John McFalls, 92, wakes up every morning at 6 a.m. at his ranch house off Lee Highway.

He pours himself a cup of coffee, walks his 15-year-old Shih Tzu named Chuck around the block, and then drives across town to visit with his wife, Vivian, who died on Feb. 21, 2014.

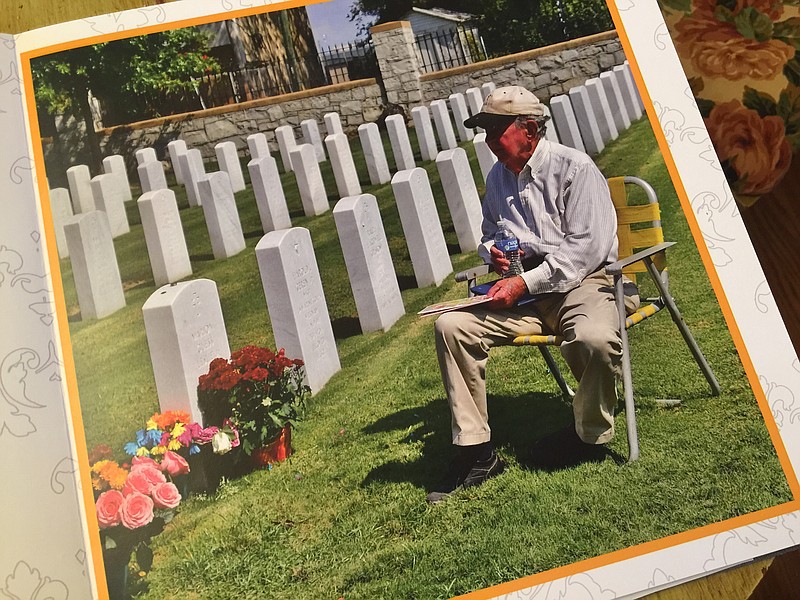

McFalls is a familiar figure to morning motorists on Bailey Avenue, who can't help but notice the sweet old man's daily visits to the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

What most of the motorists don't know about, of course, is the 74-year love story that compels McFalls' daily visits.

"People can't understand why I like to go see Vivian every morning," McFalls said. "Well, we talk. We sing together. We've been doing that for 74 years.

" ... I still think I'm-a looking after her. Is that crazy, or not?"

The workers at the cemetery certainly don't think he's crazy. Hardly a morning passes that one of them doesn't walk over, take off his work gloves and shake McFalls' hand. Sometimes they'll even join him in song, or read scripture while standing alongside plot 390.

"The boys down at the cemetery, they look after me," McFalls explained.

___

John McFalls (who goes by J.) and his late wife Vivian were dirt-poor children of the Great Depression who fell in love as 15-year-olds, married at 17 and loved and cherished one another for more than 70 years before Vivian died of brain cancer four years ago.

Their bond is so strong that McFalls has chosen to ignore the wedding vow imploring newlyweds to stay together "until death do us part." To him, Vivian is still a palpable daily presence in his life. There's no "parting" to it.

To understand this, you must understand where they both came from.

McFalls was the son of a Rhea County sharecropper, the eighth of 12 children born on the cusp of the Great Depression. Poverty was so pervasive back then that people didn't even know they were poor, he said. They barely even knew they were hungry.

Before he dropped out of school after 7th grade, John would come home from his one-room schoolhouse and his mother would give him a pan and tell him to go pick a "mess of wild salad." Other times, his brothers and sisters would harvest walnuts from the woods to survive.

When he was 11, John was "farmed out" to another family as a field worker for 75 cents a day. By the time he was 15, he left home and came to Chattanooga, where he lied about his age and got a job working at a hosiery mill on Main Street.

One day at work, he saw a pretty, 15-year-old girl eating her lunch on a concrete slab. She was taking bites from a sandwich while sipping from an orange soda, which she'd spent her last nickel to buy.

With his rough country manners, McFalls thought nothing of walking up to the young woman, bending over and stealing a sip of her drink.

Unhappy, Vivian Pell gritted her teeth and frowned at him.

No softie, she had lived a hardscrabble life, too, moving 21 times before she was 12 and dropping out of school after 7th grade, McFalls said. They immediately formed a bond.

"And we've been together ever since," McFalls said, refusing to use the past tense.

___

In the early 1940s, John would walk from his dollar-a-week boarding house in Highland Park down to Vivian's apartment on 4th Street (site of a present-day Unum parking lot). Then they would stroll back to Warner Park, where Vivian would lace up her roller skates. They were just children, really, yet both living on their own.

