Each year, a publication called Medscape creates a portrait of the medical profession. It surveys thousands of doctors about their job satisfaction, salaries and the like and breaks down the results by specialty, allowing for comparisons between, say, dermatologists and oncologists.

As I read the most recent survey, I was struck by the answers from orthopedic surgeons. They are the highest-paid doctors, with an average salary of $443,000 in 2015 (which was almost the exact cutoff for the famed top 1 percent of the income distribution).

Yet many orthopedists are not happy with their pay. Only 44 percent feel "fairly compensated," a smaller share than in almost every other specialty.

I know that many orthopedists have a different view: They take pride in helping patients and feel fortunate to enjoy comfortable lives. But despite those doctors, it's clear that orthopedics suffers from a professional culture that does not live up to medicine's highest ideals. Too many orthopedists are rich and think it's an injustice that they're not richer.

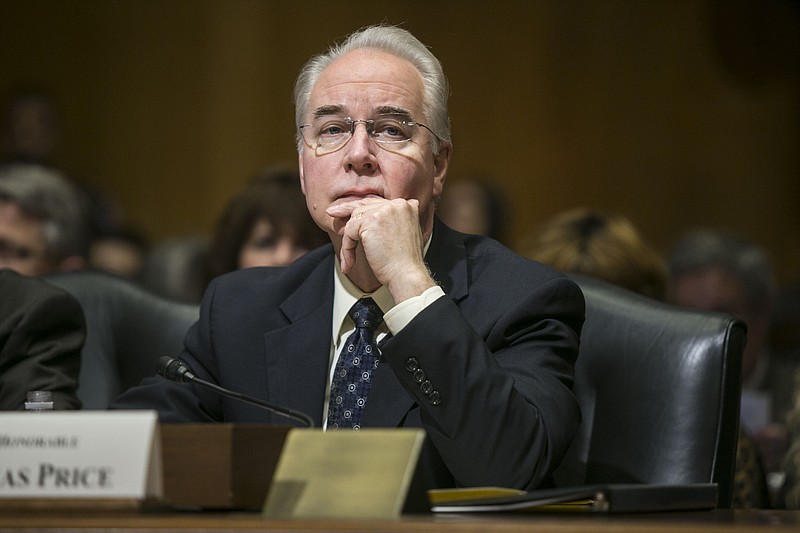

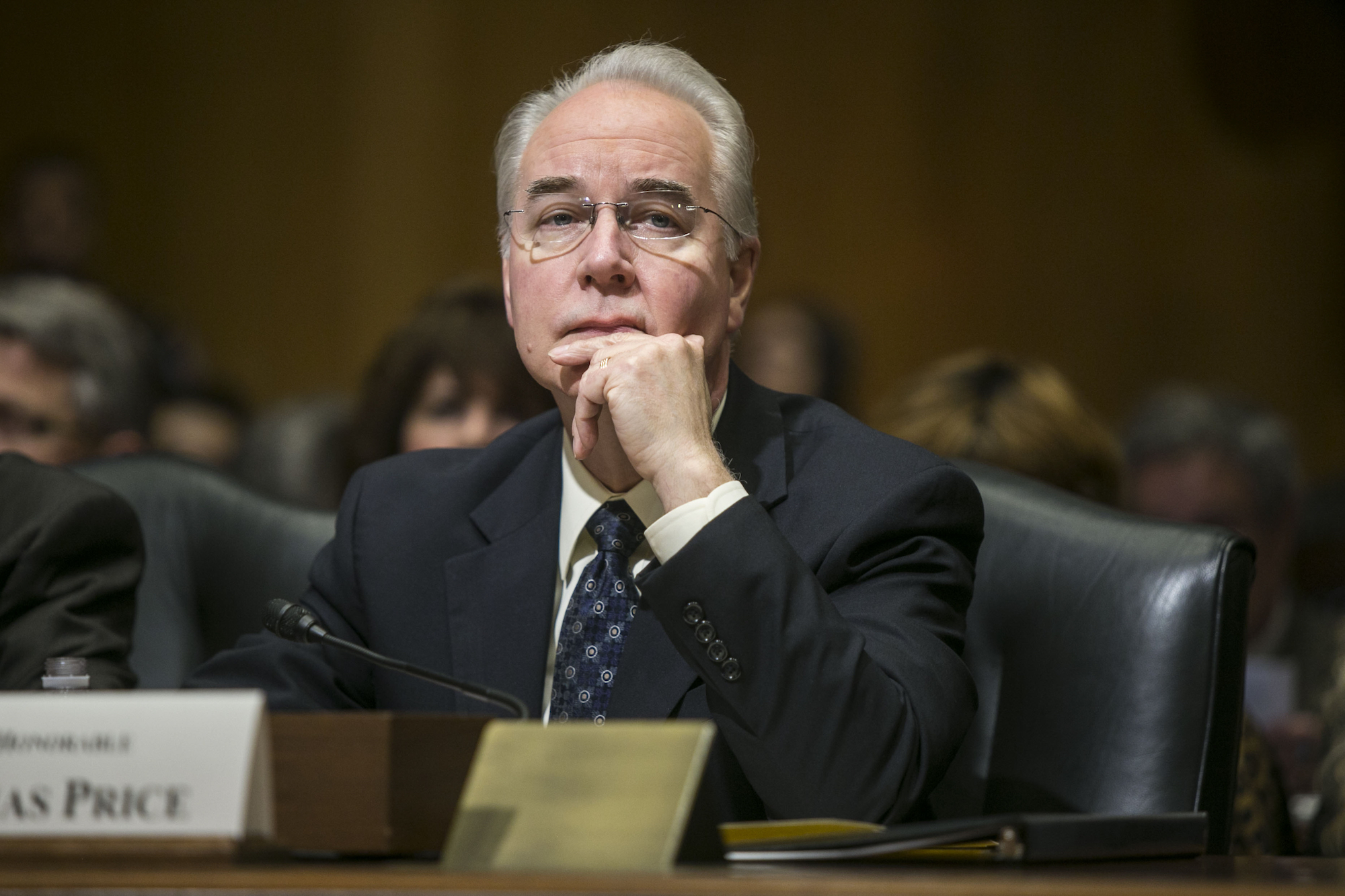

This culture helped shape Dr. Tom Price, the orthopedic surgeon and Georgia congressman who is Donald Trump's nominee for secretary of health and human services.

Price had a thriving practice near Atlanta before being elected to Congress in 2004. His estimated net worth of more than $10 million (and possibly a lot more) makes him one of the House's wealthier members.

Yet he hasn't been content to make money in the standard ways. He has also pushed, and crossed, ethical boundaries. Again and again, Price has mingled his power as a congressman with his desire to make money.

Last March, Price announced his opposition to a sensible Medicare proposal to limit the money doctors could make from drugs they prescribe their patients. The proposal was meant to reduce doctors' financial incentives to prescribe expensive drugs.

