They say it doesn't matter whether you're in Chicago, San Francisco or London; when you tell people you're from Chattanooga, they'll immediately begin to sing or think about Glenn Miller's 1941 hit song, "Chattanooga Choo Choo."

For Justin Strickland, author of the book "Chattanooga's Terminal Station" and self-proclaimed train nerd, that moment came in 2016 while riding the Amtrak from New York City to Albany.

Upon settling down in the train's café car, Strickland struck up a conversation with a stranger seated across from him, who, true to legend, began scatting the iconic tune the moment Strickland mentioned he was from Chattanooga.

"He was actually a member of the New York Philharmonic," Strickland laughs, describing how the surprise rendition nearly threw him from his seat. "He was a music history major, and that's one of the things they learned. It's just amazing that on a train on the Hudson River is when I heard someone humming the song."

Sadly, Strickland continues, his voice growing somber, he believes that instant recognition of the city's railroad heritage is becoming less common.

"It's starting to become more and more that you talk about Chattanooga and people don't even connect the fact that we're a railroad town even today," he laments.

Though most people still know about the famed "Chattanooga Choo Choo" song and can even recite the lyrics backwards and forwards, Strickland believes fewer people truly know why the song was so popular and understand just how important it was - and still is - for the city.

While public-private partnerships, superior outdoor amenities and gigabit internet service have been largely credited for Chattanooga's transformation and continued advancement from a declining industrial town to the thriving city it is today, Strickland believes Miller's hit song was also a large contributor to the area's metamorphosis.

Without the name recognition afforded by the song, he argues, the Chattanooga Choo Choo hotel would not have achieved the renown it obtained when owners adopted the moniker and turned the historic Terminal Station into a tourist attraction in 1972.

"Without Glenn Miller and his song, would we even be on the map right now? I don't think we would," Strickland says. "That song gave us a future when Chattanooga may not have had a future. ... I think we owe everything in Chattanooga to Mack Gordon and Harry Warren, who wrote [and composed] the song."

The WORDS that Inspired a Generation

The last few lines of the iconic 1941 song were particularly powerful for World War II soldiers, though many haven't realized just how intertwined the song and the global conflict were, says Strickland.

Did you know?

Less than a year after the song’s recording — and after already selling 1.2 million copies — “Chattanooga Choo Choo” became the first song ever to receive a gold record. Contrary to popular belief, however, the song itself was not sung by Glenn Miller. The vocals were performed by Tex Beneke and the Modernaires. Miller was the bandleader.

Coincidentally, "Chattanooga Choo Choo" was declared the No. 1 song across the country exactly seven months after its recording - on Dec. 7, 1941, the same day Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, killing more than 2,000 American soldiers and solidifying the nation's decision to enter the ongoing war.

"That absolutely blew my mind," Strickland says. "It's just a little piece of irony that a song that speaks of traveling home became the No. 1 song in America on the day that was one of the darkest days of our history."

As the U.S. began relying on the railroads to transport troops and supplies to fight against the Axis powers, the song started to take on a military connotation for soldiers.

"Almost all of them had to travel by train in order to be able to get to airfields or to naval shipyards before they were shipped out overseas," Strickland explains.

For those longing for the day the fighting would end so they could return to their loved ones, the final stanza of the song was a bright spot, as it describes the passenger being reunited with a special someone and promising never to leave - or, in this case, be deployed - ever again:

There's gonna be a certain party at the station

Satin and lace, I used to call funny face

She's gonna cry until I tell her that I'll never roam

So Chattanooga Choo Choo, won't you choo choo me home?

"It gave the soldiers who were listening to the song in this period of time something to look forward to upon returning back home," says regional historian and WWII re-enactor Charles Googe.

The song's role as a beacon of light is fairly well documented throughout the war years, Googe continues.

In 1944, the song was rerecorded and distributed to soldiers on Victory Discs, records provided to U.S. military personnel by Armed Forces Radio at no cost. It bolstered spirits and nourished national pride alongside other V-Disc recordings like "Baby, Won't You Please Come Home" and "Gee, It's Good to Hold You."

Eager for a more ever-present reminder of home or otherwise inspired by the song, some soldiers branded their weapons and vehicles with the words "Chattanooga Choo Choo." Archived photos show a crew in North Africa sitting on an M4 Sherman tank with the title of the song stenciled on its side, while another shows a bomber crew posed in front of a B-24 Liberator aircraft emblazoned with "Chattanooga Choo Choo: The Flying Boxcar."

