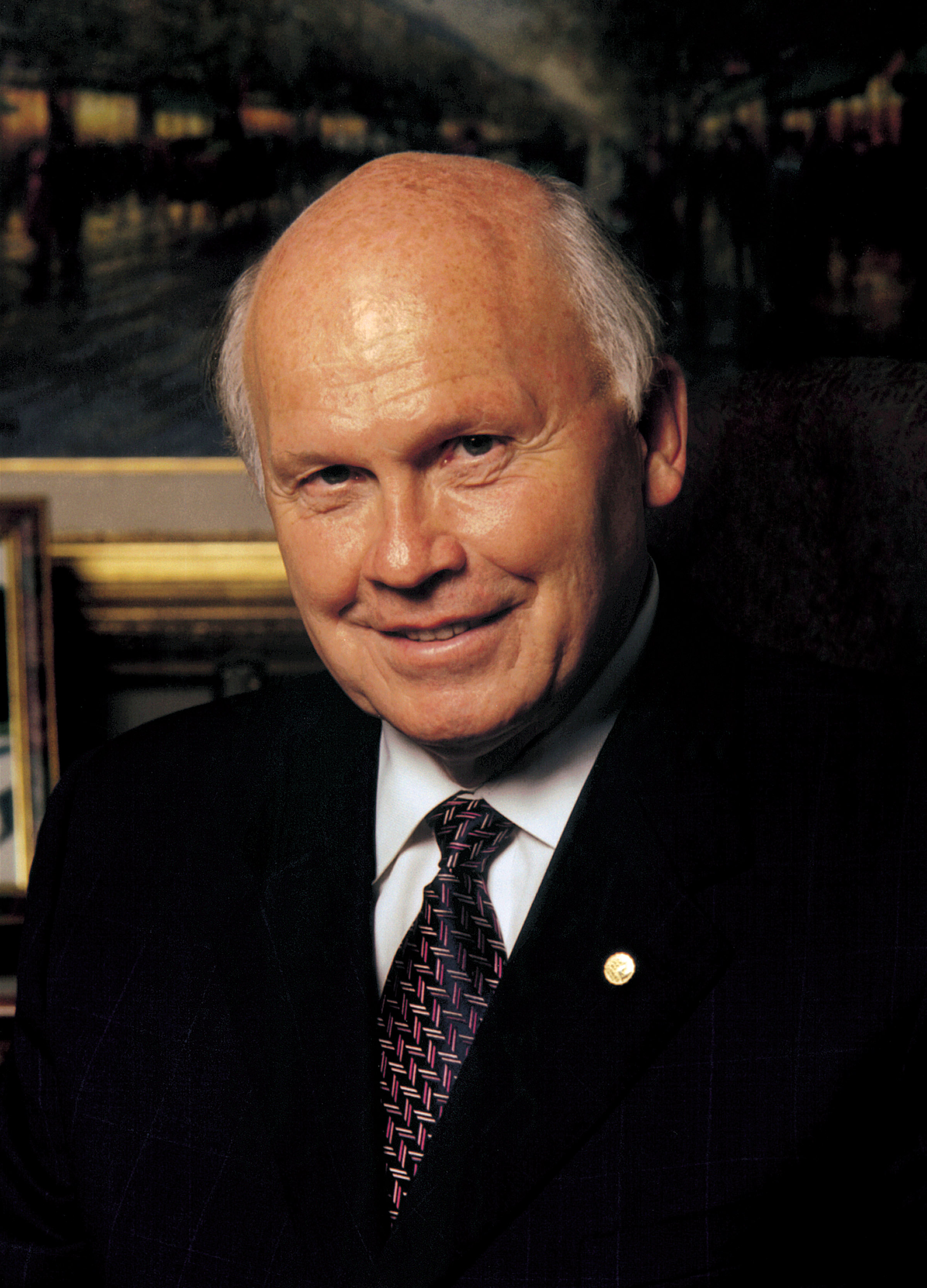

On a cold afternoon in mid-winter, Forrest Preston stands on the edge of a crowd gathered in the dining hall at Life Care Center of Cleveland, there to honor the 45th anniversary of the opening of Preston's first facility.

Preston, 82, moves to the center of the floor to say a few words. He's fighting off a migraine headache that began, he says, during the walk in from the car. He eats half a Snickers bar to curb the discomfort.

Preston looks around the room, at the local elected officials, at LifeCare higher-ups and at a group of nurses dressed all in traditional white scrubs and hat. He chokes up as he addresses them. The nurses are so important, he says.

He recalls in 1970 moving into this first facility, then called Garden Terrace Convalescent Center, and having his kids carry furniture off the trucks and assemble it in the dining hall. He had friends come in and do carpentry and painting.

