‘All the Money in the World’

› Rating: R› Running time: 2 hours, 12 minutes

"The quality of mercy is not strained," Portia tells Shylock in "The Merchant of Venice." It is "twice blest; it blesseth him that gives and him that takes."

Billionaire J. Paul Getty would probably have disagreed with Shakespeare's take. A hoarder of women, art, antiquities - and most of all, money - Getty also might have taken issue with Portia's claim that mercy "becomes the throned monarch better than his crown." Portia delivers her mercy speech while successfully persuading Shylock not to take a pound of flesh. She would have had a far tougher time with Getty.

"All the Money in the World" is a story of towering greed and the absence of mercy, and an ideal 21st-century morality tale. It's about money and families and the ties that bind and cut, although because it was directed by Ridley Scott there isn't a jot of sentimentalism gumming the works. In July 1973, John Paul Getty III (known as Paul), the elder Getty's 16-year-old grandson, was snatched off a street in Rome. His kidnappers demanded $17 million in ransom, telling Paul's mother, "Get it from London." It was a reference to Getty Sr., who in turn responded, "If I pay one penny now, I'll have 14 kidnapped grandchildren," a kiss-off heard around the world.

Scott sets the scene quickly with a somewhat phantasmagoric meander through Rome's crowded streets. It's night, and pretty, boyish Paul (Charlie Plummer) is savoring la dolce vita, floating past the city's flesh and marble beauties and its swarms of catcalling, hustling paparazzi. There's sensuousness to Paul's drift, which, as the camera silkily slips alongside him, suggests a casual luxurious attitude toward life, of being free to do anything, go anywhere, say anything. He's kissed by fortune but also by youth. And when a streetwalker calls him baby and he smiles, you see just how young. Within seconds he's been kidnapped.

"All the Money in the World" revs up beautifully, first as a thriller. But while the kidnapping is the movie's main event, it is only part of a story that is, by turns, a sordid, desperate and anguished tragedy about money.

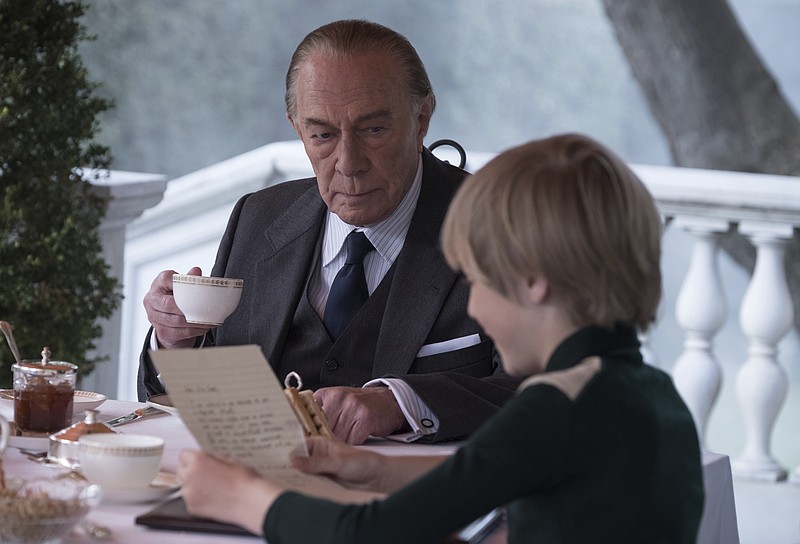

When Paul is kidnapped, Getty Sr. (Christopher Plummer) has already amassed a fortune, one partly pumped out of oil fields both in the United States and in the Middle East. (The Plummers are not related.) He lives alone in crepuscular gloom in Sutton Place, a manor house built by a favorite courtier of Henry VIII. There, amid miles of rooms adorned with gilt-framed masterworks, Getty Sr. closely monitors the stock information on the disgorging ticker tape that's both his leash and lifeline.

Scott is a virtuoso of obsession, of men and women possessed. He likes darkness, pictorially and of the soul, and in Getty Sr. he has a magnificent specimen. And in Plummer he has a great actor giving a performance with a singular asterisk: In early November, with the movie already done, Scott hired Plummer to replace Kevin Spacey, who has been accused of sexual misconduct. It was a bold move, an extreme variation on leaving a performance on the cutting-room floor. The 88-year-old Plummer isn't fully persuasive when briefly playing the younger Getty Sr., even in long shot. But his performance is so dominating, so magnetic and monstrous that it doesn't matter.

Like many contemporary movies, this one kinks up its timeline. After Paul is kidnapped, the scene shifts to Saudi Arabia in 1948, where Getty Sr. is laying the foundation for an even greater fortune. Written by David Scarpa - working from John Pearson's 1995 book "Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortune and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty" - the movie continues to jump around, filling in the backstory while deepening the atmosphere and gathering the dramatis personae. One intimate scene takes place in the 1960s, where Paul's mother, Gail (Michelle Williams, warmth incarnate), and father, Getty Jr. (Andrew Buchan), are going broke with four boisterous young children.

By the time Paul is kidnapped, his nuclear family has imploded; Getty Jr. is lost in an opium cloud and Gail is living in Rome. Much of the movie involves the drama of the kidnapping, which unfolds in separate, increasingly tightly woven-together lines of action. Taken by a ragtag criminal gang, Paul is stashed in a desolate farmhouse, where his closest keeper becomes Cinquanta (Romain Duris, a charismatically feral presence).

In Rome, Gail struggles with the kidnappers, police and paparazzi while trying to interest Getty Sr. in his grandson. Getty Sr. continues counting out his money, only reluctantly calling in the cavalry, a security specialist, Fletcher (a very fine Mark Wahlberg).

Scott conjures up entire worlds and sensibilities with visual precision, adding detail even when going for sweep. Each new scene adds another layer of meaning, thickening the slow-building sense of dread: the men in billowing white robes on oil-rich land waiting for Getty Sr., a master of the universe who arrives in a demonically belching train. Gail and Getty Jr., anxiously presenting their young family to Getty Sr. like paupers bowing down before the lord of the realm. As the story shifts from farmhouse to manor, from the kidnappers to Getty Sr. (each side armed, impatient, brutal), a parallelism develops and it becomes clear that he took his family hostage long before the kidnapping.

Plummer can be an aloof, fairly cool screen presence and he chills Getty Sr. with cruel glints, funereal insinuation and a controlled, withholding physicality. A lot of actors soften their heavies, as if nervously asserting their own humanity. With Scott, Plummer instead creates a rapacious man whose hunger for wealth and power (and more money, always more) has hollowed him out and whose fatherly touch, at its most consuming, brings to mind Goya's painting of Saturn eating his son. The horror of Getty Sr. is that he is never less than human, but that he's hoarded everything, including every last vestige of love, for himself. It's a magnificent portrait of self-annihilation.

At one point in the movie, Getty Sr. does pull out his wallet, buying a masterpiece while Paul continues to languish with his kidnappers, an ordeal that grows more frightening and byzantine as the clock winds down. Gail and Fletcher are struggling to free Paul, an effort that finds them often grappling with Getty Sr. His interest in Paul rises and falls, much like the stock market does.

He has become famous for his status as the wealthiest man in the world, prominence that he clings to, much like his money. He has filled his manor house with priceless objects, turning statues and paintings into fetishes. He has earned so much, spent so much and, in doing so, insured that he and everyone else have lost.