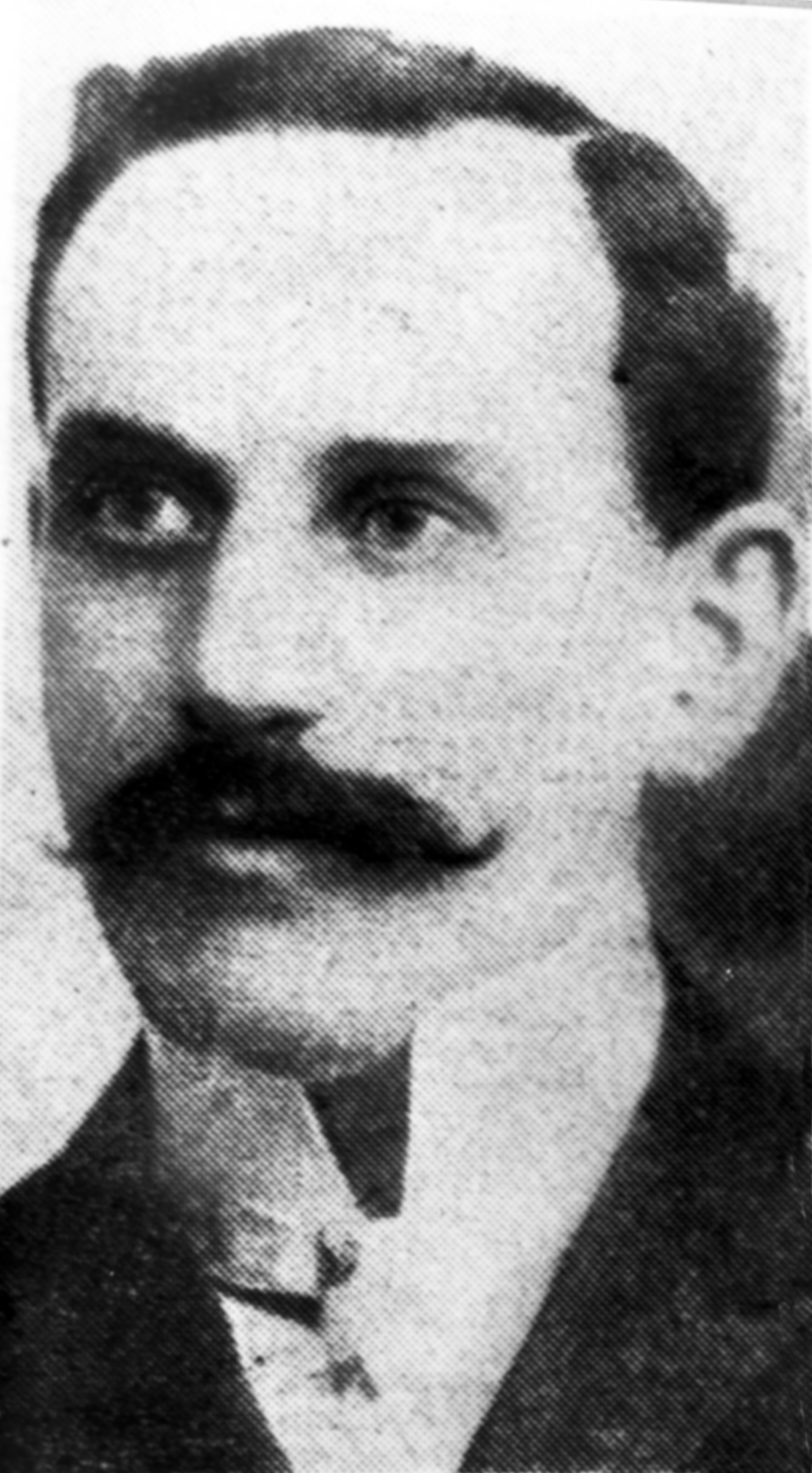

Yet, while George Ochs thrived in his role at the Times, he chafed under his older brother's shadow. Determined to earn a name for himself, George entered local politics in the 1890s and won the 1893 mayor's race.

While this decision was greeted with enthusiasm among some local leaders, it did not sit well with his older brother.

"I think he is making a blunder in going into politics," Adolph confided to a friend, adding, "there is nothing but heartburnings and disappointments in such a career to the most fortunate, and a Jew is especially handicapped."

Ochs faced formidable problems when he entered office. The nation was in the grips of the Panic of 1893, a global economic crisis caused by reckless railroad speculation. Chattanooga's problems were compounded by the collapse of the local iron and steel industry, as local mills and foundries were driven out of business by rising Birmingham firms.

Ochs also inherited a city government ill-equipped to deal with this crisis. Like most cities of the day, Chattanooga's government was riddled with patronage, with even minor offices handed out as rewards to political supporters.

On entering office, Ochs and his supporters took immediate steps to reform city government. His first act was to survey 100 cities across the country to determine their salaries and policies. He then eliminated unnecessary offices, consolidated others and aggressively attacked the city's debt. He also resisted calls for political favor, alienating, for example, Catholic voters by refusing calls for public support of parochial schools. Ochs took steps to assist the city's unemployed, establishing a sawmill and laundry to provide relief work and instituting public works projects to create much-needed jobs.

Ochs served two consecutive terms as Chattanooga's mayor and, in just four years, achieved impressive results. His administration eliminated the city's floating debt, reduced the bonded debt and cut the municipal workforce by half. He initiated a number of city improvements, including a new city hall, high school, auditorium, hospital and jail. He extended city streets and sewers and instituted public health reforms that helped reduce the mortality rate by 15 percent. He achieved all of this without raising city taxes.

Ochs received widespread praise for his reforms, and other cities urged adoption of his "Chattanooga Plan."

Though unanimously nominated for a third term as mayor in 1897, Ochs declined and instead rejoined his brother's expanding publishing empire, managing company newspapers in Philadelphia and editing Modern Times, a New York Times-owned magazine.

His political life behind him, George Ochs left Chattanooga, having steered the city through a major economic transition and establishing a model of effective and compassionate government for the Southeast and the nation.

Dr. Tim Ezzell is a research scientist at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, where he teaches in the political science department. Dr. Ezzell is the author of "Chattanooga, 1865-1900: A City Set Down in Dixie." For more information, visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org or call LaVonne Jolley 423-886-2090.