The first night of operation, Preston says he stood in this dining hall and made a bold prediction.

"I said these lights will never go off again until the second coming," he says.

Today, Life Care Centers of America is the largest privately-owned long-term care facility chain in the United States with facilities across 28 states. It's the third-largest long-term care chain in the nation.

Forbes magazine estimates Preston's ownership of Life Care gives him a personal wealth of $2.1 billion enough to make him the richest man in Southeast Tennessee and land him on Forbes list of the 400 richest people in America.

It's said that Preston hates the Forbes listing. He hates the attention, hates the risk he feels it places on his family. Preston lives in sprawling estate in the same north Cleveland neighborhood where Check Into Cash founder and multimillionaire Allan Jones built his hilltop estate.

For all his wealth and business success, Preston doesn't covet publicity. When asked, he tries to play down his own role in the company he built (he remains the sole shareholder). He says it's the people, the staff of the facilities who deserve recognition, not him."I could introduce you to 50 people," he says. "And 20 of them could run the company."

But most in his field view him as a larger-than-life titan of the industry. He's considered among those who have single-handedly changed the long-term care industry. And he's still changing it, albeit quietly.

Over nearly a half century in the business, Preston has had to cope with changing Medicare rules, insurance regulations, building codes and technology advances. Preston and his company continue to face a 7-year-old government probe and federal lawsuit claiming the company committed Medicare fraud by ordering too many procedures and charging too many expenses to Medicare. Life Care denies the charges, which, if proven, could cost Life Care millions of dollars and hurt its reputation.

Preston and his colleagues insist they take pride in their business, which Preston says has been guided by the Christian principles he learned from his father, a Seventh Day Adventist pastor.

Company leaders say Life Care's growth can be traced to a corporate culture built around connecting with people, and Preston's uncanny ability to sell.

Getting started: From vacuum cleaners to hospital publications

A Massachusetts native, Forrest Preston came to Cleveland in the late 1950s to join his brother, Winton, who had started a printing business.

The son of a Seventh Day Adventist pastor, Winton attended Southern Adventist University in Collegedale. He stayed in the area after school and eventually started his company in Cleveland.

Forrest, meanwhile, wound up attending Walla Walla College, a little town in Washington state near the Oregon border. Preston's father was assigned to pastor a congregation in Spokane, Wash., a town on the Idaho line about a three-hour drive from Canada.

Forrest was studying to be a physician; it's what his family wanted. But inorganic chemistry got the best of the young Forrest, and he decided the life of a physician was not in his future.

Something else important happened while Preston was in Washington. To help make ends meet during school, he took a part-time job selling Electrolux vacuum cleaners. And he was very good at it.

Preston wound up enrolling at a school in California and studying to be an X-ray lab technician. He went to work for a hospital in California, and noticed that many hospitals didn't have public relations or marketing teams.

Preston believed that he could help fill that gap, and knew that he had a good place to start, with his brother running a printing business back in Cleveland. So he moved to Tennessee and together with Winton, started Hospital Publications, Inc., which acted as a third-party marketing firm for hospital clients. Preston formed a traveling sales team and led them around the country selling Hospital Publications' services. He was a successful businessman before his first care facility even opened its doors.

Heading into the 1970s, Preston was visiting hospitals all over the country, many of which also operated long-term care facilities.

"He was disturbed by some of the conditions he saw," says Hunter. "He thought it should be better than that."

Building a start in Cleveland

He found a builder, Farrell Jones, willing to go in with him and open a long-term care facility in Cleveland. The idea was to build a facility nicer than any other of the day, to provide better care than anyone else.

But there was no seed money. Preston called on a man he had made back in the Pacific Northwest, Carl Campbell, a long-term care facility contractor. Preston and Jones flew to Washington and showed up at Campbell's office unannounced at 8 a.m. one day. Campbell was headed out of town for business but invited the two entrepreneurs-to-be to fly with him and talk business.

They reached an agreement to form a partnership of three, and to build a facility in Cleveland, Garden Terrace Convalescent Center.

"Under an umbrella stand in Idaho they secured financing for the first [to-be Life Care] nursing home in Cleveland," Hunter explains.

Between 1970 and 1976, the painters built six centers under the name Development Enterprises. Among those first facilities are Life Care centers still in operation in Cleveland and East Ridge. Preston was the first facility administrator in the company's history, but he soon found it overwhelming trying to manage six centers. In 1976, he formed a management company for the centers called Life Care.

When asked about the business plan that saw Life Care balloon into the giant it is today, Preston says it's always been about building relationships.

"The word just spreads," he says. "It grew. It's amazing you can go and just meet someone on an airplane and you have an idea."

But Preston, beneath the titles and preconceived ideas of a small-town billionaire, is actually remarkably personable according to those who know him.

