Fifty years ago today, the United States Air Force made its first strike against North Vietnam in what would become known as the Vietnam War. The 50th anniversary of the start of the ground war is exactly one month from today.

By that first strike, two Chattanooga area servicemen already had died in the controversial conflict that would roil the nation for 10 more years, greatly affect two United States presidencies and leave lifelong physical and mental scars on thousands.

Between 1963 and 1971, 57 Hamilton County residents would die in the war. Unless you're a member of one of the families, their names are not widely known, their sacrifice not marked.

Local, state and national projects are afoot to recognize that sacrifice.

On Thursday from 6 to 7:30 p.m. at the Chattanooga Public Library, relatives and friends of each of the 57 service members are invited to come, bring a photograph of their loved one to be scanned and to record their memories about him with local members of the Chief John Ross Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution and Girls Preparatory School (GPS) students.

"They're not forgotten to the families," said Linda Mines, Hamilton County historian and a teacher at GPS. But many people today are "so far removed from this ... conflict."

Telling the stories, she said, "will connect this generation with that generation" and "keep the conversation going."

Photos and memories also will be forwarded to Nashville, where they will become a part of "Tennessee Remembers: Vietnam Veterans," a program of the Tennessee State Archive, and where the photos will hang as part of a "Faces of Valor" display in the Tennessee War Memorial Building.

The effort to collect the photos was begun by state Sen. Mark Green, R-Clarksville, a former U.S. Army Special Operations flight surgeon.

Tennessee is the first state legislature in the nation to launch such an effort, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund.

"It's finally time to do [this]," state Sen. Todd Gardenhire, R-Chattanooga said, referring to the honorable service of service personnel in a controversial war. "It's a chapter that needs to be closed."

The photos also will be sent on to the online Faces Never Forgotten program that is part of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. That organization is currently raising fund to build the Education Center at The Wall, which would be a repository of such photos and memories.

Plans also have been discussed for a local Vietnam memorial, perhaps as part of a renovated Patten Parkway, Mines said. Although the Chattanooga National Cemetery has a small marker and Veterans Park in Soddy-Daisy has a Vietnam-era Huey helicopter, "there's nothing unified anywhere that acknowledges the service and sacrifice of these men."

Following the controversial war, and its political ramifications, it would have been difficult to find consensus on such a memorial, she said. "But none of that has to do with the young men who sacrificed their lives and their willingness to serve."

Friends and family members at Thursday's gathering will have an opportunity to offer suggestions about what kind of local memorial they'd like to see, Mines said.

Contact staff writer Clint Cooper at ccooper@timesfreepress.com or call 423-757-6497.

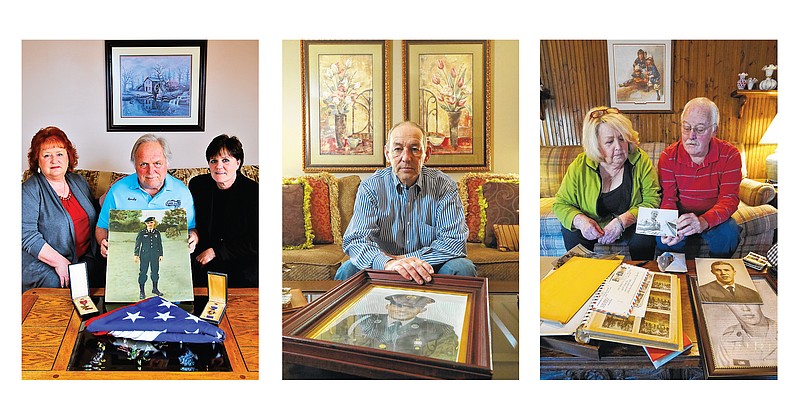

(Stories of three of those local veterans are below.)

'Loved fast cars'

Ray Clark will always be 21, according to his sister, Melanie Clark Crabtree.

"I can close my eyes and see him smiling," she said of her brother, who died in Kieh Hoa, South Vietnam, on Oct. 23, 1968. "He died when I was 14, and now I'm 60. When you die young, you're always young. I guess you're immortalized."

Clark was the oldest of four children, who moved with their parents from Maine to Chattanooga in 1962. The family settled in Pin Oak Heights, and Clark graduated from Brainerd High School in 1965.

"He was the best big brother ever," said Melanie. He was always kind to us and our friends. He kept a really close eye on us. He was very protective."

Ray was like their mother -- "kind, quiet, determined, just a good person," she said.

"I miss him harassing me," said his brother, Randy Clark. "He was a prankster, and I was the butt of a lot of those pranks. I'd love to be it again."

He was "a fun, fun, fun person," said his sister, Heidi. "He loved fast cars" and had a silver 1967 Corvette with a black stripe that Randy acknowledged "would fly." He drove it so fast on a trip to Mississippi with their mother, she once related, that she had to continually look out the side window because she couldn't bear to look straight ahead.

"Had he survived that horrible war," said Melanie, his career might have involved building cars or racing cars. "He liked to go fast."

Ray, who volunteered for the military rather than being drafted, attended Airborne Rangers school and had been commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Army Special Forces when he arrived in Vietnam on Sept. 22, 1968. A month later, he was gone.

Family members aren't certain what happened, but they were told he'd been on a rescue mission, that he had flown to pick up some troops when his men were ambushed.

