NASHVILLE - There is wide disagreement in Tennessee on whether the state is violating recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions banning mandatory life-without-parole sentences for offenders under 18. That's because judges and juries have a choice in sentencing, but that choice is between life in prison or life with the possibility of parole after serving 51 years - which one leading advocate calls cruel.

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed mandatory life without parole for juveniles convicted of murder. Last year, the court said the ruling applied to the more than 2,000 inmates already serving such sentences nationwide, and that all but the rare irredeemable juvenile offender should have a chance at parole. The rulings say juveniles are different because of poor judgment based on their age, their susceptibility to negative influences and their greater capacity for change.

In other states, dozens of offenders have been resentenced and some paroled, but Tennessee so far is not offering resentencing to its 13 juvenile life-without-parole inmates. The youngest at the time of his crime was Jason Bryant, who was 14 when he and five others kidnapped the Lillelid family from a rest stop in eastern Tennessee and killed the mother, father and their 6-year-old daughter and wounded the couple's 2-year-old son. The 1997 crime garnered international attention because prosecutors said satanic rituals were involved.

Bryant has been cast as either a victim who was blamed by older kids who perpetrated the crime but wanted him to take the rap, or a cold-blooded killer who was at least one of the shooters executing the family as they begged for their lives.

Greene County District Attorney Dan Armstrong, whose office prosecuted Bryant, noted that the Supreme Court's rulings said there are some cases where juveniles should serve life - when the crime reflects "permanent incorrigibility." Armstrong said that "if there's any case in the world that meets that exception, it's the Lillelid case. That family was basically lined up in a ditch, begging for their lives and shot. And then that wasn't enough: They ran the van over them as they left."

Bryant has filed a petition challenging his life-without-parole sentence.

Another roughly 100 former teen offenders in the state must serve the minimum 51 years before parole eligibility, records from the Tennessee Department of Correction show. The Supreme Court has yet to rule on whether lengthy alternative sentences to life without parole are constitutional, Marsha Levick of the national Juvenile Law Center said, but she believes those cases eventually will be taken up.

