CLEVELAND, Tenn. - Here at the heavily traveled intersection of Eighth and Ocoee streets, a pair of skinny, stone monuments compete for the attention of passersby.

"Don't forget Cleveland's lost sons," the taller one reads - those "known and unknown" boys who died fighting the Union during the Civil War.

But there's another tale represented here: a tragic story of three prominent young Cleveland businessmen who were killed July 2, 1889, 126 years ago, in a fiery train wreck near the tiny commonwealth town of Thaxton, Va.

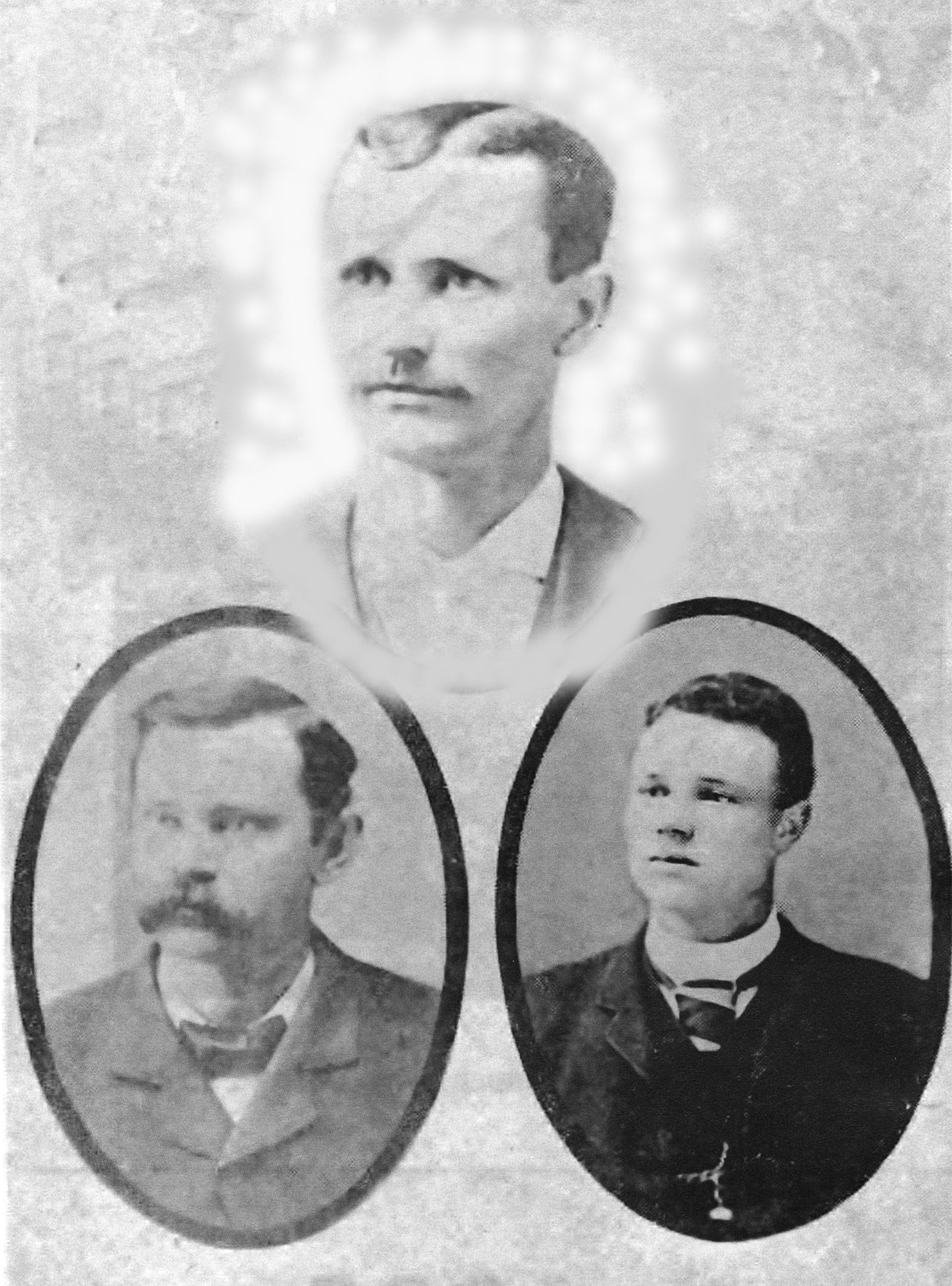

In the year following that train wreck, a monument to the three victims - John Hardwick, Will Marshall and Will Steed - was erected in Cleveland.

