WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. - In October 1918, the last great pandemic to strike America forced the cancellation of public meetings and schools.

People were urged to kiss only through handkerchiefs. Pharmacies preached patience as they struggled to keep up with orders for medicine. A newspaper touted castor oil as a preventative medicine.

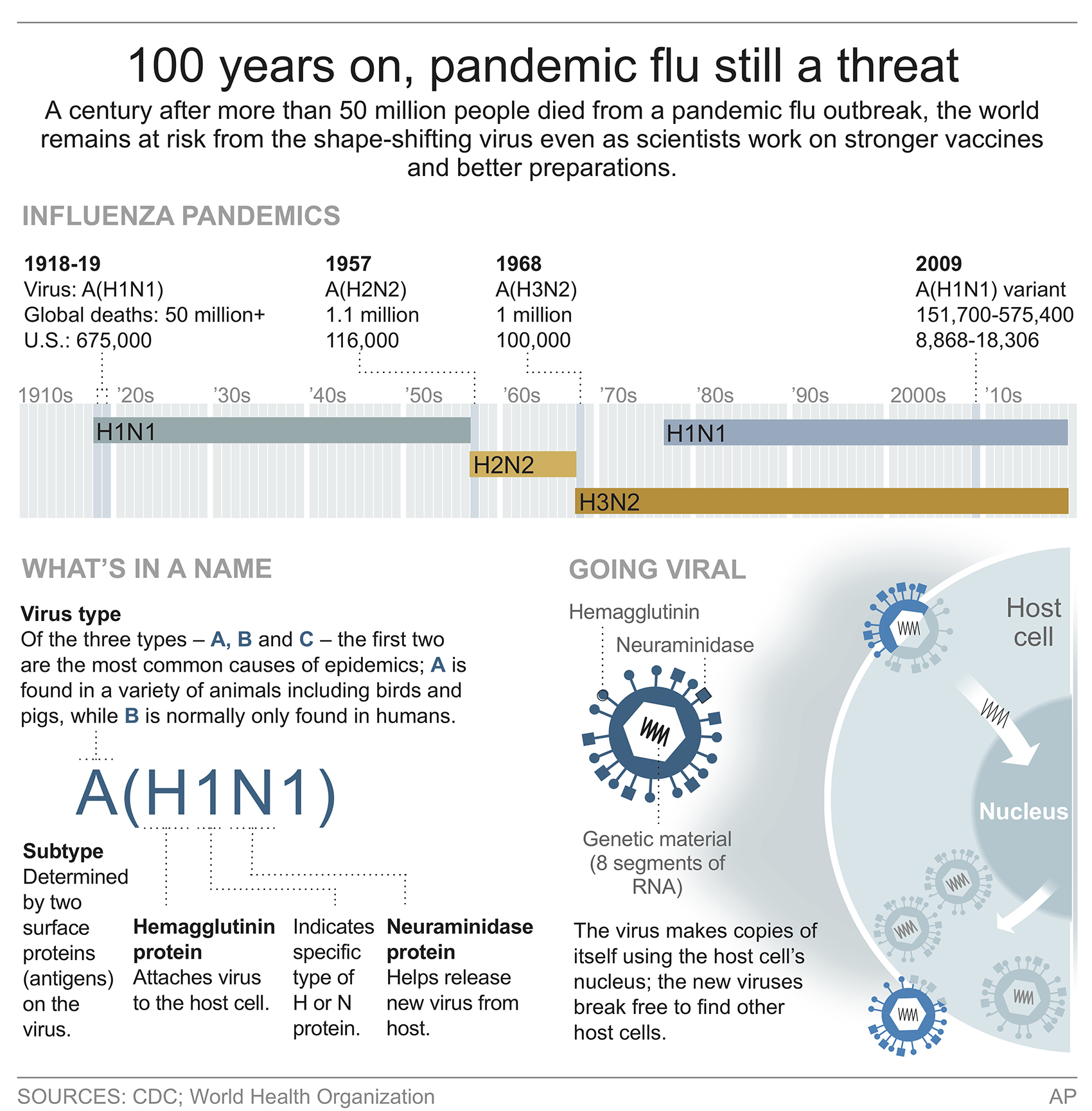

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 1918 pandemic, caused by a virus we all know too well: influenza.

The Spanish flu conducted itself like few of its predecessors. It didn't strike down infants or the elderly so much. Its chief targets were healthy young adults. These able-bodied people succumbed when their immune system went haywire trying to fight the virus.

"People hadn't seen the flu in a generation and that meant there was a whole bunch of people who hadn't been exposed to it and therefore didn't have particular immunity," said Mike Farzan, a professor in the department of immunology and microbiology at Scripps Research Institute in Jupiter, Florida.

In the end, exactly how many people died from this strain of H1N1 virus is unknown, but it may have been as high as 50 million worldwide. World War I, by comparison, killed about 40 million. U.S. life expectancy dropped by about 12 years after more than 500,000 people died in this country.

