At 2 p.m. today, weather permitting, the University of North Carolina will say its final goodbye to its beloved late basketball coach Dean Smith at a public service inside the giant gym that bears his name.

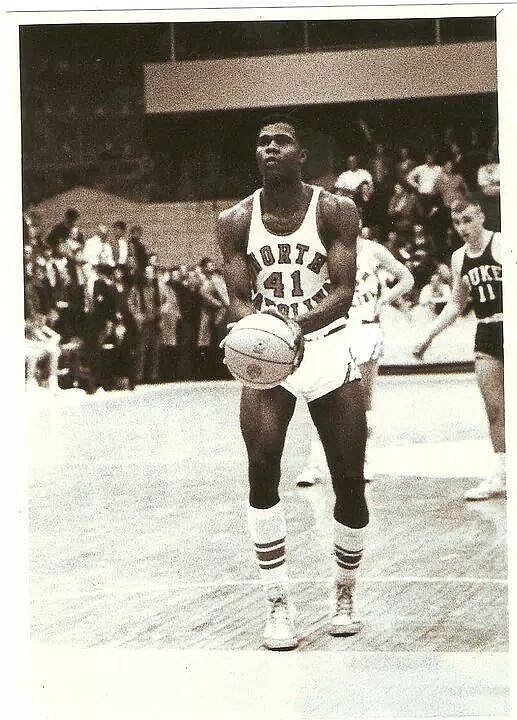

And as the program unfolds, there's almost certain to be more than one reference to Charlie Scott, who many believe to be the first black basketball player in UNC history, and perhaps the biggest key to Smith's first two Final Four runs.

"Charlie Scott was the first black scholarship player at North Carolina," Willie Cooper said the other evening from his Chattanooga home. "But I was the first black player."

The 69-year-old Elm Hill, N.C., native noted that with neither bitterness nor pride. Merely a statement of fact. In the spring of 1964, having just played a major role in 72 straight victories and back-to-back Class AA state titles for all-black Frederick Douglass High School, Cooper was encouraged to become a Tar Heel walk-on.

"(Cooper) was the one we wanted," Smith told the Raleigh News & Observer six years ago in recalling the 6-foot-2 forward known for his disruptive defensive skills.

Yet Cooper says it wasn't quite that simple.

"The storyline at that time was that the school couldn't sign black in-state players because they couldn't score high enough on the (SAT) entrance tests," he said. "I've always heard that Dean Smith called my high school coach, Harvey Reid, and said, 'I need somebody who can get in Carolina.' Coach Reid reportedly told him that he had some good players who probably couldn't get in, but he had another player who wasn't quite as good but who could do the (academic) work."

With that, Smith sent Kenny Friedman, who'd worked under Smith's predecessor, Frank McGuire, and graduate student Reggie Fountain to check out Cooper. Smith also was said to have told them that if Cooper looked as good as the Tar Heels' Bobby Lewis -- who was on his way to an All-America collegiate career -- the coach would offer him a scholarship.

Said Friedman years later: "I saw lots of potential in him. But ... he wasn't nearly as good as Bobby Lewis."

So Smith offered to let Cooper attempt to make the team as a walk-on, with the promise that if he made the varsity as a sophomore a scholarship might arrive.

"I was a 6-2 forward, not a guard," Cooper said. "I was a good player, but I wasn't a ball-handler. Everyone felt I'd make the freshman team, but I had no scholarship."

However, he was the child of a deceased World War I veteran, and "as providence would have it," Cooper explained, "there was a scholarship available for the child of a World War I vet."

The news wasn't immediately positive in his hometown. The Ku Klux Klan chapter in Elm City burned a cross on his foster family's lawn. Yet those foster parents, Martha and Kester Mitchell, had raised 10 children of their own before taking in Cooper. They saw a bigger picture.

"There was an expectation level regarding schoolwork," said Cooper, who was 10 when he moved in with the Mitchells. "They pushed you to do well."

Cooper did everything well. He was president of the student council, played trumpet in the band and worked hard in the school's 4-H Club.

