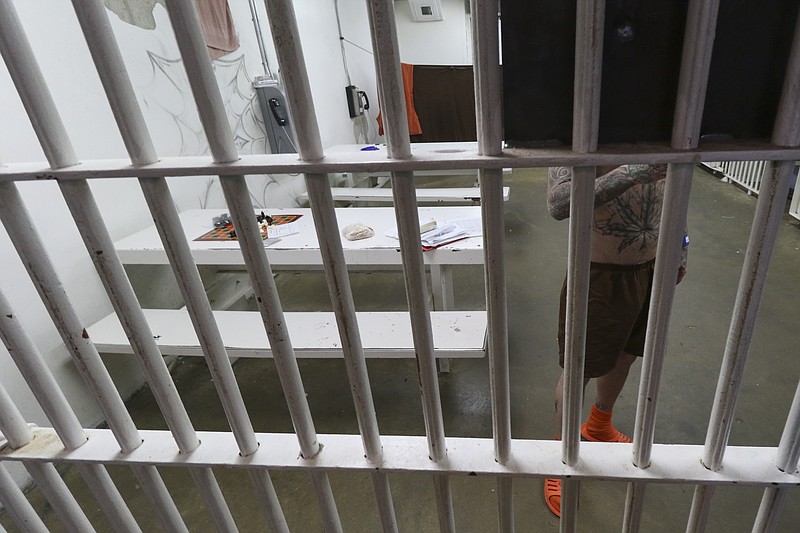

The Hamilton County Commission has two major functions - overseeing the taxpayers' money spent for education and overseeing the taxpayers' funding for public safety and the county jail.

Commissioners recently raised county property taxes to improve both school facilities and the jail.

On Wednesday, Hamilton County Sheriff Jim Hammond brought commissioners a plan to save money in the jail and a request for $25,000 in matching money to flesh out that plan.

Commissioners are expected to vote next Wednesday on the sheriff's request, and we think they should approve it.

Hammond, who has been sheriff since August 2008, has often rightly said the county jail is as much mental health hospital and homeless shelter as it is a place of correction. As many as 40 percent of inmates there are on psychotropic drugs, and a large share are mentally ill or addicted.

After forming a team and seriously studying the problem for more than a year, Hammond wants the county to emulate a plan adopted in Charlotte, N.C., to get mentally ill and addicted people out of jail and into an environment offering supportive housing and a full range of treatment and services.

Moore Place, opened in 2012 as an 85-bed apartment building with an around-the-clock staff of nurses and psychiatric support. Its resident group, on average, had been homeless for seven years. After two years, 81 percent of the residents were still housed. Their average incomes rose 76 percent, mostly from Supplemental Security Income, and 72 percent were on Medicaid. Though 98 percent had health problems and nearly half had three or more medical conditions, their number of ambulance trips, ER visits and hospitalizations was down and their overall health was better. They also saw a 78 percent reduction in arrests and and 84 percent reduction in days spent in jail.

But here's the dollars-and-cents kicker: It saves taxpayer money. Hammond told our commissioners that Charlotte and Mecklenburg County saved $2.4 million the first two years of the program there.

The average daily cost for an individual housed in a residential unit at Moore Place in 2012 was $29.50 compared to a night in jail, which costs taxpayers at least $110 per night, or a visit to the emergency room which carries a price tag of $1,029 per visit, according to CLTBlog, a Charlotte online publication.

Charlotte's Urban Ministry Center, which helps manage the program, put it another way on its website: "The average community cost of a chronically homeless person is more than $39,000 per year in shelter, hospital, ER and jail costs - all of which serve only as band aids. ... We can provide stable housing and case management to this same individual for $13,983 annually and have positive outcomes in health, sobriety and stabilization. In short, permanent supportive housing saves lives and saves our community money."

Hammond offers his own Hamilton County set of numbers for a sobering contrast.

"Just seven users we picked up at random over the last five years have spent more than 4,000 days in jail at about a $420,000 cost to the county, and none of them are any better off than they were ...," Hammond said.

The sheriff says Hamilton County's $25,000 would match similar donations from BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee and CHI Memorial. With that $75,000, the team will begin working with consultants to explore and shape an alternative system here for at least some of the 600 county jail and Silverdale inmates who could be identified as mentally ill, Hammond says.

Hamilton County's jail problem, like that of the nation's, began years ago with consistent reductions in federal and state funding for mental health institutions and treatment facilities. Those reductions forced local jails and correction facilities to become the largest mental health hospitals in the country.

Clearly, criminalizing and incarcerating the mentally ill for minor crimes are not the answers.

In Hamilton County, we don't yet know what the right answer will be, but we certainly know that what we're doing isn't working.

We've gambled before on alternative justice and court ideas - like house arrest programs, Hamilton County Drug Court and Hamilton County Mental Health Court. Most have worked, and those that didn't were tweaked to improvement or eventually abandoned.

Hamilton County commissioners should grant this modest $25,000 request. It could result in better treatment of the mentally ill, as well as much improved efficiency in our jail and workhouse.