The Brainerd Panthers football team made a decision several days ago to display a black power symbol during the playing of the national anthem before Friday night's football game at Marion County.

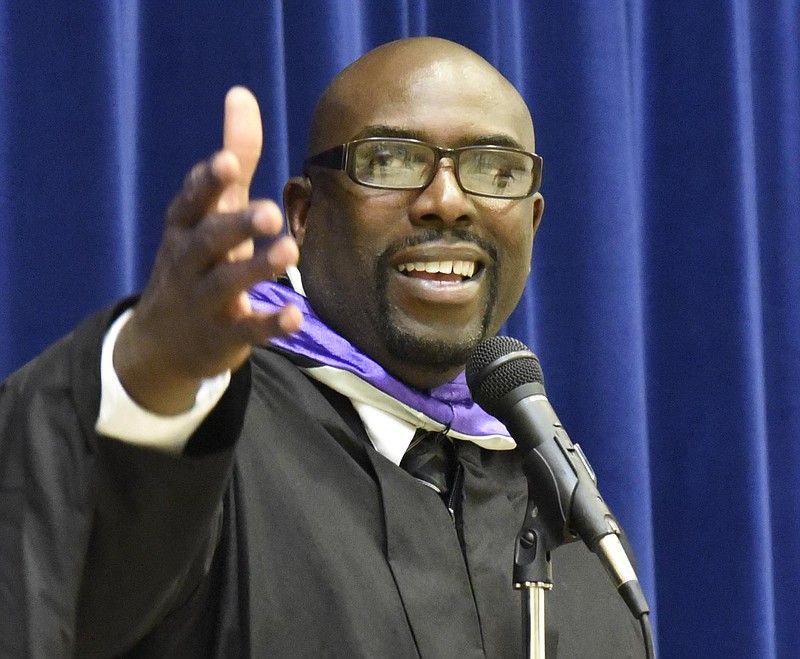

According to the team's coach, Brian Gwyn, who told the Times Free Press he discussed it with his players, the thought was to "make a statement" that "there is still racism in our country, and we need to shed light on it."

The move was meant to be in solidarity with San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who has chosen to kneel during the playing of "The Star-Spangled Banner" before his team's National Football League games this season for what he perceives as racial inequality and police brutality.

The Brainerd team's decision, Gwyn said, was for players to bow their heads and place their closed fists over their hearts as the anthem was played. It was similar to the political demonstration United States track athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos made after winning gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. As the national anthem was played, the athletes turned to face their flags, raised a black-gloved fist and kept it up until the song ended.

On Friday morning, Principal Uras Agee said there would be no protest and that "Gwyn stands alone" in "some of the things that were said." Later Friday, interim Superintendent Kirk Kelly said neither Agee nor Brainerd players knew anything about the idea before Gwyn mentioned it to the Times Free Press.

The Olympics gesture - now 48 years in the rear-view mirror - was a long-remembered demonstration, and that's what Gwyn said on Thursday that he had wanted Brainerd's gesture to be.

"The only way to make change," he said, " is to make sure people are talking about it."

They are talking about it, but many are wondering - like we are - to what end was such a gesture to be.

Forget for a moment what the Hamilton County Schools, school board or state policy may be on protests and what kind of leadership was shown in condoning such an idea.

But just what did Gywn hope to accomplish with a black power symbol? With one in a setting where public prayers are all but forbidden? With one at each game for the rest of the season?

It certainly wouldn't have ended any vestiges of real or perceived racism that he or any team member felt. Racism cannot be outlawed, voted out or scrubbed away. It is a devious product of the mind, and it takes a Grinch-on-Christmas Day-sized open heart to overcome it.

Agee, on the other hand, said Friday that "we have worked very hard on the culture and climate [at Brainerd]."

Indeed, that's the real kind of solidarity that needs to continue to be promoted at the school.

After all, Gwyn probably doesn't need to be reminded Brainerd is on the state's list of high-priority schools - currently the only high school in Hamilton County on that list. He probably is aware that while the ACT scores for all Hamilton County Schools rose 0.2 between 2015 and 2016, Brainerd's ACT scores dropped .5. And Gwyn probably knows that only 1 percent of 2016 graduates at Brainerd scored college-ready on the test.

But test scores and college-readiness are just part of it.

Gwyn has probably heard of the gang problem in the city and that Brainerd students are being recruited hard to join this group or that. Since 2013, according to Sgt. Josh May, focused deterrence coordinator for the Chattanooga Police Department, gangs have been involved in 60 percent of the shootings and 43 percent of the homicides in Chattanooga.

No doubt, the football coach also has knowledge of single-parent households, out-of-wedlock children and drugs involving Brainerd High School students.

By no means is Brainerd the only school with such problems. They cross the city, cross from public to private schools and cross racial lines. But making a black power symbol solves none of these problems.

Unlike racism, though, the other problems can be solved - or lessened, anyway - by making better choices. That doesn't mean it's easy, but it is possible. And solidarity can be part of that. Sports teams have to have solidarity if they want to be successful, right?

Imagine, for instance, if Gwyn and his players determined that, as a team, they would strive for a 2.0 grade-point average by the end of the first quarter of the school year, a 2.5 GPA by the end of the second quarter and a 3.0 average by the end of the third quarter. And that they helped each other achieve that. What if he also challenged them to go without weed and maintain sexual purity, and that some of the players took him up on it.

Just imagine.

Solidarity can be a good thing. Empty gestures rarely are.