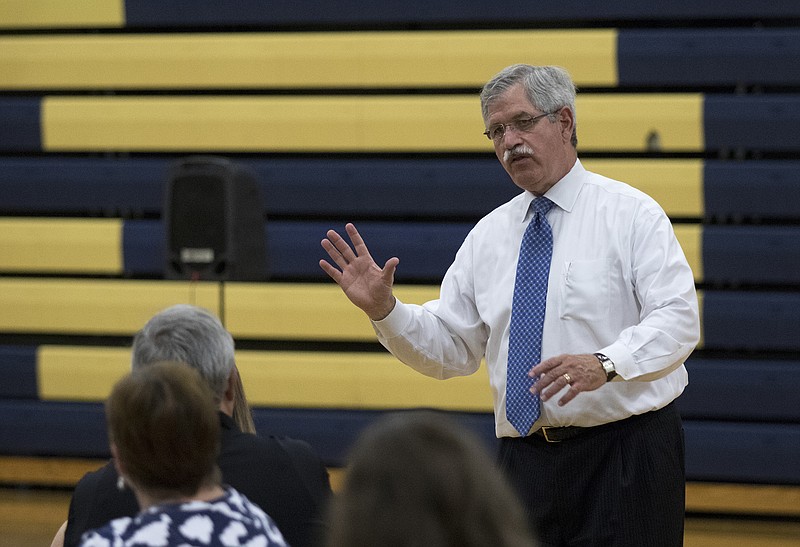

Hamilton County Schools Superintendent Rick Smith has been preaching the gospel of school funding now for weeks.

He makes a strong case for upping the school system's $345 million a year budget by $34 million to total $379 million.

The extra money would go toward a 5 percent raise for teachers and staff, art and foreign language teachers in every elementary school, more graduation options for students and critical maintenance costs, for starters.

Read more

* Hamilton County school board delays vote on 'mind-boggling' list of fees * Hamilton County Schools' budget requests spark challenges

Smith is on the circuit with good reason: Nearly 60 percent of county third-graders read below grade level; only 15 percent of local graduates are college-ready and nearly 65 percent of those who graduate do not go on to college classes.

There's one catch. The increase would most likely require an estimated 40-cent property tax increase, raising the tax rate to $3.16 per $100 of assessed value which would in turn add about $150 a year to the tax bill of a $150,000 home.

Hamilton County commissioners on Wednesday gave Smith's message a chilly reception.

"I'm just not convinced that the monies requested will have the return that I'm looking for," said Commissioner Tim Boyd, who represents the East Ridge area.

"I'm not there, yet," Alton Park Commissioner Warren Mackey said.

"I am supportive of the schools, but give me something to support," said Brainerd Commissioner Greg Beck.

Commissioner Joe Graham, who represents the Lookout Valley area, accused the school district of "hoarding" money with a fund balance of $49 million. Never mind that the schools savings fund -- roughly $34 million, excluding restricted money assigned to specific purposes like federal food service money -- is about 8 percent of its budget and would cover only about four weeks' expenses.

In reality, all those comments amount to little more than posturing among people who don't want to address the real issue. We have nickel-and-dimed ourselves and our children into a dark and lonely corner with too little attention, too few books, too few teachers, too few computers and out-dated teaching methods -- things that, yes, money can buy.

Certainly raising education funding would likely require a tax increase, but it's important to remember that county commissioners and the county mayor invented the pattern of consistently opting to "hoard" money in something they euphemistically call "the rainy-day fund." At the moment, that county fund has about $112 million. Just sitting in the bank. Neither learning nor teaching nor policing or doing anything for the citizens of Hamilton County.

The county mayor and some commissioners in years past have argued that the rainy-day fund makes it possible for the county to have a good credit rating and borrow money cheaply. True enough. But the county had the same good credit rating years ago with slightly more than half this much money languishing around.

It's also true that increasing the school budget is not a one-time, one-year endeavor. It's a recurring expense, meaning that using savings from anywhere is not a long-term solution. It would, sooner or later, mean the county would have to find more revenue -- probably with a tax increase.

Still, using some of the money we already have in our public coffer could take some of the sting out of a tax increase this year. More importantly, had we not been so keen on building a monument of money for the past decade or so, it's entirely possible that we might not be facing this academic crisis.

And it is a crisis.

A study just released at the American Educational Research Association convention in New Orleans finds that a student who can't read on grade level by third grade is four times less likely to graduate by age 19 than a child who does read proficiently by that time. Add poverty to the mix, and a student is 13 times less likely to graduate on time.

"Third grade is a kind of pivot point," said Donald J. Hernandez, the study's author and a sociology professor at Hunter College, at the City University of New York. "We teach reading for the first three grades and then after that children are not so much learning to read but using their reading skills to learn other topics. In that sense if you haven't succeeded by third grade it's more difficult to [remediate] than it would have been if you started before then."

Back here in Hamilton County, that means 60 percent of our third-grade students are in danger of not graduating high school.

Tell us, commissioners, how does a prospective six in 10 high school dropout rate look for present and future industrial recruitment?

Here in Hamilton County, we should perhaps think of ourselves collectively as third-graders on the pivot point.

We can keep on nickel-and-diming our children in public schools while private schools groom the elite to move away, or we can make up our minds to build a Chattanooga workforce that matches this city's potential.

This year more than ever, it is the members of the Hamilton County Commission who will determine greater Chattanooga's fate.