When Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy last month, the fast fashion chain described its history in documents that read, at times, like a pitch for a memoir or a Netflix special.

Photos of the company's husband and wife founders, Do Won and Jin Sook Chang, and their two daughters appeared under headings like "Forever Striving: A Story of Grit, Determination, and Passion." The filing emphasized the improbable success of the Changs, who immigrated to the United States from South Korea in 1981 and built a multibillion-dollar business from scratch.

There were references to the daughters' undergraduate degrees from "Ivy League universities" - both are top executives at the company - and summer breaks spent at Forever 21 stores. A definition of the American dream, as explained by Investopedia.com, even appeared on one page.

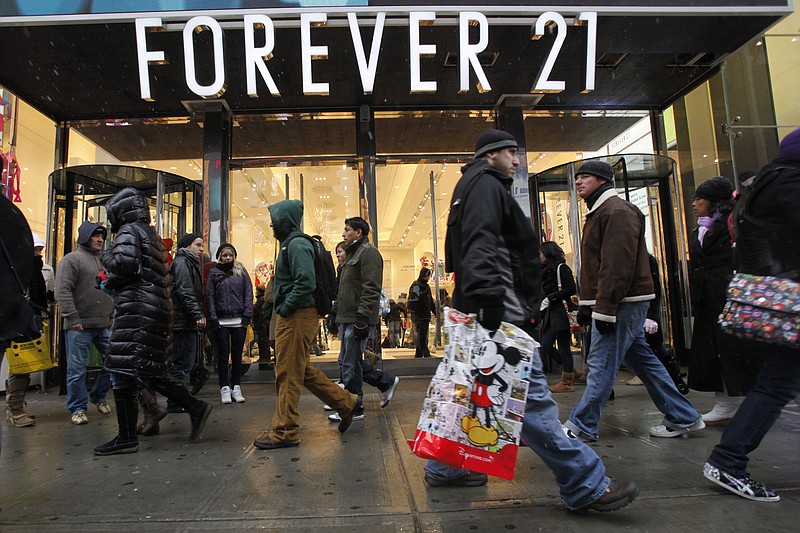

The Changs were indeed a unique success story, and Forever 21 was far from a run-of-the-mill family operation. At its peak, the retailer brought in more than $4 billion in annual sales and employed more than 43,000 people worldwide in hundreds of stores. Now it is leaving 40 countries and closing up to 199, or more than 30%, of its stores in the United States as part of its bankruptcy, and former employees and industry experts are pointing to the Changs' insular management style as a significant reason for the collapse. They cite disastrous real estate deals and the chain's bungled merchandising strategy in recent years.

"On the founder side, this hubris thing is pretty common, but it's particularly deadly if you've been successful for a long time," said Erik Gordon, a management expert at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business. "They didn't have a board of directors to give them a reality check, they didn't have equity analysts to give them a reality check."

He added: "You can live in your self-created bubble for a lot longer, but then the bubble pops."

The bankruptcy filing provides a rare glimpse inside a retailer that has been intensely secretive and privately held for decades. Six former employees, including three executives, also spoke to The New York Times about their experiences at Forever 21 on the condition of anonymity, citing nondisclosure agreements.

Forever 21's missteps, combined with industrywide changes in consumer tastes and shopping habits, will have far-reaching effects for thousands of people who work for the company, its vendors and malls. The chain says it will still operate hundreds of stores, along with its website. Through a spokeswoman, the Chang family declined to comment for this article.

Forever 21 - named because Do Won Chang considered 21 to be "the most enviable age" - was built on the idea of identifying apparel trends, then working with vendors to bring those products to stores quickly at cut-rate prices. From its early days, Do Won Chang, who is still the company's chief executive, oversaw landlord and vendor relationships while Jin Sook Chang led design and merchandising.

Former employees say that the top floor of the company's Los Angeles headquarters was viewed as Do Won Chang's world, where corporate strategy unfolded and people kept quiet outside his office, while the bottom floor was Jin Sook Chang's domain of buyers and planners, who showed their bags to security when leaving the building. Three former employees said that, as recently as this year, Do Won Chang was personally signing off on employee expenses and questioning executives about receipts for lunches or Uber rides.

The couple's daughters eventually joined the executive ranks. The oldest, Linda, is the executive vice president and has been viewed as Do Won Chang's successor; her sister, Esther, is vice president of merchandising.

The Changs never took Forever 21 public, unlike their biggest fast-fashion rivals, "declining numerous opportunities that would facilitate generational wealth," the filing said.

Their inner circle included another Korean-American couple: Alex Ok, Forever 21's president and a former supplier, and his wife, SeongEun Kim, who works in merchandising. Internally, some referred to Jin Sook Chang and SeongEun Kim Ok as the "Missuses," a powerful pair who directed the tens of thousands of styles that landed in Forever 21's bustling stores. The filing showed that the Chang family owned 99% of equity in the chain, while Alex Ok held 1%.

As the business expanded, the Changs struggled with their desire to hire experienced executives and their distrust of outsiders, five of the employees said. In recent years, they said, Forever 21 eagerly recruited experts to overhaul parts of the business, then later ignored their recommendations on everything from new technology to marketing.

Some were reminded of that dynamic after singer Ariana Grande filed a lawsuit against Forever 21 in September. The company's marketers had urged it to partner with Grande for a holiday campaign in 2014, according to two former employees, but management hired rapper Iggy Azalea instead. Now, Grande is far more popular, and Forever 21 is defending itself against claims that it used a look-alike model of the singer in online ads.

