The first bill passed by the United States Congress in 1995 subjected members of the House and Senate to many of the same laws to which we average Joes and Jills are subject.

Bravo.

But hidden in the fine print of the Congressional Accountability Act was the establishment of the Office of Compliance, which did practically the opposite of leveling the playing field when it comes to claims of sexual harassment. Under auspices of the independent office, the government pays out taxpayer money to settle sexual harassment - and other - claims and allows little public disclosure of the cases.

Last month, the office, "based on the volume of recent inquiries about settlements reached under the Congressional Accountability Act," revealed the government has paid more than $17 million from a Settlement and Awards Fund over the last 20 years to resolve claims, including for sexual harassment, filed by employees of Congress.

We believe this should end as soon as appropriate amending legislation can be passed by Congress. Under no circumstances should taxpayers be footing the bill for settling sexual harassment claims or having them buried under protective paperwork.

A bipartisan bill, with sponsors including U.S. Rep. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., and U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tenn., seeks to do just that.

It would ban taxpayer dollars to settle sexual misconduct lawsuits, end the requirement of nondisclosure agreements in such settlements involving members of Congress and staff members, nullify existing nondisclosure agreements and force anyone who settled claims of sexual harassment with federal money since 1995 to pay it back.

Last month, Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., introduced similar legislation requiring that lawmakers who settle harassment claims with the Office of Compliance repay the Treasury for their settlements. It also would eliminate mandatory nondisclosure agreements as a condition for entering mediation and require public identification of offices that have settled cases.

The current legislation requires victims of sexual harassment to undergo mediation with their alleged perpetrator and wait up to three months before they can file a formal complaint. In general, though it ostensibly was put in place to prevent operatives from targeting political opponents with bogus claims, it is said to be far more risky for the victim rather than the perpetrator. And interns, who often work for free, are not protected by the law.

Between 1997 and 2017, according to the Office of Compliance, 264 settlements and awards have been made. How many involve sexual harassment charges is not known because the office doesn't break down the numbers. It also pays out claims in cases of religious and racial discrimination, overtime pay disputes, violations of the Americans With Disabilities Act and violations of multiple statutes. And the alleged perpetrators aren't necessarily members of the House or Senate but could be members of the Capitol Police or Capitol maintenance workers.

Speier testified recently that two sitting members of Congress have engaged in sexual harassment but wouldn't name them because the victims don't want them identified publicly. She is barred from identifying one member because of a nondisclosure agreement, she said, and isn't identifying the second at the victim's request.

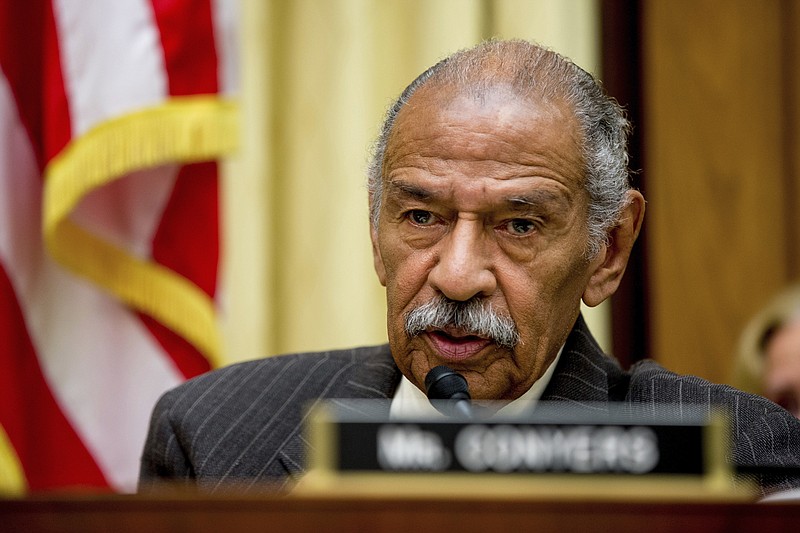

In recent weeks, Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., was accused of forcibly kissing and groping a woman during a 2006 USO tour, and Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., was reported to have paid a woman more than $27,000 from his taxpayer-funded office budget to settle a complaint in 2015 that she was fired from his Washington staff because she rejected his sexual advances.

Franken has apologized for his behavior but faces a likely Senate Ethics Committee investigation, while Conyers has denied the charges - and those of another woman who said the congressman criticized her appearance and attended a meeting in his underwear - and vowed he wouldn't resign, though he did step down from his post as the top Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee. Reportedly, the House Ethics Committee is reviewing his case.

"It's very clear [that] when the original bill that put this process in place was passed in 1995," Speier told Vox, "it was done to protect the institution, not the most vulnerable."

Rep. Gregg Harper, R-Miss., chairman of the House administration committee, said he had fielded no sexual harassment settlement requests since he became head of the committee earlier this year but promised a hearing by early 2018 that would consider "ways to create a respectful reporting and settlement process."

Lawmakers in both parties already seem willing to require sexual harassment training for themselves and their aides, but we hope they won't stop there. The bills sponsored by Blackburn and Cooper, and by Gillibrand and Speier, are bound to have their detractors - perhaps for technical reasons we're not privy to yet - but we hope Congress uses them to look seriously at the shameful practice of having taxpayers finance the settling of harassment claims. The people have a right to know what's going on with those who purport to do the peoples' business, especially when that business is contrary to what everyone concerned knows is morally right.