LEARN MORETo learn more about Josh Woodrow's church plant, Bridge City Community, visit bridgecitycommunity.com.

He could hardly ignore the issue.

Standing in front of a mix of black and white faces, Josh Woodrow quickly pivoted his Sunday morning sermon to the racial unrest in Ferguson, Mo.

It should come as no surprise that Woodrow, a white man, would dive head first into issues of institutionalized racism and systematic segregation. After all, he's built his church, Bridge City Community, in Alton Park, a mostly black neighborhood known for high crime, subsidized housing and poor-performing schools. From the beginning, the idea of racial reconciliation has been a core tenet of the church.

And nowhere have the nation's racial tensions been more pressing than in Ferguson, where protesters and military-style police have filled the streets in the wake of a police officer's Aug. 9 fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager.

The unrest there has prompted discussions on everything from the overmilitarization of the police to institutionalized racism and First Amendment rights. But on the sidelines, it has stoked a conversation among some American Christians about the church's role in racial reconciliation.

And Woodrow wants to be in the middle of that conversation.

Two days before, he rewrote his Sunday sermon to incorporate Ferguson. He preached on justice, how man deserves death. Adam and Eve might have committed the world's first sin, Woodrow said, but all of mankind continues to destroy God's creation.

"Every time someone like Michael Brown gets shot, that's another rip in the wholeness of this world," he said. "Racial profiling and segregation, whether it's in St. Louis or Chattanooga -- another tear in the kingdom of God."

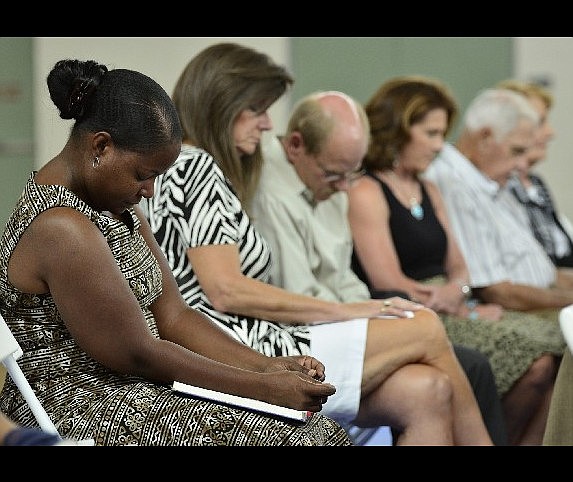

But with Jesus there is hope, he preached. Before a church member performed a Christian rap song, Woodrow led his fledgling flock in prayer.

He prayed for Brown's family, for Ferguson, Mo., and for those across the country who he said suffer racial profiling and death at the hands of those who have sworn to protect them.

"I pray that you would just give them a glimpse, a glimpse of that life you have to offer," he said, "a little foretaste of the reality that you are knitting things back together even when it doesn't look like that's true."

He prayed for comfort, peace and hope. And for courage, courage for his church to be bold here in Chattanooga.

And Woodrow is nothing if not bold.

He knows that this won't be easy, especially for a white guy from California with a handlebar mustache. He admits that he's still learning this community and doesn't have all the answers. But he says it's time that white Christians do something, to not only seek racial harmony, but to ask for forgiveness.

He went so far as to pen an apology to black Christians, admitting that the church here has tolerated and perpetuated racial injustice. He posted it in public housing sites and handed it out on the streets.

"I sincerely repent of the sins of my fathers and the pastors before me who failed to pursue reconciliation in this city," he wrote. "We have sinned against you by what we have done and by what we have left undone. We have not loved you, our neighbors, as ourselves."

Bridge City Community, a Lutheran church plant, had its first official service last Sunday at the Southside Recreation Center. But Woodrow said the church wants to be known for its actions beyond Sunday mornings. Church members walk the streets of Alton Park. They hold a Bible study with teenage boys at the rec center. And Woodrow is a constant presence at Calvin Donaldson Elementary.

"Our primary identity is the things we're doing in the community every week," he said.

For him, focusing on race comes down to a simple truth:

"The kingdom of God is anything but segregated," he said, "so it's crazy that our churches and community still are."

And American churches, especially in the South, remain largely segregated.

Churches are 10 times less diverse than the neighborhoods they sit in and are 20 times less diverse than public schools, said Michael Emerson, a sociologist who studies race and religion at Rice University.

But it wasn't always this way.

Before the Civil War, many churches were integrated, though blacks were often relegated to their own sections or balconies.

"After the Civil War, many African Americans hoped they would be accepted as equals with whites in the churches," Emerson said. "It didn't happen, and thus in the course of a few short years, black Christians exited white churches en masse, starting their own churches and denominations."

Emerson's research has found increasing polarization surrounding race, the evangelical magazine Christianity Today reported.

More evangelicals and Catholics have come to believe that "one of the most effective ways to improve race relations is to stop talking about race," the magazine said. And more evangelicals today believe "it is OK for the races to be separate, as long as they have equal opportunity."

Changing longstanding church segregation takes effort from whites and blacks alike, said Kevin Adams, pastor of Olivet Baptist Church, a predominantly black congregation on M.L. King Boulevard.

"I don't believe there's a black church or a white church," he said. "I don't believe it's a matter of race, but grace. And I think that after Jesus died for us over 2,000 years ago, for us to still be having that discussion about a black and a white church is really disheartening."

The Bible said Jesus' followers would be known by their love for one another, Adams said. So if Christians would focus more on love, issues like discrimination and racism would take care of themselves.

"If we major in the great commandment, the golden rule, you can't help but for whites and blacks to come together," he said. "We can't help but to be unified."

He said Olivet, an independent Baptist church, has built a diverse congregation of whites, blacks and Hispanics. To truly be inclusive, he says, a church must be diverse in both leadership and worship. Adams said he supports Woodrow's idea to offer an apology, because sometimes the elephant in the room just needs to be addressed.

"But sometimes that apology needs to be done on both sides," he said.

"I'm not against anybody who's out there trying to reach this community. But I think it has to be greater than blacks going after whites or whites going after blacks. There needs to be a cause, going after souls, addressing issues. There's a whole lot of hurting people out there, whether they're white or black."

Brian Merritt, a local Presbyterian minister, traveled to Missouri last week to support the Ferguson community. He said Christians have a responsibility to follow Jesus' example of standing with the oppressed.

"That's what a lot of us feel right now in this situation," he said. "And it really heightens my focus on the inequalities we have at home in Chattanooga."

Merritt runs Mercy Junction, a ministry housed in the Westside's Renaissance Presbyterian Church. He said simply preaching about equality from the pulpit isn't good enough. Churches like to talk about forgiveness and repentance, Merritt said, but in reality they are tough things. And they aren't achieved overnight.

"They take a lifelong commitment of walking with people," he said.

Merritt said many churches venture in and out of poor, black neighborhoods, what he calls a kind of "evangelical tourism." Humility is key to bridging the divide, he said.

Trying to act like Jesus is one thing, but acting like a savior is another.

"Maybe my salvation is dependent on being with people in the Westside," he said. "Maybe they need to show me as a Caucasian minister of Jesus Christ something that will save me. Not that I need to save them."

Contact staff writer Kevin Hardy at khardy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6259.