View other columns by Mark Kennedy

Tom Hunt figures he has owned about 95 cars over his lifetime.

"One of the greatest pleasures in the world for men is trading cars," says Hunt, 84, who walks with a cane and has hung up his car keys because of vision problems.

Hunt telephoned me recently after I mentioned in a column that one of my sons is interested in auto mechanics. Hunt, you see, is of the generation of American men who came of age in the middle of the 20th century and considered building fast cars - aka hot rods - to be their gateway to manhood.

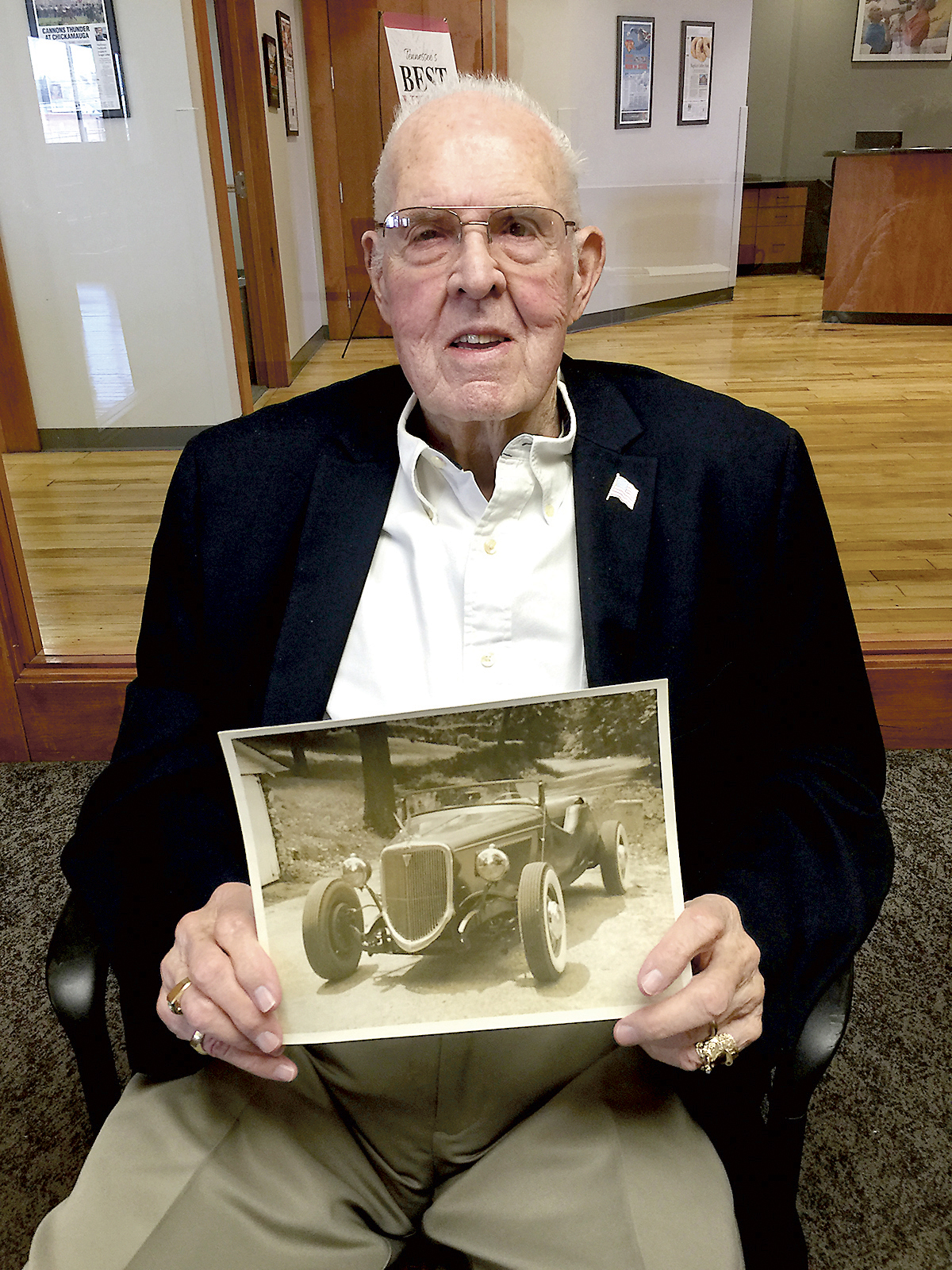

While he was still at Chattanooga High School in the late 1940s, Hunt built a hot rod from a modified 1934 Ford coach he bought for $75, money he had saved from birthday gifts from his aunts and uncles.

Hot rodding, which involves re-sculpting car bodies and swapping out engines, started as a post-Great Depression phenomenon. Returning World War II servicemen accelerated the trend in the 1940s, when chopped and lowered roadsters spawned a whole new automotive culture. The trend's epicenter was California, and Hot Rod magazine was its bible.

As a boy, Hunt befriended the late Charley Card, a Chattanooga businessman who owned a downtown restaurant. The eatery, located near the Read House, was known as a model of efficiency, with fast-paced waiters serving a U-shaped lunch counter with machinelike precision.

Card was a car enthusiast of the first order. He was a leader of the Chattanooga Racing Association, one of the original sponsors of NASCAR and what was then called the Daytona Beach Stock Car Classic.

In 1948, Hunt traveled to the first NASCAR-sponsored Daytona Race and Card took him under his wing. Hunt remembers selling Hot Rod magazines out of the back of Card's car to the Daytona race crowd and collecting names for a new mail-order speed shop business that Card intended to start back in Chattanooga - the first of its kind in the world.

Later, when Card opened his speed shop called "Honest Charley" on McCallie Avenue, Hunt wrangled an after-school job there helping fill mail orders. The mail-order business flourished from the start, and even expanded to include a chain of retail speed stores. (The business still exists today on Chestnut Street under the ownership of the Coker Group, Chattanooga's first family of vintage automobiles.)