It started in spring of that year, then the most deadly second wave of the mutated virus appeared in the autumn of 1918, at the tail end of the war. A third, less virulent wave hit in 1919.

"It was a blink of an eye," said Laura Spinney, whose book "Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World" takes a global look at the pandemic. "People didn't know what hit them."

And as a result, the last great pandemic is often not considered as historically devastating as other 20th century events, but Spinney said its toll is immeasurable.

'Panic everywhere'

"There was sort of panic everywhere," she said. "It was completely catastrophic. It ripped the hearts out of families. Pillars of communities who had survived the war were struck down by the flu. It was a social and economic disaster."

Many families were forever reshaped as spouses died and children were orphaned, Spinney said. "There was this great big rupture," she said.

A century later, the current strains of the flu are less deadly, but they are far from nonlethal. Florida Department of Health estimates 3,000 people have died from pneumonia or flu statewide this season. A West Palm Beach 12-year-old died Jan. 23 from complications of the flu, his family says.

But the flu panic that engulfed the state and the nation in the fall of 1918 has never been seen since in the age of vaccinations.

The first word of the epidemic came from the war theater. The flu got its name because only Spain, which was neutral, reported the outbreak. The origins of the virus remain up for debate - suspects range from the trenches of France to a respiratory outbreak in China to Army barracks in Kansas.

One theory is that Chinese laborers transported the flu when they went to work on the front lines of the war.

"There are a lot of questions as to what caused the pandemic. ... There are a lot of controversies," said Farzan, the Scripps flu guru.

World War I

The flu found a place in which to thrive in the 1918 landscape dominated by World War I. Soldiers coming home from the front lines or heading there created a superhighway for the virus to travel. Livestock, birds and pigs, which can carry the virus, were everywhere.

"The virus probably found a very good environment due to World War I to replicate in the young," Farzan said.

The Spanish flu infected every nook and cranny of the world; even isolated populations in Alaska and Samoa were hit badly.

The Palm Beach Post reported on Oct. 9, 1918, of an ordinance passed by the city of West Palm Beach to close all public meetings, schools, theaters, churches and gatherings of all kinds until the danger had passed.

"It was stipulated in the ordinance that there shall be no loitering in billiard halls, that barbershops shall be conducted in a strictly sanitary manner and that soda fountains shall serve drinks only in paper containers," according to the front-page story.

The ordinance was to be strictly enforced, with violations carrying a $100 fine or 30 days in jail. In 1918, $100 carried the purchasing power of $1,762 today.

Hours of stores were curtailed - except pharmacies, which struggled to meet demands.

Florida - unlike New England, which reported 55 deaths in one 24-hour stretch - was largely spared the thousands of deaths, but families were concerned about their children housed in close quarters, whether at universities or in barracks. The Post reported to parents that the flu had largely spared Florida State University.

At the time the Spanish flu struck, Florida had fewer than 1 million residents - 4 percent of its population today. Still, the state reported thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths from the Spanish flu, according to findings from 2006, when each state held pandemic planning summits.

"City ordinances mandated quarantines and the wearing of face masks in public. Public gatherings were banned, and schools and churches were closed," Florida's report stated.

Mr. Olson from Ocala

Still, not everybody heeded warnings, the report stated.

An Ocala man - identified only as Mr. Olson - traveled to Jacksonville for a carpentry job despite the citywide quarantine and requirement of gauze face masks. When he caught the flu, the worker slipped past guards, caught a train back home and infected his family and others.

But for the most part, much of the bad news on the flu for Palm Beach County residents came from out of state.

Ned Pendleton, described only as a young man, caught the virus at Camp Dix, N.J., after three weeks of military training and died. Walter J. Kline, 27, also developed pneumonia from the flu and died at Wright Brothers Aviation Training Camp in Dayton, Ohio. He had enlisted.

Word came that well-known winter residents and workers had passed in the Northeast from the flu.

The Prohibition movement, in full swing, took advantage of the outbreak as health boards warned people to abstain from all alcoholic beverages as a preventative measure.

And when it came to preventative measures, tonic oil seemed to be the cure du jour. There were no antibiotics in 1918.

On Nov. 4, 1918, Palm Beach Post columnist Joe Earman reported that castor oil was the reason none of the paper's 26 employees caught the Spanish flu. Earman had a penchant for emphasizing parts of his column by writing in capital letters.

"Castor oil is MY MEDICINE - REMEDY FOR EVERYTHING," he writes. "Buy it by the gallon, and the gallon bottle sits on my desk in full view."

Earman also recounts the fear the flu caused in 1918 when Judge Walter "Old Thorn" Thorndyke caught the bug and how a woman identified as community leader Miss Berthe Elliot "rushed in my office next door with a look of terror in her face. She was simply 'scared to death' and stated that Mr. Thorndyke was gasping for breath."

Elliot's concern was for naught, though. It turned out Thorndyke merely had food poisoning from eating canned shrimp.