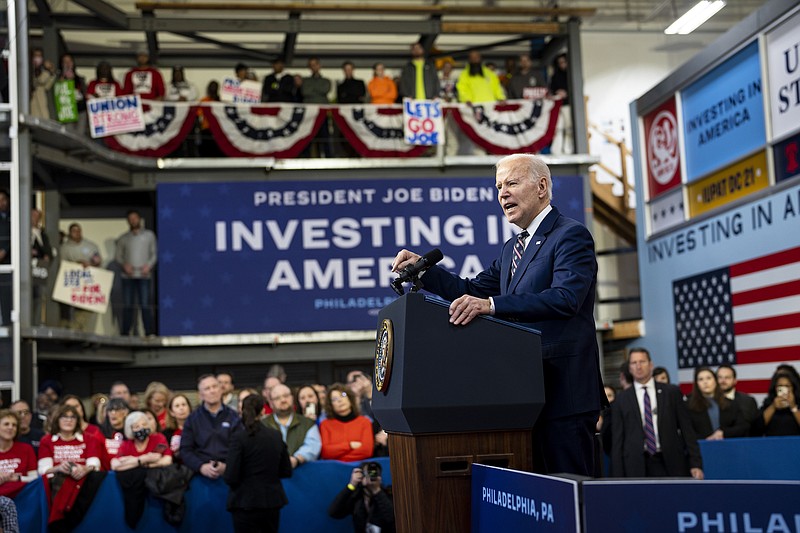

President Joe Biden's latest budget calls for maintaining and even expanding the social safety net, although it seeks to limit Medicare spending through tougher bargaining over drug prices. It nonetheless claims to reduce budget deficits, mainly by raising taxes on corporations and Americans with incomes over $400,000 a year.

For now, it's a sensible approach, especially given the political realities. But in the long run we'll need more.

First, we don't currently face a debt crisis, nor are we likely to face such a crisis any time soon. It's always important to remember that while our debt is huge in absolute terms, so is everything about the U.S. economy, so citing big numbers without context isn't helpful.

If we do look at debt as a percentage of GDP, it's indeed high, but not outside ranges that other countries have managed without crisis. Britain spent large parts of both the 19th and 20th centuries with debt well above current U.S. levels, but without experiencing a severe debt crisis.

Still, even those of us who reject deficit scare talk generally think that at some point we'll have to stabilize the ratio of debt to GDP. What would stabilizing that ratio involve?

It would not mean balancing the budget. Because GDP grows over time, a stable debt ratio can be achieved even with growing debt, as long as the growth is no faster than that of GDP. Right now, we have debt that's roughly 100% of GDP; a reasonable long-term projection for long-term GDP growth is 4% a year -- half real growth, half inflation -- so we could hold the line while adding debt -- that is, running deficits -- of 4% of GDP each year.

Actual deficits are, however, somewhat bigger than that; the Congressional Budget Office expects a deficit of 5.3% of GDP this fiscal year. That's not a huge gap, but we're on a trajectory that will, absent policy changes, make the debt-to-GDP ratio worse. The reason is the combination of an aging population and the likelihood -- again, in the absence of policy changes -- of rising health care costs.

The CBO's long-term budget outlook projects that the fiscal gap -- the difference between the actual budget deficit and the deficit consistent with a stable debt ratio -- will eventually rise by more than 5% of GDP. Since we already have a gap of 1-2 points, we're looking at an eventual gap of, say, 6-7 points. How can that gap be closed?

Controlling health care costs could be a large part of the answer. It's always important to realize that American health care is wildly more expensive than health care in other advanced countries, without achieving meaningfully better results.

So if we're willing to take real action on health costs, we should be able to avoid most or all of that additional cost growth. Yes, it will be hard -- but not as hard, or as cruel, as simply kicking people off Medicare and Medicaid, which seems to be the Republican solution.

But even if we can control health costs, adding the effects of an aging population to the fiscal gap we already have will still mean a fairly large fiscal gap several decades from now -- say, 4% or 5% of GDP. If we want to preserve benefits, we'll have to close that gap with additional revenue.

Can all of that revenue come from taxes on very high incomes? Unfortunately, I don't think so.

I've been playing around a bit with IRS tax data; I'm sure that actual tax economists can do a more sophisticated analysis, but here's a quick and dirty approach. Let's approximate a strategy of taxing the rich with one of raising taxes on ordinary income that's already being taxed at a 35% or 37% rate -- in other words, the income of the highest earners -- and capital gains taxed at 20%, the type of investment income also enjoyed by wealthier Americans.

The total remaining untaxed income of the rich, if I'm doing the sums right, is about 6.5% of GDP. But the amount of money we could raise with higher taxes on this income is surely considerably less than this total, even in the unlikely event that we tried to tax all of it. For one thing, this is the income net of federal taxes; some of that income is already being paid in state and local taxes.

Probably more important, very high marginal tax rates create problematic incentives. Conservatives emphasize how taxes reduce the incentive to work and create wealth; this effect is surely overrated, but it does exist. More important, high tax rates encourage extraordinary efforts to avoid taxes (which is legal) or evade them (which isn't). Estimates of the revenue-maximizing top tax rate tend to be in the range of 70-80%, well above the federal maximum of 37%, but bear in mind that many high earners also face state and local taxes that raise their effective marginal rate to something like 50%.

So the amount of additional revenue we can raise from taxing the rich, while substantial, is considerably less than their remaining untaxed income. It may be as much as 2% of GDP, but that won't be enough to close the long-run fiscal gap.

My bottom line is that, yes, we can preserve Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security without benefit cuts through a combination of cost control and tax increases, but that we'll eventually have to raise taxes, at least somewhat, on people making less than $400,000. The operative word, however, is "eventually."

Put it this way: Broader tax hikes can wait until U.S. politics become less poisonous. And if they don't become less poisonous, fiscal gaps are going to be the least of our problems.

The New York Times