The Changs' Christian faith played a role in the way they ran the company. Forever 21's bright yellow shopping bags are stamped with "John 3:16," a reference to a Bible verse. Do Won Chang has said the verse "shows us how much God loves us," and hoped others would learn of that love. Former employees said Bibles were sometimes visible in conference rooms and on Do Won Chang's desk. It was not unusual for department leaders to have ties to the family or their church but no experience working for another retailer, employees said.

"Every once in a while, when we hired someone who had been there, we'd learn that they were never allowed to see the totality of the business performance and they were only given reporting on their specific sector," said Margaret Coblentz, a former e-commerce director at Charlotte Russe. Rivals saw Forever 21 "as both monolithic and inscrutable," she added.

But Forever 21 made its biggest mistakes in real estate. In the years before and after the recession, the company expanded aggressively and decided to open huge flagship stores, setting up in cavernous spaces once occupied by Mervyn's, the bankrupt department store, as well as Borders, Sears and Saks. Its former head of real estate told Bloomberg Businessweek in 2011 that "having really big stores has always been Mr. Chang's dream."

The stores became hard to fill with new merchandise, then turn over, however, and saddled Forever 21 with long leases just as technology was beginning to wreak havoc on American malls. Seven of the leases at the old Mervyn's stores were not set to expire until 2027 or 2028, which is longer than a typical lease, according to internal documents obtained by The New York Times.

In an interview conducted last month, when the company filed for bankruptcy, Linda Chang acknowledged issues with the larger stores. "Having to fill those boxes on top of having to deal with the complexities of expanding internationally did stress our merchant organization," she said.

She also cited shifts in mall traffic and the rise of e-commerce as challenges, and said that the bankruptcy was "a strategic move on our part."

Do Won Chang, who sought to sign each lease and design every store himself even as the count soared past 500, was loath to close even underperforming locations, and at times, would simply move a store to another spot in the same mall, two former employees said.

"Forever 21's problem is not the malls - it's that they didn't get out of the malls earlier," Gordon, the management expert, said. "If they want to point a finger, they need to stand in front of a mirror and point it at themselves."

The retailer also raced into expensive, massive new stores overseas without local expertise, as it surged from seven international stores in 2005 to 262 a decade later. Two employees said that the chain often did not understand local labor laws and made mistakes, like failing to recognize that customers in some European countries shopped for winter merchandise earlier in the year than American consumers. One employee said the chain moved into Germany without realizing stores in the country typically closed on Sundays. It didn't help that many of these areas were familiar turf for H&M, which is based in Sweden, and Zara, whose owner is in Spain.

Forever 21 said in the filing that most of its international locations were unprofitable as of 2015 and that its stores in Canada, Europe and Asia were losing an average of $10 million per month in the past year. Overall, the annual occupancy cost of Forever 21's stores was $450 million.

"They've gotten into categories and expression of fashion that are not closely aligned with their fast-fashion customer's preferences," said Mark A. Cohen, the director of retail studies at Columbia Business School. "They never built the intelligence into the business that would have cautioned them from this real estate orgy and would have kept them from the kind of exposure that they have now."

Yet even as its errors abroad became clear, Do Won Chang and his real estate counterparts bet on even more U.S. stores. An internal playbook from 2015 described the retailer's plans for a new strip mall chain called F21 Red that would target mothers under 35. Its $1.80 camisoles and $7.80 jeans were meant to swipe at the Irish retailer Primark, which entered the United States that year.

The playbook showed that six stores were already open, and that Forever 21 planned to open 35 more that year, including in regular malls, which was a surprise to the employees who had planned F21 Red. By 2017, several new F21 Red stores were posting sales that were around 50% below company projections, internal sales reports show.

That year, Forever 21 also introduced a beauty chain, Riley Rose, that was viewed as the company's next wave of growth and sought to capitalize on the boom in Korean skin care products. It was created by Linda and Esther Chang and called "ground-breaking" in the bankruptcy filing, which grouped its sales with the slumping international division.

While former employees praised the sisters' work ethic, they said that Riley Rose, which had 15 stores this year, was an expensive gamble in high-priced malls and struggled to maintain vendor relationships. The company told The Times last month that Riley Rose may end up as a store within Forever 21 locations. It has filed to reject leases for nine previously planned Riley Rose locations.

Jin Sook Chang's side of the business was also making errors with the sprawling store base. Merchandising was based on the previous year's sales, and Forever 21 bought too little inventory in 2017, then too much in 2018, the filing said. It also duplicated merchandise by designing for "styles" like weekend or work looks, rather than categories like tops or dresses.

Forever 21 had about 6,400 full-time employees and 26,400 part-time employees when it filed, numbers that will likely shrink throughout the bankruptcy process. Forever 21 said that it would change how it merchandises, winnow its operations to the United States, Mexico and Latin America, aim to increase e-commerce sales to more than just 16% of the business and take other cost-cutting measures. When it filed, the company owed $347 million to its vendors.

The Chang family will be listening to new voices. Its board of directors will grow from three members - Do Won Chang, Linda Chang and Alex Ok - to six, including Forever 21's former head of real estate, a lawyer and the former chief executive of Things Remembered. It also said that it had added several new managers in recent months, including a new chief financial officer. Do Won Chang remains the chief executive.

"Forever 21 has basically been a one-trick pony," Cohen said. "The founder and his wife did remarkably well until the business got too big for them to continue to do remarkably well by themselves."