"That's one thing about my father," said his daughter Tonya, who was a two-time TSSAA high jump champion at Ooltewah before going on to play on North Carolina's 1994 NCAA championship basketball team. "He's always stepped up to a challenge. He's determined to succeed in anything he does. Not just get by, but succeed."

By that 1964 summer, Cooper was succeeding in pickup games with Tar Heels veterans inside Woollen Gym, getting shooting tips from Tar Heels great Donnie Walsh and other bits of advice from Larry Brown, still the only coach to win both an NBA title and an NCAA crown.

"I played in that gym a lot," Cooper said. "Coach Smith's office was on the second floor and you could see him looking down from that window, watching you play. I felt like I was going to make it, but you didn't know. I was different from everybody else."

Smith apparently liked what he saw. Cooper made the freshman team.

"There was some anxiety about a black playing for Carolina," he said. "But you got the feeling that Smith and a lot of other people were working hard to make it happen."

The highlight of that season occurred in the freshman game -- freshmen weren't eligible for varsity competition back then -- against Clemson. Late in the contest, Cooper got an open look.

"The first shot I ever took was a high, looping jump shot from the corner," he said. "Nothing but net. The crowd went crazy."

Read one newspaper account of that game: "An historic event produced the most noise in the stands ... Willie Cooper, of Elm City, scored on his first shot...He is the first Negro to score two points for the Blue and White."

However, it went downhill from there. During a road trip to Virginia, a restaurant refused Cooper service, causing the whole team to leave. He wasn't even taken to the return game at Clemson for fear of the crowd.

"You'd hear stuff in the stands," he said of road games. "They'd call you 'Coon,' or the N-word. Even the opposing players and referees were tough on you."

But it was at the start of his sophomore season, his dream to make the varsity still real, that his worst moment arrived. Assigned to live with three white football players, he was told by the players they didn't want to room with him. He moved out. He also quit the basketball team, deciding it was all becoming too much to give his academic best.

More than 40 years later as he recalled the dorm incident, Cooper told the News and Observer: "The unwelcomeness of that was devastating to me."

Last week he added, "Lots of things were discouraging to me. I'm still trying to make sense out of it."

Yet he never felt that way about Smith.

"Dean was great," Cooper said. "He had the authority to tell the freshman coach (Ken Rosemond, who later became the head coach at Georgia), 'Don't allow him to make it.' But he didn't."

Cooper remained so loyal to the program that he went to dinner with Scott when the future All-American was being recruited.

"Even though I never played on the varsity, I like to think I made a difference," he said. "There were no incidents when I played. Everything went smoothly."

As much as it could for any black person from that time, Cooper's life went pretty smoothly from that point foward. He earned a degree in business administration. He became an officer during Vietnam. He later worked for IBM, moving to Chattanooga in 1981, where he and Helen raised three children: Brent (who played JV ball at UNC), Tonya and Cynthia.

"Dean wrote recommendation letters for both Tonya and Brent," Cooper said. "That meant a lot."

A letter from Smith 33 years ago meant more. After visiting with Cooper during UNC's visit to the Roundhouse to play the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Mocs in December of 1982, Smith wrote a letter to his former walk-on a few weeks later.

"He told me how nice it had been to see my family and me and how he was sure that if I'd come out for the team my sophomore year I would have made it and earned a scholarship," Cooper recalled.

Maybe someone will bring that up today during the Smith memorial inside the Dean Smith Center. Maybe they'll talk about All Seasons Lawn Care, the company Cooper started upon his retirement in 1993 that's still thriving. And how his love of all things Carolina Blue inspired his daughter to help the ol' alma mater win an NCAA title.

No less than Friedman told the News & Observer six years ago: "What he did is not appreciated enough."

Tonya Cooper Williams, now working on a master's degree at UNC, understandably feels the same.

"I don't think the university has ever really acknowledged what my dad did," she said. "He dealt with the brunt of it, of the initial reaction to integrating the team. Dean Smith opened the door, but my dad had the courage to walk through."

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com.