If they were flush - with, say, 75 cents between them - they'd continue their date at a downtown drug store, where they'd split a BLT sandwich and a malted milk with two straws.

In the 1940s, John did what most men of his age did - he got married and volunteered for World War II. He spent two and a half years in the Pacific theater. After the war, John got a job in Ohio making car motors, but Vivian soon begged him to move back South, and after a year the couple returned to Chattanooga.

"When I come back out of the Army, we didn't have anything," McFalls recalled. The two were so poor all their belongings fit into a sack that they slept with at night, he said.

In their quiet hours, Vivian would breathe hope into her husband.

She'd say, "J., one of these days we're going to have a home. We're going to be different. I know where you come from, you know where I come from. But we're going to be different."

John found work at Foundry Pattern Service making patterns for water valves and auto parts. He loved the work, but one day his boss told him that his 7th-grade education made the job unsustainable for him.

"It broke my heart," he said. "I could do things with my hands, but I didn't have anything in my head."

Back home, his young wife wasn't going to let her husband give up without a fight.

"J., you keep pushing," she said. "I'll go back and get my GED, and we'll learn together."

So, that's exactly what they did. A few weeks later, touched by the couples' determination, John's boss told him not to worry.

"He said, 'Go home and tell Vivian that as long as I've got a shop, you've got a job.'"

___

In the 1940s and 1950s, John and Vivian made their contribution to the baby boom generation, welcoming three children in 12 years, two girls and a boy.

Eventually, they made good on Vivian's vow that they would have a permanent home. The couple bought a lot in a 1960s-era subdivision off Lee Highway called Midfield Acres, where the neighborhood motto is "Cooperate, Appreciate, Beautify." The brick ranch house in the suburbs was a stretch purchase for the couple, but John had never seen his wife as proud as the day they moved into that new house.

The next happiest day was a few decades later when Vivian called J. aside and showed him the papers from their paid-off mortgage. The girl who had been forced to moved 21 times by age 12 wasn't going anywhere.

The McFalls pinched pennies, never letting on to their children that sometimes they had to juggle bills month to month. They both agreed that it's impossible to "sacrifice" for their children; providing the best life possible was a joy, not a sacrifice.

At 62, after the children had all left the house, John retired from work.

"I had gotten up for work every morning for 51 years," he said. "I just thought it was time."

The couple settled into retirement with a shared commitment to make one another comfortable. They were different people with different interests, yet they made it work.

John liked to go to bed at 9 p.m. and Vivian liked to stay up to watch "The Tonight Show" and sleep late in the morning. Yet every night they would meet at the kitchen sink before John went off to bed to express their deep love and appreciation for one another.

___

In 2013, when Vivian was diagnosed with a brain tumor, the doctor said she might live a few weeks. Yet she lingered for 11 months.

John refused to admit her to a nursing home and tended to her at home, with the help of some heroic hospice nurses.

In her final days, when she could barely talk, Vivian admonished her husband.

"J., please promise me two things," she said, according to her husband. "Promise me that you won't give Chuck away and that you won't stop being J. Just keep being J."

The day she died, McFalls remembered her last breath.

He counted in his head, waiting hopefully for her to inhale.

10 seconds ... 15 seconds ... 25 seconds

Eventually, he stopped counting.

___

On Sundays, J. McFalls arrives at the Chattanooga National Cemetery with a lawn chair in tow. It's his day to linger at his wife's graveside.

"Sometimes I stay an hour and a half or more," he said. "I sing a song or two. We worship together. Usually two or three people show up and walk over."

View other columns by Mark Kennedy

One Sunday, a woman walked over and started to vent.

"I understand you come here every day," she said, her hands on her hips. "Don't you realize everybody here is dead?"

McFalls turned to the woman and felt his response gathering like steam in his brain.

"Ain't nobody dead here," he said, in no mood to be lectured.

Next, he gestured across the cemetery, where more than 50,000 souls are laid to rest.

"Just look," he said. "Every one of these [gravestones] is a story. It represents a life. Somebody's mamma. Somebody's daddy. Somebody's brother.

" ... Somebody's beloved wife."

___

McFalls' favorite song to sing to Vivian at the cemetery is a 1969 song called "I Love You Because You are You" recorded by singer Carl Smith.

One of the verses goes like this:

"No matter what the world may say about me,

I know your love will always see me through.

I love you for the way you never doubt me.

But most of all I love you 'cause you're you."

___

"She didn't leave," McFalls said. "She's still part of me, and I'm still part of her. There was no space between us. God put us together."

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.