Of all the stories being told about Pat Summitt, there is also this one:

It was 2007. The Lady Vols, undefeated at the time, were headed into December with four straight home games in Knoxville. In Chattanooga, Laurel Moore Zahrobsky, 35 at the time, was headed back to work from maternity leave.

Then her dad called.

"He surprised us with tickets to see the Lady Vols," she said.

At the time, Laurel, who teaches dance at Girls Preparatory School, and her husband, Frank, were in the diaper years: two children under 5 and a third barely 3 months old.

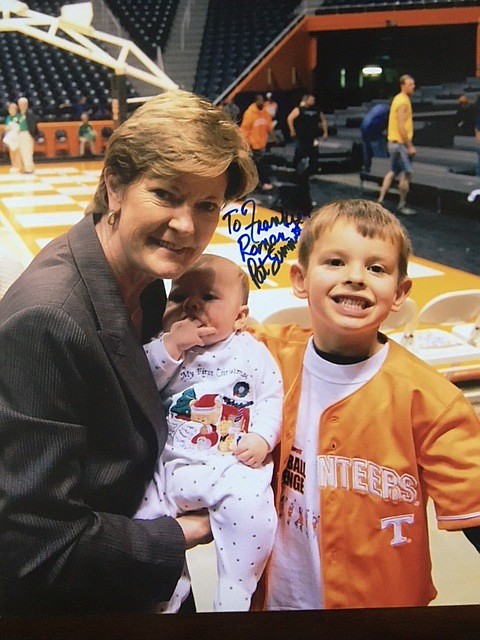

Happy to see the Lady Vols, and also her adoring parents, Laurel packed the bags and took the boys - baby Roman and 5-year-old Frankie - to Knoxville, while Frank stayed behind with Linley.

"Daddy-daughter time," Laurel said.

They had great seats, and sat near a friend who was a sorority sister with Summitt; after the game they went courtside and eavesdropped as Summitt gave interviews; then, Summitt's friend - the sorority sister - shouted: Pat, come meet this family!

"She came over right away," said Laurel.

After handshakes and smiles, Summitt asked to hold baby Roman. (Would Geno Auriemma or Fulmer have done that?)

Roman did what babies often do in moments of great significance.

"He spit up on her," remembers Laurel.

Gracefully, humbly, like a good mom, Summitt laughed, then turned to Laurel. "You have lovely sons," she said. Then, already tired after the game, with her team waiting in the locker room, Summitt continued to asked about Laurel's family.

How old are your kids?

I have three kids under 5, Laurel told her.

Do you also work?

Yes, ma'am.

"Then, she looked at me, with this look," Laurel remembers.

It was not the blue-eyed icy stare Summitt was known for. It was another look entirely.

It was love.

And respect.

One mother to another.

"You're doing a great job as a working mom," Summitt told Laurel. "That is really awesome you can do all that you're doing."

Laurel was speechless.

"Here was the winningest coach in basketball history, and she's telling me I'm doing a good job?" she said.

In the male-heavy American sports world, Summitt was more than just a coach.

She was a woman.

And a working mom.

"Motherhood suited Pat," her obituary reads.

As we eulogize her, we must not forget that Summitt exists as a feminist icon; to celebrate Summitt's athletic success also means to celebrate her gender success - a woman who entered the sport not long after Title IX, who drew an initial salary of $250 a month and washed her own players' jerseys, who coached her first game in front of 50 or so fans, and who later, after all the success, turned down an offer to coach the men's team because to her it was not a promotion.

Summitt's career was not only athletic, it was political. To millions of women, teenaged girls and working mothers, Summitt was more than just a coach; she represented the guts and willingness to smash a (rocky) glass ceiling and perform within the male sports world with athletic fire and maternal love.

She was possibility.

"As we flew around those summer courts, all knee-pads and ponytails and grape Gatorade, we did so believing we were really, truly important - that our game mattered, that we mattered," columnist Kate Fagan wrote in ESPN.

Do you have a daughter who plays basketball? I do. And every time she shoots out in the driveway, or practices toe-to-toe with the neighborhood boys, there exists a thin orange line between her young athleticism and Summitt's career.

"It was Summitt who had earned us much of this; this baseline belief we all grew up with: that we were respected," Fagan continued on ESPN.

We cannot isolate Summitt's success as a coach from her success as a woman and mother. We cannot allow Tennessee lawmakers to eulogize her while also consistently legislating against women's rights. We cannot praise her legacy at a football-heavy Southern university without also being keenly, painfully aware of the continued disparity and sexism within American athletics.

If we love Pat Summitt, we must also love and honor working moms and pioneering women.

"She took the time to recognize that I needed that encouragement," Laurel remembers. "Or maybe she was thinking of her own mom, or thinking of other moms she knows. It meant as much to me as what she would say to her players."

One working mom to another.

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6329.