WASHINGTON - One of the most satisfying moments in any spy thriller is when the bad guy - the black-hat operative who has been killing and tormenting his adversaries - does something dumb and gets caught. That's essentially what's been happening recently with Russian President Vladimir Putin's pet spy agency, the GRU.

What's fascinating about the GRU revelations is that they seem to reflect an aggressive pushback after several years in which Putin (chiefly through the GRU) launched recklessly aggressive covert actions against the West. The West is retaliating (at least in part) with public information that blows GRU covers and operating methods and, frankly, makes them look clumsy and incompetent.

Those disclosures are the latest in a string of disasters for the GRU, a military spy service known for its panache and daring. Now, we should add sloppiness to that list of operational trademarks. The GRU's spycraft occasionally looks closer to TV's Maxwell Smart than John le Carre's vaunted fictional spymaster, Karla.

The latest expose of the GRU's not-so-secret tradecraft came last Tuesday, when a British investigative group shredded a layer of the lies surrounding Russia's attempt to poison former agent Sergei Skripal in March. It was the equivalent of the tough guy in the trench coat getting caught with his undershorts around his ankles.

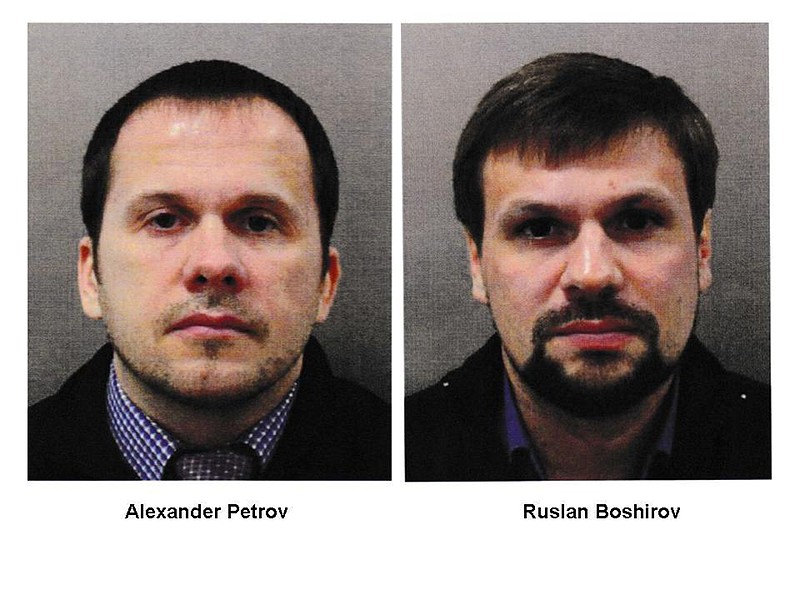

Bellingcat, as the group calls itself, presented photographic evidence showing that a suspect in the Skripal attack, who the Russians had claimed was a tourist named Petrov who worked in the sports nutrition business, is really a GRU doctor named Alexander Mishkin. Last month, Bellingcat had exposed another suspect, whose cover identity was "Ruslan Boshirov," as GRU Col. Anatoliy Chepiga.

The most detailed exposures of GRU tradecraft came in a Justice Department indictment that was unsealed Oct. 4, in tandem with supporting statements from Britain and the Netherlands. The indictment, which named seven GRU officers, included details about Russian spy operations that could only have been collected by the CIA and National Security Agency and its foreign partners.

The dry pages of the indictment reveal tradecraft secrets that could animate a half-dozen spy novels. The GRU operatives used spoof websites to "spearphish" victims into revealing login information (creating a "westinqhousenuclear.com" site, with the misspelled "q," for example). They made payments in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. (Weren't those supposed to be untraceable?) They used malware tools with names like "Gamefish," "Chopstick" and "X-tunnel." They dumped their hacked information by sending direct messages on Twitter to 116 reporters and exchanging emails with 70 journalists.

For the last few years, the CIA, NSA and FBI have watched as hackers and whistleblowers (perhaps with a helping hand from Moscow) revealed the agencies' hacking techniques. For U.S. intelligence officials, revenge is a dish best eaten cold.

The implicit message in all of this: If you hit us, one of the ways we will retaliate is by exposing your operatives, sources and methods. There are other reprisals underway, but these public disclosures undermine the GRU's operational capabilities. And they must make the Russian spy service wonder: What else do the Americans and their allies know? If agent A is blown, then what about his colleagues B, C, and D.

The CIA and its foreign allies don't normally like to reveal secrets like these, because they reveal how much they know about their adversary. The revelations are a public warning to Putin: Knock it off, you're more vulnerable than you think.

Washington Post Writers Group