Meanwhile, 360 miles away in Thaxton, no monument or marker was ever placed, leaving the site of one of Virginia's worst train crashes to fade into memory.

And it might have remained so, if not for a Lee University coed colliding with Cleveland's Thaxton monument last spring, which led local millionaire and businessman Allan Jones to take an interest in the tragedy at Thaxton.

Jones had recently acquired Hardwick Clothes - the Cleveland suit maker once owned by Thaxton victim John Hardwick's family - in federal bankruptcy court. He was interviewing job candidates when the phone rang.

It's one of the monuments at Eighth and Ocoee, the voice on the other line said. It's been hit, toppled.

"And I ran out the door," remembers Jones. "Our monument that had been standing there for 125 years had been knocked over."

He arrived on the scene and found that it wasn't the Confederate soldiers monument, but the train wreck monument lying on the ground cracked and broken.

A history buff and lover of all things Cleveland, Jones despaired to see a piece of his childhood disappear.

"All my life I remember riding my bicycle and pulling over to look at that monument," he says.

He questioned city leaders about what would happen to it. They said they didn't know if money was available to have it fixed.

So Jones reached into his own pocket to repair it, and in the process, he began researching the fatal train crash involving Hardwick, Marshall and Steed.

He found ample information and decided to make a pilgrimage to Thaxton, now a small, unincorporated community in Bedford County, Va. He was shocked to find no marker to the 18 (or more) victims of the 1889 wreck of Norfolk & Western Passenger Train Number Two.

"I couldn't believe Cleveland would put up a monument and the little town where this happened didn't put up anything," he said.

Again, Jones prodded officials: Why was there no monument? How difficult would it be to change that? What if a private, third-party stepped in to bankroll such a project?

It took nearly 12 months and a bit of lobbying to grease the wheels, but earlier this year, Thaxton's first historic marker commemorating the deadly crash was unveiled. Jones flew up for the event and took along a group of Cleveland residents with ties or interests in the crash.

Among them was local historian Debbie Riggs, author of "The Day Cleveland Cried," a book dedicated to exploring the background, lead-up and eventual events of July 2, 1889.

Riggs talks about how Hardwick, Marshall and Steed bore three of the most prominent last names in the city at the time of the crash.Hardwick's family started and owned Hardwick Stove and Hardwick Clothes. Marshall was Cleveland's city planner, and his family owned a lumber mill. Steed and his brother ran a drugstore in the courthouse square.

There was much fanfare in Cleveland when the three young men left for Paris to see the Exposition Universalle (World's Fair) and the premiere of the Eiffel Tower.

An estimated 2,000 townspeople gathered on July 1, 1889, to see them off. But overnight and into the morning, heavy rains washed away a steep dirt bank under the rail line in Virginia, and the land gave way.

The train carrying Cleveland's pride went headfirst into the ground, and the locomotive exploded, catching the first-class car carrying Hardwick, Marshall and Steed on fire.

Only Steed could be identified later.

Riggs knows the story inside and out and says that standing in Thaxton this spring, looking at the actual spot where Cleveland's heart broke 126 years ago, was surreal.

"I can't describe it," she said. "You're thinking back to all that flooding. Then you're picturing C.L. Hardwick walking up and down those tracks looking for his son."

"The newspapers said everyone wore sad faces for days," says Riggs. Fourth of July festivities were cancelled.

The following year, Cleveland residents and families of the three deceased sons raised a stone monument at the intersection of present-day Eighth and Ocoee streets.

The monument was taken down for a while as the families fought over its location, but it was ultimately put back in its original place, where it sits today.

And it was later overshadowed by the taller Confederate soldier monument that now stands beside it.

Riggs said for a time, before all of this, the story of Thaxton and its Cleveland victims was forgotten.

"So many people see the monument," she said. "There's the Confederate monument, and there's - what we call the boys' monument - sitting there together. So many people see it, but they never really see it."

Even so, the monument is there, and will be henceforth.

And although it took 126 years, the people of Thaxton - thanks in part to the people of Cleveland - can finally say the same thing.

Contact staff writer Alex Green at agreen@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6480.