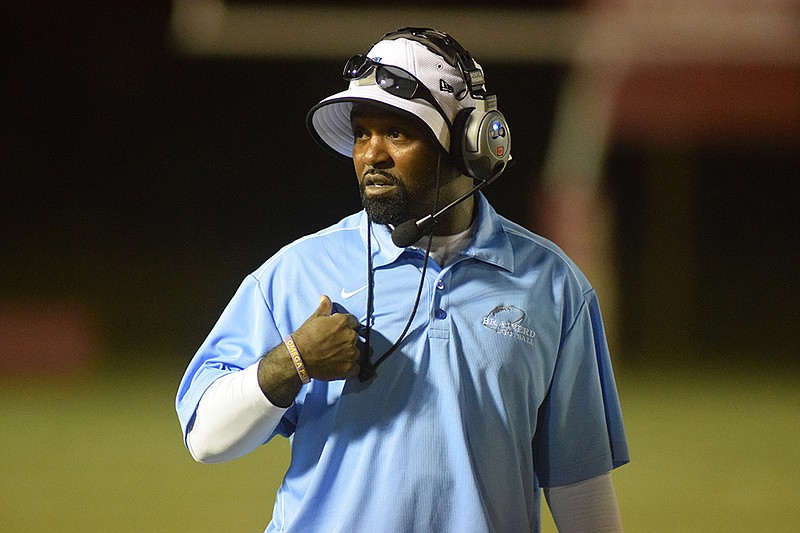

Brainerd football coach Brian Gwyn taught his Panthers a valuable lesson Friday, even if it may have been a far different one than he planned.

When Gwyn told Times Free Press sports editor Stephen Hargis on Thursday evening that his team would stage a quiet protest prior to its game at Marion County by the Panthers placing their right fists over their hearts during the playing of the national anthem, he no doubt expected them to experience the electrifying power of both freedom of speech and civil disobedience.

And those are certainly two crucial components to our democracy that so many individual protesters have been practicing of late each time they take a knee or raise a fist during the anthem to protest this country's treatment of African-Americans, especially at the hands of law enforcement.

Every American has a right to peacefully protest that which he or she believes runs counter to the laws and freedoms of our great land. In some ways, it is quite encouraging to see a new generation embrace this mindset as we have not seen it embraced since the 1960s and early 1970s.

But perhaps in his haste and hubris, Gwyn forgot another fundamental truth of adulthood: Almost all of us work for someone. And that person or persons probably has a set of rules we're to follow unless we're ready to work elsewhere.

We say this after it was swiftly disclosed Friday morning that Gwyn basically had been his own sounding board in regard to his planned protest Friday night. He hadn't consulted the Panthers players. Just as importantly, he hadn't whispered a word of this protest to his boss: Brainerd principal Uras Agee.

Thus he had no authority save his own conscience to make such a dissident decision. He'd gone rogue, become a lone wolf, flown the coop.

Worst of all, he apparently was ready to at least strongly encourage, if not force Panthers players to join him in a protest many reportedly didn't agree with.

Or as Agee adroitly assessed Friday: "In response to the statement made by Coach Gwyn, I want to say it doesn't represent myself as principal or anyone on our staff. We in no way condone any protest or actions by our students or staff that pertains to our flag or patriotism. No way in form or fashion was that going to happen."

What happens to Gwyn is less certain. Will he be reprimanded? Suspended? Fired?

Should he be?

When the desire for self-expression runs counter to the rules and values of your employer, when you attempt to run roughshod over impressionable young minds not yet sophisticated or confident enough to challenge you, what is proper punishment for your arrogance and insolence?

And of particular importance as we move forward through the athletic calendar: At what point is it fair for a high school, college or professional team to demand that its coaches and players act as one? In other words, in regard to the national anthem, shouldn't they either all stand or all sit since it's a team sport and those teams represent something much bigger than themselves?

You may well have the freedom to protest, but when that protest distracts from the team, should that team also have the freedom to tell you to stop? And since most of these teams represent public high schools and universities, which means they're funded by taxpayers, should those taxpayers have a say in the conduct of the athletes they financially support?

Beyond that, at what point does either too much freedom of self-expression by the athlete or too little freedom to be an individual within a team concept undermine the team? Is it a dress code? A curfew? Standing as one, open hand over heart for the anthem?

Once upon a time the Hall of Fame basketball player Bill Walton decided he'd had enough of legendary UCLA coach John Wooden's strict hair code. He told the Wizard of Westwood that he was going to grow his red hair long that season, that Wooden didn't have the right to demand otherwise.

Said Wooden in response: "No, I don't, Bill. I just have the right to determine who is going to play - and we're going to miss you."

Walton promptly cut his hair, apparently more concerned with helping his team win basketball games than growing his locks.

To be sure, the societal inequities driving blacks to protest are far more important and serious than long hair, as is the desperate need to relieve their anger and frustration. Almost out of the blue we are suddenly faced with a sea of complex issues that probably need a lawyer to discover the proper legal answer and a pool of lawyers and courtrooms to reach a solution if one party or the other doesn't agree with that answer.

But the practical lesson for the Brainerd football team to take from Gwyn's gross error in judgment is far more simple, and quite possibly just as important as peaceful protest and civil disobedience as they move through life.

That lesson is this: Whatever your legal rights, if you want to stay on your boss's good side, it is far wiser to ask permission than forgiveness.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com