An unclassified action report on the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial Association says this: "The fighting broke out at 1020 hrs when Helicopters carrying Alpha Co, 3/60th Infantry hit a Hot Landing zone One Infantryman was Killed (Lt. Clark) and a Helicopter Pilot was injured in this first attack as the slicks moved in to land the Troops in the area."

"He'd gone back for one of his men," Heidi said. "He was shot in the head. They said he'd been in charge."

"[Their parents] kept a lot of the grisly details from us," Melanie said. "It still is really hard to talk about."

Clark was awarded the Purple Heart, Bronze Star and National Defense, Vietnam Service and Vietnam Campaign medals.

He had been engaged to be married when he was killed, one of his sisters said.

"Somebody with that much presence," said Melanie, "I don't know how you say good-bye."

'An A-No. 1 kid'

"Trust me, when you see two military men coming to your front door, words can't explain the feeling," Al Slater said, "because you know what they are coming for."

On that day, as December 1966 was about to become January 1967, they'd come to tell Slater and his wife, Jane, that her brother, Randall Hixson, had been killed in Vietnam.

Moments before, the men had been at Jane Slater's parents' house 100 yards down the street, breaking the news about their 20-year-old son to them. They'd also been to the home of his widow, Connie, to inform her.

Pfc. Hixson had been in Vietnam 10 days and had been married about two months.

"Train 'em and send 'em," said Slater. That, he said, was how it went back then.

Hixson had grown up in Soddy-Daisy, moved with his family to Norfolk, Va., where his dad got a job, and eventually moved back with them. He completed his senior year of high school at Soddy-Daisy, where he played in the annual Tennessee-Georgia all-star football game, won the sportsmanship trophy and was remembered as the team's best defensive back. He also was captain of the track team and could "hit [a golf] ball a mile."

Off the field, the middle of five children was a student leader, a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and active in the youth group at Mile Straight Baptist Church.

"He was a good kid, very well respected," said Slater, who'd known his brother-in-law since he was 8 or 10. "He had high morals, went to church regularly. He was an A-No. 1 kid."

Hixson's younger -- by three years -- brother, Gary, looked up to him as a "role model and best friend."

"We spent lots of time together," said Gary, the youngest of the siblings. "Both of us loved sports. He was easygoing, athletic, mild-mannered, kind and respectful to everyone he came across. I don't remember that he ever said a cross word to anybody, except maybe me, and I probably deserved it."

After high school and before being drafted, Hixson worked at DuPont.

His likely plan, Slater said, was to "fulfill his duty and be a good solider" and probably have a job waiting for him at DuPont when he returned.

Then came the evening of Dec. 27, 1966, when the young radioman's unit got overrun by North Vietnamese forces. In a foxhole in the midst of a mortar attack, he was killed instantly when a shell landed "right in there with them."

"They try to take out communications first," Slater said.

An Army buddy from Coalmont, Tenn., who was there when Hixson perished came by some months later and provided the family more details than they knew up to then.

He was buried at the Hixson-Foster Cemetery in Middle Valley after what his brother-in-law said was a "rather impressive military ceremony."

His widow, Slater said, never remarried.

'A free spirit'

Freddie Long was born on the kitchen table of the home in which he grew up in Ooltewah and died on a road grader while trying to clear a path for his fellow soldiers -- who were saved because of his death -- in Vietnam.

In between, said older brother Eddie Long, he was a "free spirit."

"If there's ever been a free spirit," he said, Freddie was it. "He was always happy, never a down moment."

Long was the youngest of 11 children, the youngest of five of his two parents.

Eddie and Freddie were the two youngest children, only two years apart.

"Whenever you saw Freddie, Eddie was close by, and vice-versa," the older Long said. "We were together the full time until I graduated from high school in 1964."

Eventually, Eddie was drafted and served in the Army for two years. It wasn't until he'd finished his hitch and was in the car coming home from the airport that his family told him Freddie already had signed up for the Army. They were afraid, he said more than 45 years later, "that I would have re-upped and stayed in Vietnam. They were trying to protect me."

In turn, he tried to protect Freddie with some advice from his days in-country as an electrician in an engineering brigade. His younger brother wanted to be a door-gunner on a helicopter.

"There's not too many jobs for [former] door-gunners," Eddie said he told him. "I recommended he try for [an engineering brigade] and get on heavy equipment."

That's where he was on Dec. 1, 1969, when his grader hit an anti-tank mine. The 21-year-old was making way for several trucks behind him, each one carrying 15 to 18 soldiers. He had 28 days to go in his hitch in Vietnam and already had his papers for his upcoming U.S. station.

"Did I do the right thing or the wrong thing? Eddie wondered about the advice.

He and his siblings also missed out on drinking the second of two beers Freddie brought home on leave when one of his sisters was ill. These were "33" beers -- "pretty potent" ones that cost 40 cents to an American beer's 10 cents -- that were brewed in Vietnam.

The Longs passed around the first one but decided the second one wouldn't be shared until Freddie finished his hitch. Today, it sits with other family memorabilia in Eddie's Apison home.

How horrible is war?

Eddie said he wanted to determine if his brother was in the coffin that was returned to the family but was told there would be no way for him to know.

Freddie, who never married, was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star with two oak-leaf clusters, among other medals.

He was buried beside his father in Ooltewah Cemetery. He was accorded that honor, his brother said, because he was the only one present when his father died.

"If I live to be 100," Eddie said, "I'll still consider him to be a 21-year-old, happy-go-lucky kid."