One week after Price came out against the proposal, he bought stocks in six pharmaceutical companies that would benefit from its defeat, as Time magazine reported. At the time, those same companies were lobbying Congress to block the change. They succeeded.

It's a pattern, too. Price has put the interests of drug companies above those of taxpayers and patients - and invested in those drug companies on the side.

Price also accepted a special offer from an Australian drug company to buy discounted shares, as The Wall Street Journal and Kaiser Health News reported.

He told the Senate that the offer was open to all investors, although fewer than 20 Americans actually received an invitation to buy at the discounted price. The stock has since jumped in value, and Price underreported the worth of his investment in his nomination filings. It was a "clerical error," he says.

Even without any larger context, his actions are disqualifying. He's repeatedly placed personal enrichment above the credibility of Congress.

But of course there is a larger context. Price has devoted much of his political career opposing expansion of health insurance. His preferred replacement of Obamacare would reduce health care benefits for sicker, poorer and older Americans.

His views have a long history within the medical profession. For decades, doctors used their political clout to help block universal health insurance. They offered many rationales, but money was the main reason. Many doctors feared that a less laissez-faire health care system would reduce their pay.

It's to the great credit of today's doctors that they have moved their lobbying groups away from that position and helped extend insurance to some 20 million people. They understand that some principles matter more than a paycheck.

Or at least many of them do.

The New York Times