The SOUNDS that Birthed a Sensation

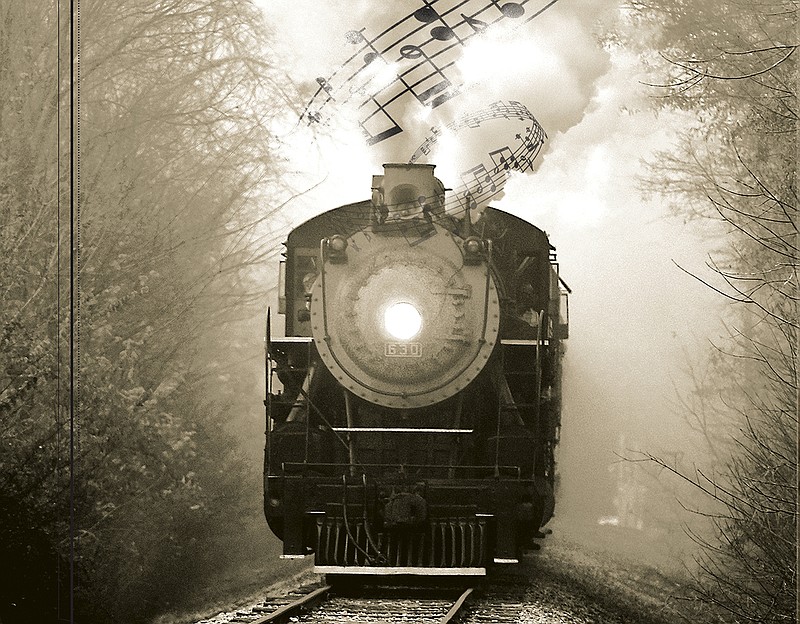

Travis Gordon brushes a few beads of sweat from his forehead with a soot-tinged sleeve as the Southern 630 steam engine barrels along Missionary Ridge. Behind him, in the adjoining passenger cars, riders lounge comfortably and children begin to doze off, lulled to sleep by the gentle rocking of the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum train. But here, up front, Gordon and his fellow locomotive engineer, Nicholas Colman, are fully alert, their ears tuned to each hiss and whine of the early-1900s machine as they take turns feeding it shovelfuls of coal.

Wiping a few more droplets from his face, Gordon again rests his foot on a pedal that opens the heavy metal doors to the engine's firebox with a pressurized pft! A wave of heat billows from the flames within, burning at a temperature of approximately 2,500 degrees.

Operating the 100-ton engine takes more than just an intricate knowledge of pressure systems and external combustion, Colman says, watching his partner toss more coal into the fire with a clank! of the shovel. It also takes a sense of rhythm, he explains, making it understandable why composers might look to the machines for inspiration.

"A lot of musicians work on these things because there's an art to running them," says Colman, who was a professional musician in Nashville prior to his conversion to locomotives in 2011.

Gordon nods in agreement as he lifts his foot from the pedal, causing the pressurized system to release the butterfly doors with a tssss! He himself was in the jazz band while attending Northwest Whitfield High School, he says as he lets the doors swing shut with a loud clunk!

"There's a lot of science going on, but it's all about feel," Colman continues. "Just about everything in here you're going to feel or hear. So you'll know really quick when something isn't running right or when something's breaking."

When everything is running smoothly, the entire experience is auditorily pleasing, he adds, and as the engineers continue to work, a song begins to form.

Pft! Clank! Tssssss! Clunk!

Pft! Clank! Tssssss! Clunk!

Pardon me, boy ...

Is that the Chattanooga Choo Choo ...

While it's unlikely the songwriters had the rhythm of the fire door in mind while composing the 1941 hit, other acoustic elements of the steam engine are purposefully embedded into the music, Colman and Gordon say.

Seriously, is that the Chattanooga Choo Choo?

Interestingly enough, the train described in the song never existed. The name “Chattanooga Choo Choo” was likely coined by songwriters for alliteration, Strickland says.In fact, the lyricist, Mack Gordon, was inspired to write the song while riding the Birmingham Special, which passed through many of the locations mentioned (though one couldn’t have had “ham ‘n’ eggs in Carolina” aboard, as it never passed through the state).“But Bristol Choo Choo doesn’t quite have the same ring to it, does it?” Strickland laughs.

At the beginning of Glenn Miller's original song, for example, a drum beats in sync with a series of short honks from a saxophone, creating a staccato rhythm that slowly gains speed as the song begins. The tempo calls to memory the chuh chuh chuh sound produced by the rods connecting the train's wheels as the machine begins to gain momentum, Colman says. The noise, called "stack talk," is one of the many sounds engineers listen for to determine what kinds of adjustments the locomotive needs.

