In October 1969, Walter Cronkite brought Chattanooga into the spotlight by awarding it the title of "The Dirtiest City in America." Now, 47 years of work and rebranding later, titles earned are optimistic, inspiring and flattering, rather than fear-inducing.

The city's renaissance is not simply due to its technological advancements, the big businesses that have moved in and the tourists who flock to local attractions. It is about the phrase that diverse local populations, from Lookout Mountain residents to Millennials in the Innovation District to officials with Gestamp or Volkswagen, utter: "There's just something about Chattanooga."

Many cities redeem themselves in terms of quality of life or opportunity, but few create as unique an atmosphere as Chattanooga. The hidden thread that pulls it all together is not so hidden, says Peggy Townsend, a longtime resident, arts advocate and business owner. It's the uniquely artistic sense of self the city has developed, which lends it own type of cohesiveness. A celebration of the arts is but one arm of that identity, but it is an important one, and it certainly was not accidental.

"Even if you are not directly paying attention to public art specifically it is creating an atmosphere of livability and vibrancy," says Kathleen Nolte, program officer for the Lyndhurst Foundation.

The nonprofit founded on Coca-Cola dollars is a large contributor to community development and quality of life endeavors across the country, from preserving green space to enhancing education, and public art projects across the Scenic City account for a sizable chunk. From 2005-2015, Lyndhurst's online records of the grants it gave show that approximately $11.5 million went to organizations, events and infrastructure directly tied to the arts. Even without the millions more Lyndhurst gave to the 21st Century Waterfront Project - an overall $21 million revitalization program in which 1 percent was set aside for art: the ambiance-enhancing lights on the Chattanooga Pier, the Native American art installation at the Passage, and the First Street Sculpture Garden - that accounts for more than 11 percent of all the grants given during that period. "Even if you don't notice it [public art] every day, there's something that just makes it really nice to be around. It's there and it's a feeling, whether you recognize it intentionally or not," Nolte says.

Townsend has been a part of art councils across the city since the first one began in 2003, and served as the first director of Public Art Chattanooga, which helped bring art to the city's main stage through the 100 permanent and 42 temporary works of art placed throughout the city, as well as multiple privately supported programs it now manages. "There have been people working, doing this work, for decades. It's about aesthetics and a sense of placemaking. Art is one ingredient in a big soup, but it's a big piece," she says.

The history of art in Chattanooga is largely a recent one, but it can also be traced back to the inception of the Riverwalk in the late 1980s and 1990s, says River City Company Communications Director Amy Donahue. When the Trust for Public Land partnered with the city and local organizations including Lyndhurst to begin laying the groundwork for the Riverwalk, art was always meant to be part of the equation.

"It took a lot of the smart leaders and art advocates making sure that art was part of the concepts coming. It morphed with our revitalization efforts because individuals kept it a part of the conversation," Donahue says. "As we all sort of claim the Chattanooga way of rethinking an area based on art, it's built into our collective community operating system because of them."

Donahue admits public art can be difficult to quantify in terms of economic impact. However, she says, simply looking at the revitalization that happened in much of the areas where large art installments were introduced begins to paint the picture of its deeper meaning in the city's social consciousness.

In 2007, when CreateHere moved into Chattanooga's Southside neighborhood, defined by River City as being from 12th to 20th streets, between I-27 and Madison Street, the community was considered a no-go by many. It had become a place of abandoned and dilapidated buildings, dwindling property values and not much else save for some longtime residents. Countless grants over CreateHere's five-year lifespan - with Lyndhurst funneling more than $4 million to the organization - helped turn the tide. Artists began moving in thanks to ArtsMove grants which offered up to $2,500 in moving expenses, as well as up to $15,000 off an artist's mortgage if he or she agreed to stay in a home in a targeted neighborhood - the Southside being a primary one - for at least five years.

In keeping with its burgeoning artist persona, sculptures were installed along Main Street, the main thoroughfare. A neighborhood festival was birthed - Mainx24, which will celebrate its 10th year this December - bringing life and visitors to the streets. Development followed. Today, the Southside is home to an ever-increasing number of apartments, condos and townhouses, with some renting for as much as $740 a month for 350 square feet.

"Public art really was the first catalyst that got people feeling comfortable walking around down [on Main Street]," Townsend is quoted in a Times Free Press article as saying at that time. "It's been a revitalization tool, clearly."