"He is a people person," says Beecher Hunter, president of Life Care and an associate of Preston's for four decades.

Hunter says on road trips to facilities around the country, Preston enjoys showing up and talking with facility staffers, residents and families of residents.

As CEO of a company with 42,000 employees, Preston particularly enjoys talking with his staff. He often spends time conversing with kitchen staff. And laundry staff. And boiler room staff.

"It sort of counters what most people think of a large corporation," Hunter says.

Hunter says he once visited a facility with Preston, and the Life Care founder and sole owner struck up a conversation with a male resident.

How is the food? Preston is said to have asked.

The man gave a ho-hum answer. Then said he'd like to have "a good old hamburger," says Hunter.

So Forrest Preston had someone bring the man a hamburger.

Hunter says Preston is always looking for knowledge and believes he can learn something from anybody.

"He maximizes the opportunity to converse with people, sometimes at great lengths," Hunter says.

Life Care "graduates" branch out

Last month, a new Morning Pointe assisted living center opened off Shallowford Road in Chattanooga. Morning Pointe is operated by Chattanooga-based Independent Healthcare Properties. The company operates 24 facilities in the U.S. and plans to expand to 30 facilities within a year-and-a-half.

Greg Vital, president and CEO of Independent Healthcare Properties, is another local entrepreneur whose leaving his own mark on long-term care. Successful in his own right, Vital is also a former Life Care executive and colleague of Preston's.

Vital says Preston is a savvy businessman, which is evident in Life Care's growth, but that he's also a mentor of young executives and visionaries. Preston sees and understands that same drive in others.

"He knows people just like himself want to go out and do something," says Vital.

Vital left Life Care around 20 years ago and says that when folks leave the company, Preston "leaves you alone for a while," to find your own way. But Preston later would call when he would be in town and would invite Vital to grab lunch at Cracker Barrel or coffee somewhere.

"Of several people in my life who are mentors, I consider Forrest Preston one of those," he says.

Vital echoes what many close to Preston say about the driving force behind the man who built Life Care from the ground up. It's a commitment to do better, be better than before. It's a drive to offer the best service.

"Mr. Preston's contribution to the industry has been continuing to raise the bar, whether it be program activities or physical plants and structures," Vital says. "He's a visionary."

Vital says that in the 10 years he worked for Preston, "I earned five Ph.Ds" drawing on the knowledge and experience at hand. He says Preston is to the long-term care industry what Sam Walton was to retail, calling his former boss "a legend in long-term care."

Preston is now facing perhaps the biggest challenge to Life Care.

Federal prosecutors allege Life Care Centers has bilked the federal government of hundreds of millions of dollars through a systematic Medicare fraud scheme since 2006. A federal investigation of the company began in 2008 when Life Care employees in Florida and Tennessee filed whistle blower lawsuits claiming the company told employees to maximize unnecessary therapies for patients to get more Medicare reimbursements. Life Care is paid nearly $1 billion a year in Medicare payments.

The whisteblower lawsuit was combined with a government lawsuit against Life Care in 2012 and the case is still going through evidence discovery. Prosecutors claim the Medicare fraud began at the highest levels of the company, including claims that Preston forbade his compliance department from conducting unannounced inspections at facilities. Critics of Life Care say the company has made staff sacrifices in order to keep profits up.

But Preston says his intentions for Life Care have only been to create a positive culture, one that is rooted in the Golden Rule and places confidence in the company's workers and managers. He says he goes after high-caliber individuals with clean pasts.

During a company reception, Preston points to one of his nurses who grew up in Crossville and helps staff one of the Life Care centers. "We could go to Crossville and not find one person who could say a bad thing about her," Preston says.

Going to work everyday

Preston, 82 now, still works every day. He also helps care for his wife, who suffered a stroke a few years ago.

Preston says he still enjoys working. He says he is still able to break away and spend time with family. He doesn't seem to be eyeing retirement, at least anytime soon.

If there's a succession plan for Life Care, it's a closely-held secret known only by Preston, who remains sole owner of the company's shares. He says banks and institutions have faith in the current system, "and that's the main thing" to keeping that way for so long. Preston has three sons and one daughter. None of the children work for Life Care, but some grandchildren do.

"My wife says they'll probably find me in a corner someday, run out of gas," Preston says.

Preston says going forward, Life Care is going to focus on its skilled care, post-acute care and assisted-living facilities. It recently jettisoned its home care wing to a Louisiana home health company.

The baby boomer generation is creating a wave of new long-term care residents in the country, with 10,000 Americans turning 65 a day, a trend expected to extend over the next 20 years.

Preston knows that after all these years, it's still a good time to be in the business.

This article appears in the April issue of Edge magazine, which may be viewed online at www.meetsforbusiness.com