"That song is literally mimicking the rhythm of a train," Colman says. "[The writers] obviously took their time and did their research."

The most prominent train sound illustrated in the 1941 song, of course, is that of a train whistle, says Laud Vaught, instructor and coordinator of the Music Resource Center at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. Using a close harmony consisting of major sixth chords, he explains, the band produces distinct whistle-like tunes with a piano, trumpets and trombones.

Placed at the beginning of the song, the blare of the whistle triggered visions of adventure and glamour for the era's listeners, who were familiar with the luxury provided by the mode of transportation, Vaught believes.

Even those who couldn't afford to ride the train themselves would have been familiar with the unmistakable whine of the whistle, which may have served as an ever-present soundtrack of hope for those saving up their pennies while dreaming of their escape from their mundane responsibilities or small towns.

"Steam locomotives and train travel were such a common thing back then that was so very easily relatable," says Colman, pointing back to lyrics like "Dinner in the diner; Nothing could be finer" that hint at that luxury.

Gordon gives another nod as the train slows to a stop, offering one final compliment for the songwriters. "These guys really knew what they were doing," he says.

The RENDITIONS that Continue the Legacy

Like most, Charles Googe grew up hearing the iconic "Chattanooga Choo Choo" song. But when he heard Elton John perform a rendition of the classic during a concert at McKenzie Arena in 2010, he began to see the tune in a whole new light.

Pounding the keys on his piano and answering the "Pardon me, boy?" question with a hearty "Ohh yeah!" the British singer thrilled the local audience, but it wasn't just the impressive vocal work that captured Googe's interest. For the young historian, the rendition spoke volumes about the longevity and relevance of the song itself.

"To hear it being played in concert really just solidified how important the song was to the musical community," Googe says. "Here in Chattanooga, we tend to see it as a source of local pride, but to hear it from someone who is not even originally from the United States really hit home the significance."

Since Glenn Miller's original version was released in 1941, the song has been covered by more than 40 recording artists, which doesn't count the impromptu adaptations celebrities like Elton John and Usher have performed as a special treat for local concertgoers. It also doesn't count the numerous television shows from "M*A*S*H" to "Family Guy" that have incorporated the song into an episode in one way or another.

Each new recording provides a different experience for listeners, Googe says, as each is imbued with the stylings of its era, the personality of its artist, and his or her relationship with the railroad and the original song.

"I think it really speaks to the universal acceptance of the song, not only as part of Chattanooga's culture, but also as part of American pop culture," Googe says. "The style in which it's played will change over time and people's perception of the song may change based on that, but it still is the constant Chattanooga Choo Choo."

Here are a couple of our favorite renditions that are definitely worth a listen.

The Andrews Sisters (1941)

Singing in close harmony and adding a few prelude lyrics of their own, this world-renowned vocalist trio delivers a captivating boogie-woogie version of "Chattanooga Choo Choo" that is still a favorite for many today.

Carmen Miranda (1942)

Decked out in a flamboyant dress and one of her trademark fruit hats, Carmen Miranda, remembered by many as the Chiquita Banana Girl, sings "Chattanooga Choo Choo" in Portuguese while samba dancing in the musical comedy film "Springtime in the Rockies."

Bill Haley & His Comets (1954)

Bill Haley's early rock 'n' roll take on the "really crazy Tennessee excursion" includes backup singers in close harmony along with a pretty rockin' guitar intro.

Ray Charles (1957)

Slower and calmer than earlier iterations of the song, this blues rendition by "The Genius" himself adds a bit of soul to the song, imbuing it with an eerily beautiful sense of wistful yearning.

Harpers Bizarre (1967)

This adaptation by sunshine pop band Harpers Bizarre sets itself apart by keeping many of the train-sounding elements from Glenn Miller's original recording while implementing smooth yet upbeat vocals that practically scream Simon & Garfunkel.

George Benson (1968)

This instrumental jazz take on the 1941 hit incorporates a light yet energetic rhythm complete with harmonica that makes for easy listening.

Butterfly Records (1978)

If you liked The Andrews Sisters' take on "Chattanooga Choo Choo" but thought it needed a funky beat and some electronic dance music, this disco record label's reimagining on its album "Tuxedo Junction" is sure to be a treat.

Harry Connick Jr. (2001)

This quick-paced instrumental take on the song masterfully mimics the sounds and pacing of a train using only a piano.

» Click here for a playlist of these renditions and more.