Vascular surgeon Chris LeSar is a self-proclaimed tech junkie who says technology isn't just an asset to his medical practice - it's essential.

He has increasingly integrated technology into his work as medicine becomes more complex and the federal government penalizes providers who don't adopt electronic health records. But he also acknowledges the potential downsides of tech. Now, he says, it's not just the patient and the doctor in the exam room. It's the patient, the doctor and the computer.

"I never liked that. When I'm talking to someone, I want to look them in the eye and say, 'Hey, this is what's going on.' I need that personal connection," LeSar says. "I go to the doctor, too."

And some physicians are not so quick to adapt. LeSar recalls a time when he was completing an electronic health records training, and a doctor beside him was so frustrated he just gave up.

"That's what happens. These technology things push physicians out," he says. "For some older doctors, it's a foreign language. You have to learn it, and some people can't."

In her new book, "Resilient Threads: Weaving Joy and Meaning into Well-Being," Dr. Mukta Panda touches on the toll technology can take on health care professionals.

"The requirements for electronic health records can be so frustrating. I hear this all the time from students, residents, and even faculty: 'I have to get my notes done!' I tell them I sometimes feel like screaming that I can't take this (electronic health records) anymore," writes Panda, a professor and assistant dean at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine at Chattanooga.

Electronic health records are frequently cited as a source of frustration among medical providers. Physicians across all specialties gave the usability of current electronic health record systems an "F" grade, according to a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in November. That study also found a strong relationship between health record usability and the odds of physician burnout.

Another study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine found that emergency department physicians spend significantly more time entering data into electronic medical records than on any other activity, and performed nearly 4,000 mouse clicks during a busy 10-hour shift.

It's not just health records that pose a problem. Communication within the hospital can be equally frustrating, Panda says.

"One resident told me, 'I am carrying six pagers on my belt. I'm completely stressed and burned out,'" she says.

In her role as dean for well-being and medical student education, Panda spends much of her time teaching and mentoring residents - young doctors in training - on how to balance technology with patient care while remembering to take care of themselves.

She also helped launch LifeBridge, a physician wellness program from the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Medical Society. The program offers medical society members up to six free sessions per year with a therapist. Sessions are totally confidential, so doctors don't have to worry that seeking help might affect their credentials or license.

"Training in medical school onwards mainly focuses on disease management. We seldom acknowledge that we, the caregivers, are people like our patients," Panda says.

Dr. Colleen Schmitt, the medical society's immediate past president, says a number of physicians, residents and medical students have accessed services since LifeBridge began in 2018.

"If the program can lead toward prolonging the life of a practice, just that by itself would really serve a wonderful role in the community, because we don't want to lose physicians to retirement, or worse," Schmitt says. "You don't want something like electronic health records to push somebody out of a career."

Schmitt, a gastroenterologist at Galen Medical Group, says that although electronic records aren't perfect and can be frustrating, they ultimately improve patient care. Providers can access records offsite, patients can view test results on their own, and having more complete records all in one place gives a better patient history, which can facilitate a diagnosis and prevent unnecessary, costly tests.

"If a patient calls and says, 'This antibiotic was supposed to be sent in,' or a nurse has a question about a lab, I can access the lab and look at all the results from the other providers in our group. So it saves time and money," she says. For Schmitt, the challenge is knowing when to "switch it off."

"The work is always accessible to you, and I don't think that's healthy," she says.

Schmitt works with a colleague whose role is to take notes and plug them into the electronic health record so that she can spend time focused on the patient.

"It increased my efficiency, and it helped with the personability of the visit," she says. "I did not want to have my back to the patient. Exam rooms are built for performing a physical exam.You can't be touching the patient with two hands on the keyboard."