Meanwhile, back in the 1940s, Hunt and Honest Charley Card became friends, traveling to stock car races around the South.

While working at Honest Charley's Speed Shop, Hunt began assembling parts for his 1934 Ford coach. He became a junkyard scavenger and a master of trading. At one point, he swapped the '30s-era Ford body on his project car for a 1929 A-Model convertible body.

Soon after he began the 15-month process of piecing together his hot rod, Hunt realized it needed to be moved inside for the winter. His father helped him haul car parts to Cleveland, Tenn., where a 7-Up bottler let him use some warehouse space to work on his car on weekends.

"Soon it dawned on me," Hunt remembers. "I didn't know how to weld. I didn't know how to torch and paint."

In those days the car community was tight-knit, and Hunt found automotive craftsmen willing to teach a smart teen-ager their skills.

When the car was finished, Hunt, then 17 years old, was eager to show his hot rod to Card. On the day of the unveiling, he drove the car to the speed shop and was in the middle of his presentation when a big Buick Roadmaster pulled up, he remembers.

Out popped Bill France Sr., co-founder of NASCAR, and Preston Tucker, automotive designer, entrepreneur and maker of the short-lived 1948 Tucker Sedan.

Tucker immediately took an interest in Hunt's handmade car and did a walk-around inspection.

"You built this car?" Tucker said, clearly impressed.

"Yes, Mr. Tucker, the work is 95 percent mine," Hunt said.

Tucker admired Hunt's work stabilizing the car's exhaust pipes and cutting down the doors, a process called "Frenching."

Hunt eventually served in the U.S. Navy's Seabees during the Korean War, and later became a successful salesman. But his passion for cars never waned.

As for the fate of his original hot rod: "Some rich cat on Lookout Mountain bought it for $1,250 during the war," he says.

His profit? About $1,000, Hunt figures.

Not bad, if you don't count about $20,000 in labor.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645. Follow him on Twitter @TFPCOLUMNIST. Subscribe to his Facebook updates at www.facebook.com/mkennedycolumnist.