The pre-eminent Christian evangelist of the 20th century was once told in Cleveland, Tenn., according to one story, that he would not amount to much after quitting Bob Jones University.

Billy Graham, who died Wednesday at the age of 99, told the university president he was withdrawing from the then-unaccredited, evangelistic school after about six months there.

Jones, according to a later version of the evangelist's biography, allegedly told him leaving made him a "quitter" and that he would not be successful. Another version of the story has a not-so-strident Jones telling him that with his mellifluous voice and smooth delivery he still might make something of himself.

By anyone's standards, Graham, often termed "America's pastor," certainly did that.

His messages were heard by hundreds of millions of people across the globe, including 215 million during his more than 400 crusades in 185 countries that began in 1947. Indeed, he preached, according to his evangelistic organization, to more people in live audiences than anyone in history.

Among those, a Chattanooga crusade at Warner Park in 1953 was said to have drawn 300,000 people.

Graham also authored 34 books, and he and his wife, Ruth, received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award Congress can bestow on a private citizen.

The onetime North Carolina farm boy also was listed by Gallup as one of the "Ten Most Admired Men" 61 times, including for 55 consecutive years.

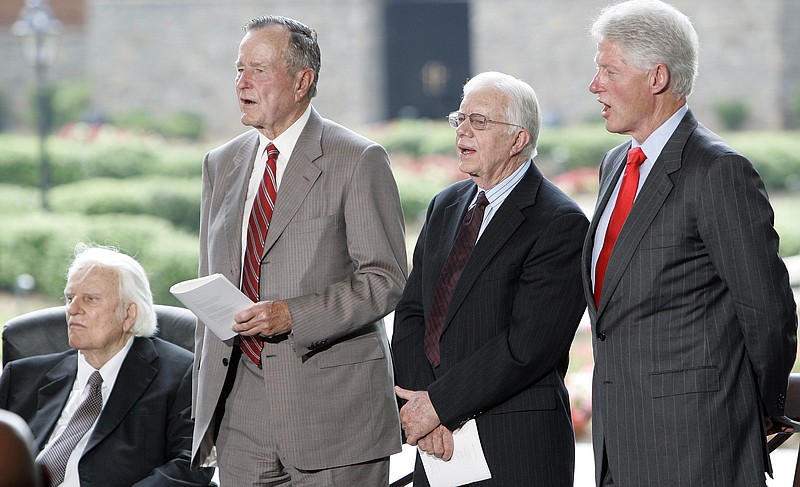

Graham, in addition, was a friend and adviser to presidents and had met or prayed with each one from Harry Truman to Barack Obama.

Former President George W. Bush credited a walk and talk with him at the family's Kennebunkport, Me., home as a younger man with causing him to quit drinking and become more serious about his faith.

With piercing blue eyes, square jaw and flowing blond, then gray, then white hair, Graham had a commanding presence, a sense of humor and a speaking ability that transcended the Elmer Gantry-ism of tent revivalists and lent an aura of studied knowledge to a simple faith.

When Graham told members of the crowd at the end of his messages to "come forward" and that their "buses will wait," they believed him and came, as the mass choir sang "Just As I Am, Without One Plea," many later saying it was their first connection to the Christian faith.

"This is not mass evangelism," he often said, "but personal evangelism on a mass scale."

Graham also was accessible to many because, while Southern Baptist with a Reformed Presbyterian background, he didn't proclaim a hard and fast denominational bent.

In fact, according to the evangelist's historians, he preached his first sermon while attending Bob Jones University at Charleston (Tenn.) Methodist Church and his second at Antioch Baptist Church on Chattanooga Pike.

Graham also didn't dwell on the particular red-meat concerns of the day, whether - as the country grew more secular - it was co-habitation, abortion or gay marriage. Instead, he stuck to his calling.

"I'm just going to preach the Gospel and am not going to get off on all these hot-button issues," he said. "If I get on these other subjects, it divides the audience on an issue that is not the issue I'm promoting. I'm just promoting the Gospel."

Opposed to segregation before the civil rights era, Graham was praised by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who said his own "work in the civil rights movement would not have been as successful as it has been" without Graham.

His 1953 crusade at Warner Park, in fact, often has been cited as the first such intentionally integrated event.

"In Chattanooga, Tennessee, back in 1953, we began insisting that our meetings be purposely mixed," Graham wrote in his syndicated newspaper column "My Answer" on Feb. 25, 1974. "I took this stand before the Supreme Court decision of 1954 and before I had ever heard the word 'integration.'" That Supreme Court decision, Brown vs. the Board of Education, declared segregated schools unconstitutional.

According to biographers, the evangelist arrived early at the field house on March 15, 1953, to tear down the ropes that separated the white and black sections. Even when the head usher resigned after the action, he did not back down on his desire to hold an integrated campaign.

"You stay in the stadiums, Billy," King later told him, according to a 1997 autobiography, "because you will have far more impact on the white establishment there than if you marched in the streets. Besides that, you have a constituency that will listen to you, especially among white people who may not listen so much to me."

Graham did more than preach the grace and saving power of Jesus Christ, though. He lived it.

Though charismatic as a speaker, he was humble in person and devoted to his wife. He never got caught up in the various scandals that other evangelistic leaders found themselves in, and he was quick to cite his own faults, admitting to not being home enough for his five children when they were growing up, for not doing enough for civil rights and for being unswervingly supportive of former President Richard Nixon during his Watergate misdeeds.

"I despise all this attention on me ... I'm not trying to bring people to myself," Graham said, "but I know that God has sent me out as a warrior."

So a warrior he was, a warrior for God, a warrior who always knew his real place in Creation.

"My home is in Heaven," Graham once said. "I'm just traveling through this world."