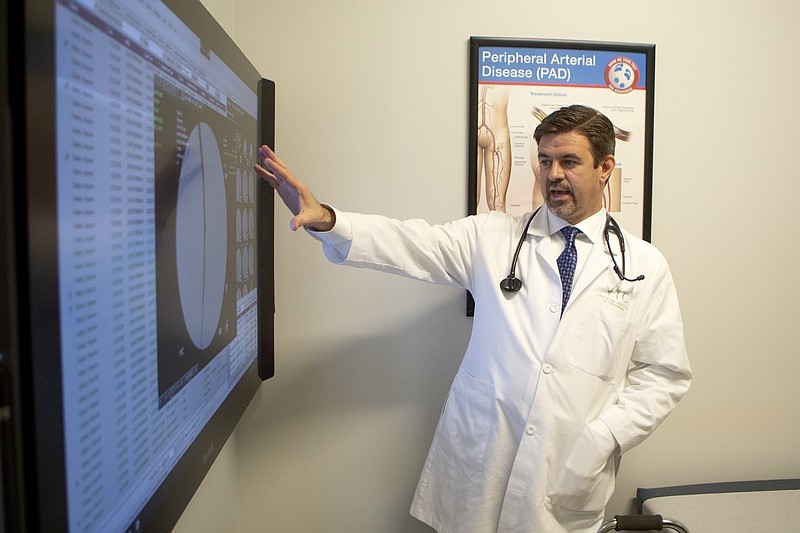

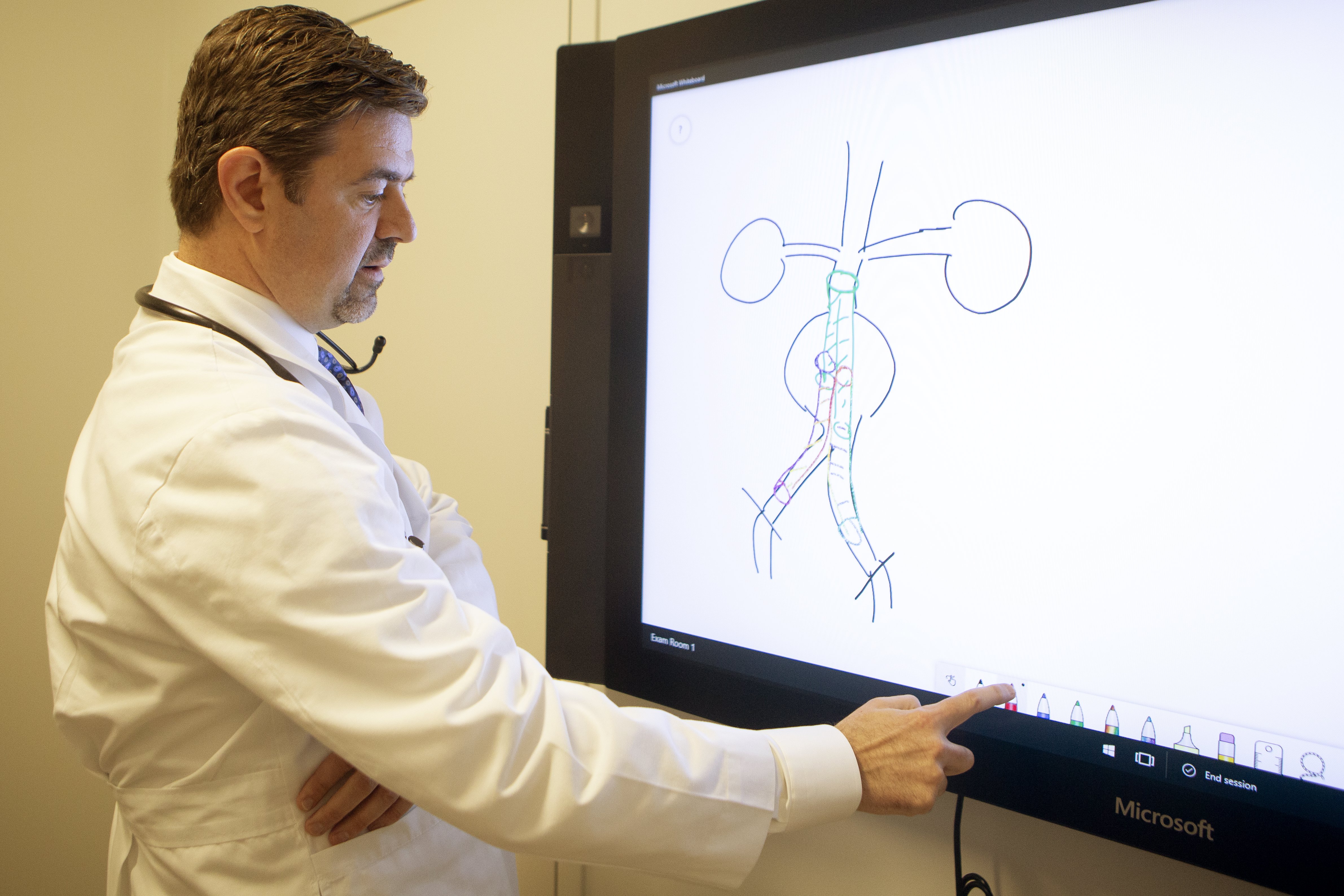

LeSar says technology drives the therapies that he uses as well as the patient experience. Each exam room in his main office off Lifestyle Way in East Brainerd has a 55-inch monitor that integrates all aspects of a patient's electronic medical record. The technology allows him to pull up health records in front of a patient - such as an ultrasound taken that day compared to one taken a year ago - and walk through key information together. He's also able to draw on the monitors to illustrate complex procedures so patients know what to expect during surgery.

"That's really powerful when you're looking at someone's blocked artery, and they had a middle or low-risk blockage last year, and it's now in the middle or high-risk," he says.

As a doctor and medical educator, Panda has fought to return human touch to an increasingly impersonal health care system where new, cutting-edge technology and treatments are often the first priority.

"What brought me to medicine was the opportunity to build a human connection with another person," she says. "Get to know the patient a little bit more. Who is that human being who's having a disease, rather than a disease?"

In February, a group of residents gathered for a class at Erlanger Medical Center. They pretended to be patients during discharge, and Panda assigned them various obstacles patients may face once leaving the hospital: no transportation, uninsured, low income. She was having them "walk a mile in a patient's shoes" to highlight the importance of empathy in medicine.

"As I have gone through this journey myself, something that I have really, really learned the hard way many times is to be kind to myself, and that's why I promote the idea of self care," she says. "It's an interesting time in health care. To me, it is still the best vocation. And I have hope. I have a lot of hope."

Going digital

In 2017, Erlanger Health System completed the transition of its medical records to EPIC, the the most popular electronic health records software for acute care hospitals in the United States. Erlanger invested $100 million to rebuild its IT infrastructure from the ground up. At the peak of implementation, Erlanger had 150 employees dedicated to the installation and replaced about 5,000 computers.In 2019, CHI Memorial switched its electronic health record system to EPIC. The move cost Memorial more than $67 million and took 18 months of intense preparation and about 60,000 hours of training across the health system.Parkridge Health System already has its own electronic health care records system, but it is proprietary, shared with all the 177 hospitals owned by parent company HCA.

READ MORE

* Healthy distance: Telemedicine bridges gaps between patients and providers

* Looking good: Technology cuts the need for scalpels in cosmetic procedures

* Minds at work: Technology clears a path for mental health providers