The impact art can have has trickled over elsewhere in other similar ways, says Donahue. "[Public art is] intangible in some ways, but it adds into the overall factors of unique sense of space and quality of life, and of course those are big economic drivers when you're looking at relocation and business development," she says. "One of the things that we talk about is when VW was looking at different areas when they announced their big plan, they did it at the Hunter. And the big quote of the day that they gave was about how Chattanooga was able to make the intangibles tangible; this quality of life, this unique sense of space."

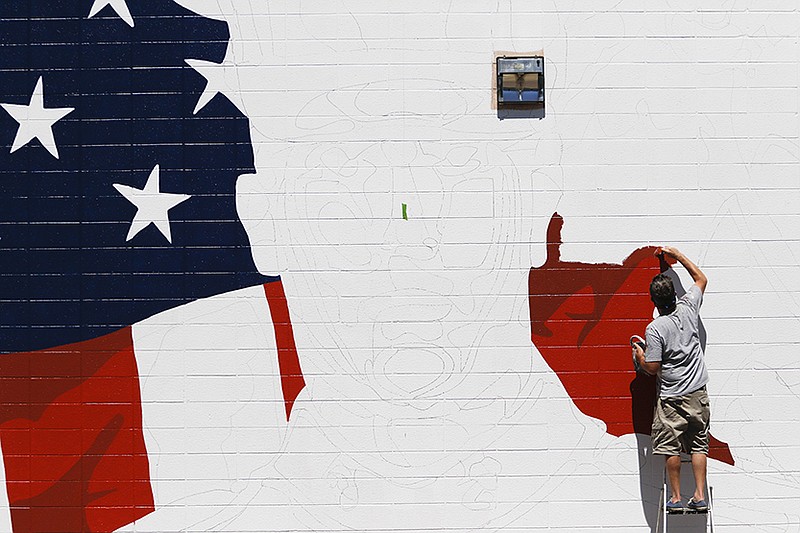

A unique space can come in many forms, from the Sculpture Fields at Montague Park to the M.L. King District Mural completed in January on the AT&T building; even simply the architectural design of the riverfront along Ross's Landing. As with the riverfront and the Southside, the M.L. King District Mural looks poised to become one part of a puzzle with an economic impact. Organized by Public Art Chattanooga while Townsend served as part-time director (she resigned in February after six years at the helm), the 42,179-square-foot mural sits in a long-suffering stretch of the city where, for more than 40 years, most motorists have used the corridor to get to where they were going - which likely wasn't along M.L. King Boulevard. But now, businesses are moving back in, and the city has proposed a traffic-calming plan meant to encourage people to stop, shop, dine and walk along the road that once funneled them away from a decaying urban core.

"[The city] took a building that is probably always going to be there, because there is so much infrastructure, that doesn't necessarily give anything to the public realm. By painting a mural on it, we can make it a jewel of the boulevard and [it] was a great gap that has been filled," Donahue says. "Again, it adds to the unique sense of place and the vibrancy of the boulevard, change that is already underway there. And I think that is what we can continue to do: find gaps and figure out how to fill them either short- or long-term."

Katelyn Kirnie, new director of Public Art Chattanooga, says that in addition to filling spaces, public art can serve as a unifier and conversation starter among the diverse residents who come in contact with it.

"It's about creating opportunities for interaction that spark dialogue," she says. "From the businessman to the homeless person, every single person in the city has the opportunity to experience it."

As with anything, though, that dialogue is not all positive. For example, in 2011, in the midst of the Great Recession, after the city had slashed Public Art Chattanooga's funding from $100,000 to $20,000 (though by accounts from Townsend and others at that time, most of the budget came from private sources), the City Council debated whether even that was too much. Representatives Jack Benson, Pam Ladd and Deborah Scott - who all represented constituents outside of the urban core, where a majority of public arts projects were concentrated - cited feedback from their districts in questioning the expenditure, which Ladd called a "hot button" issue. Ultimately, since it had already been budgeted, a majority of the council voted in favor of the funding.

One commentor using the online ID "Allison12" wrote in response to the news on the Times Free Press' site, "I have no obligation to pay taxes to prop up artists or art in general. It is a ridiculous notion that any government can levy taxes to fund an art collection. Understand, that our current city council, as a majority, does believe that taxing for art is appropriate. Only in Disney Land."

But even then, the economic impact of Chattanooga's art efforts were beginning to be recognized. In 2010, Jefferson Heights, a Southside neighborhood where many artists had moved in thanks to grants, won an excellence award from the Chattanooga-Hamilton Regional Planning Agency for the more than $12 million in direct investment it had brought the city. And now, with multiple Public Art Chattanooga projects such as Art in the Neighborhoods, which is focused on beautification and improved quality of life through art across the Scenic City's residential areas, art's role in city growth is becoming more institutionalized.