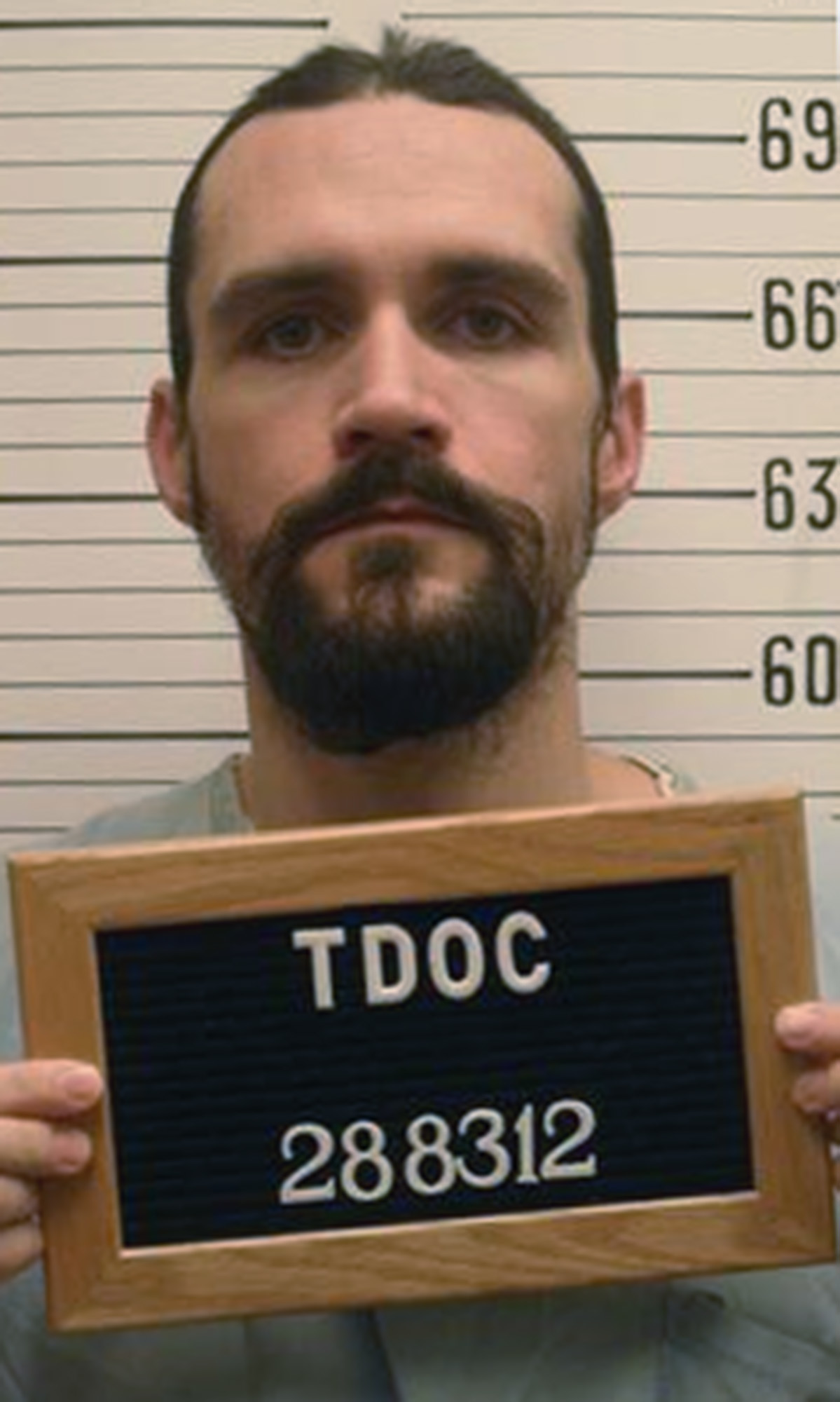

This undated photo provided by the Tennessee Department of Correction in 2017 shows Jason Bryant. Bryant is serving a life sentence for a crime he committed when he was 14 years old. He and and five other juveniles from Kentucky killed Vidar and Delfina Lillelid and their 6-year-old daughter, Tabitha, and gravely wounded the couple's 2-year-old son after kidnapping the family at a rest area in eastern Tennessee in 1997. (Tennessee Department of Correction via AP)

This undated photo provided by the Tennessee Department of Correction in 2017 shows Jason Bryant. Bryant is serving a life sentence for a crime he committed when he was 14 years old. He and and five other juveniles from Kentucky killed Vidar and Delfina Lillelid and their 6-year-old daughter, Tabitha, and gravely wounded the couple's 2-year-old son after kidnapping the family at a rest area in eastern Tennessee in 1997. (Tennessee Department of Correction via AP) "I am not aware of any other state in the country that has those two options and only those two options," said Levick, the advocate who called Tennessee's situation cruel. "The 51-to-life is the most extreme so-called alternative to the law that I've heard."

Officials with Nashville's Juvenile Court have been pushing to reduce the 51-year provision, as well as other lengthy sentences for those who committed crimes while under the age of 18. "The court is not advocating that all these kids get out," court administrator Kathryn Sinback said, but she added that such inmates should at least have a meaningful chance, after a reasonable amount of time, to show they've been rehabilitated.

The Juvenile Court backed a bill this past legislative session that would have allowed young offenders to be eligible for parole after 20 years for crimes that resulted in someone's death. That bill was amended to 30 years, but many who are pushing for changes say that's too long.

The proposal also would have allowed juveniles to be eligible for a shot at parole after serving 15 years when their crimes didn't result in the death of someone. The bill was pulled but will be up again next year. A new bipartisan state task force on juvenile justice reform met for the first time in June, and the body could recommend changes to sentencing guidelines for young offenders.

There is at least one case in Tennessee courts that challenges the 51-year sentence. The case involves Jacob Lee Davis, who was an 18-year-old senior in high school when he shot and killed a man his then-girlfriend was dating.

Even though Davis was not a juvenile offender at the time, his court battle has implications for all those serving or facing life sentences with the possibility of parole in the state, regardless of their age at the time of offense, wrote Will Howell, an attorney in the case, in an email.

Davis has argued that he should be eligible for parole after serving 25 years and maintains that the 51-year provision means he has essentially been condemned to serve the rest of his life behind bars.