Over the next month, Kirnie says she hopes Public Art Chattanooga's next project, Blue Trees, will continue to encourage dialogue between residents. The environmental art installation, a passion project of artist Konstantin Dimoplous, will occur across the city aims to raise awareness for the importance of environmental consciousness by highlighting trees in urban settings. To do so, Kirnie is working with the city's arborist and using an organic, nontoxic paint to color tree trunks across the city in the vibrant color.

"It's not just about making sure we have high-quality art, it's about making sure we are broad and dynamic in supporting a variety of art forms," she says.

She adds that it's important to employ that same mentality to the overall process, gathering input from the stakeholders - the community who will come in contact with it - not just focusing on the final product. For example, the M.L. King District Mural was created based on results from multiple visioning sessions with residents from across the city. Such a process only enhances the final product, she says, and that is the sort of project process Kirnie intends to implement more of as she grows in her role as director for Public Art Chattanooga, which she took on just after the mural was unveiled.

"We've got some good examples of where we've done that, and we've got some examples where that hasn't happened and things have been added later," Townsend says. "And, you know, both are fine, but personally I'd love to see more opportunities where the public artists are brought in really early to assist with the overall design."

"It engages creative thinkers to animate dead spaces," says Kirnie. "It's not just about the art - it ends up being about the art - but it's about the process, and that's ideal."

She cites River City's recent Passageways project, unveiled in August, as an example of space animation and artist involvement. For that installation, which will animate alleyways around the city for at least a year, artists were shown the spaces and asked to come up with ways to make them more inviting.

"It's about, rather than picking the spot for the sculpture, saying 'Hey, we have this big issue, what could an artist do to solve this problem?'" she explains. " And then not confining them to one spot, but saying 'Here is this space, we have this issue, come up with a creative solution that is also artwork.' And that provides an interesting opportunity to build on the unique identity of our spaces.

"You can have a beautifully designed space without knowing what city you're in. But if you design something truly original, truly unique to the artist, it becomes truly unique to Chattanooga."

Another such project is the upcoming Blue Goose Hollow sculpture, by renowned sculptor Albert Paley, slated for the latest 3-mile extension of the Riverwalk through St. Elmo which opened in August.

"It's going to be an incredible piece," Nolte says of the sculpture, which was made possible partially through Lyndhurst's funding and partnership with Public Art Chattanooga.

Oftentimes, the road from the initial concept to finished product is a long one, as it was for Montague Park founder, curator and sculptor John Henry. "My first discussions were with then-mayor Bob Corker," he says of the sculpture fields which opened approximately a year ago. "I said, 'Give [the lot] to me, I'll do something with it.' And three administrations later, that finally happened."

After $1.2 million in investment and several thousand truckloads of dirt, the 33-acre park in the 1100 block of East 23rd Street now welcomes visitors seven days a week to wander among dozens of sculptures, but even now, the sculpture field is not complete, Henry says. He sees another three years, possibly more, before the park reaches its full artistic potential: dozens more sculptures, improved landscaping, and a visitors center. "There are just so many great spaces and backdrops that are really what sculpture needs," he says of the park's potential.

However, potential can't feed an artist or allow them to make a living off of his or her craft. And on that front, Henry cautions, Chattanooga has not come as far.

"The one problem I see is that we paid a lot of attention to getting artists here and paid a lot to attract artists, but artists have to have a market, and that really hasn't happened yet," he says. "We need a bigger, broader spectrum of places where artists can really capitalize on what they're doing."

One element that should grow is the number of art fairs, as well as other options for local artists to represent themselves to the public at large, rather than only curating the art without the artist, he says.

"We're already making the art, but it has to go somewhere and it has to be paid for," Henry explains. "Artists need to make a living - and be making a living with their art, not having to pump gas somewhere. We need to cultivate that marketplace. And that could happen."

Townsend says some of that needed growth may come naturally, as the emphasis on art in new projects throughout the city becomes more prominent. "The more art projects you have, obviously, the more artists are able to make a living," she says.

And cultivating a wide variety of mediums will only further the cause.

"I think Chattanooga will really begin to unfold the canvas that it is for public art," says Henry. "Chattanooga is changing, and pretty rapidly. There's new buildings going up in almost every part of the city that are the perfect setting to further public art. The future is bright, we just need to roll up our sleeves and continue to make it happen."