The program director of this year's RiverRocks Southeast Wilderness Medicine Conference has taken his medical skills from Haiti to the Himalayas and is one of the nation's leaders in wildlife medicine. One of his most intense moments as a wilderness doctor wasn't in a South American jungle or Central Asian steppe. It was with a group of Baylor students on a school trip.

Chris Moore had a patch over one eye. He had a group leader hobbling around on a crutch made from sticks. He had a sick Baylor student that needed to get off the mountain and another who had just collapsed miles ahead of him.

Over the walkie-talkie, Moore talked another leader through giving the girl an injection, but when the girl's condition deteriorated more, a rescue was becoming a necessity. The girl was short of breath and Moore was short on time as he frantically discussed the girl's condition with group leaders up the slope. But the doctor and the team were also short on batteries. "I said 'Perry are you going to need to be evacuated?' and literally at that moment his line went dead."

The biggest difference between wilderness medicine and conventional medical work is the way doctors are forced to improvise. "We were all trained as doctors to deal with diagnostic equipment and tools of the trade, but you can't carry those in the out of doors," says Moore. And that difference will be the major focus for Moore and scores of other doctors in Chattanooga this month for the RiverRocks Southeast Wilderness Medicine Conference Oct. 4-9.

David Seaberg, dean of the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga, says holding the conference in conjunction with the outdoor festival will make the program more lively. "We feel this conference will help highlight some of the unique aspects of our training program and the city itself," says Seaberg.

Things that should be in your daypack

Duct TapeSignal MirrorsFire-StarterSafety PinsPlastic TiesHead Lamp

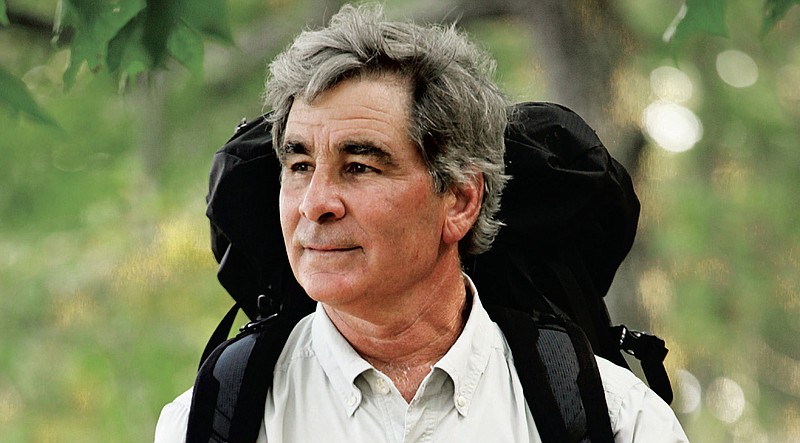

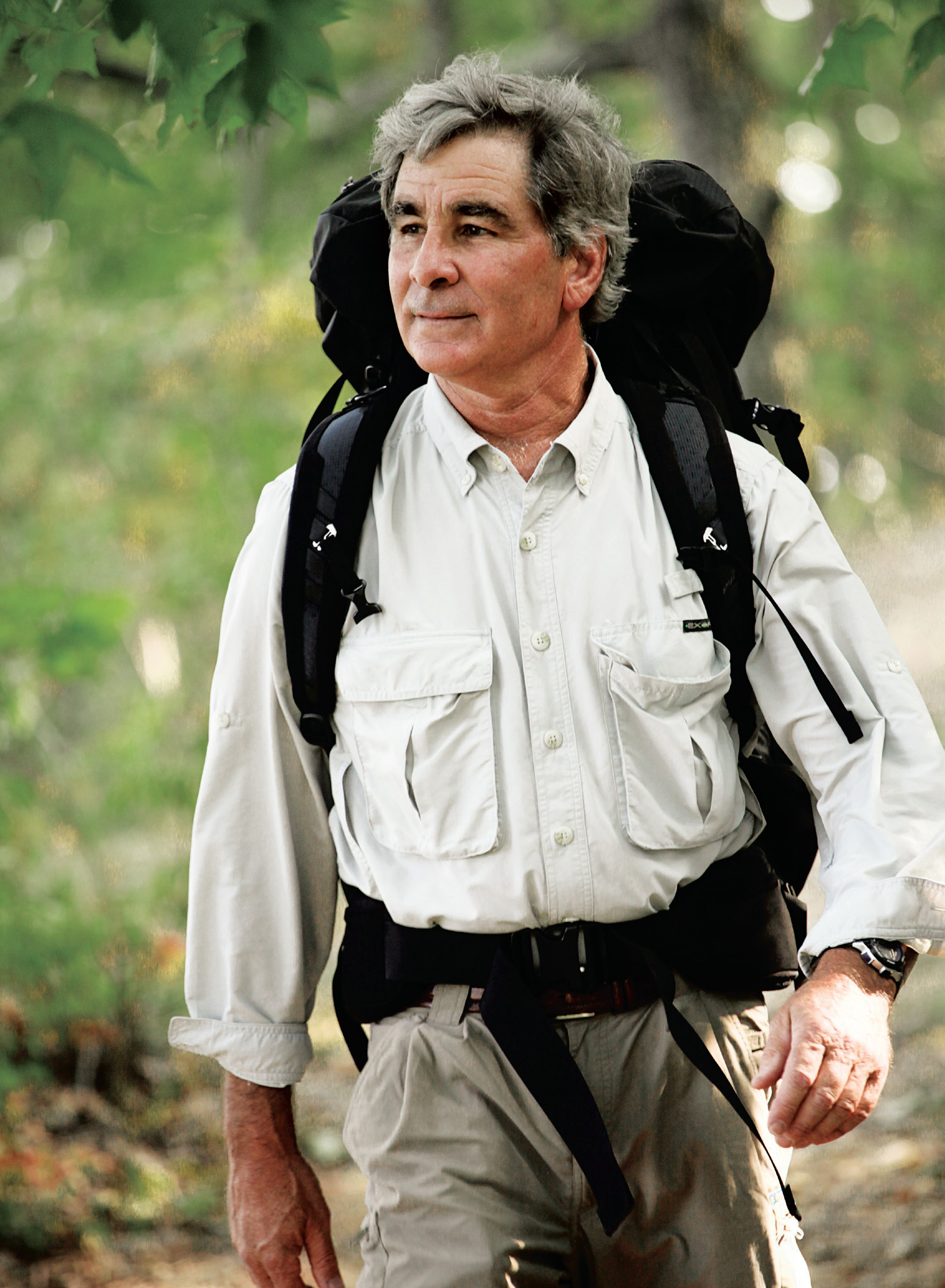

The program director for the event, Moore, 61, has taken his medical skills from Haiti to the Himalayas as one of the nation's leaders in wild medicine. He's been team doctor on the first descent of Tajikistan's Obihingo River for ESPN and on an MTV reality show in the Amazon jungle. He founded Outdoor Chattanooga as well as Baylor's Walkabout Program; worked with disaster relief in Louisiana after Katrina and New York after the Sept. 11 attacks; and was the medical coordinator for the 1996 Olympic Games whitewater event at the Ocoee.

But some of the Baylor School alumnus and Walker County, Ga., resident's most intense moments as a wilderness doctor came not in a South American jungle or a Central Asian steppe, but when he agreed to be team doctor on a Baylor School trip to Colorado.

One summer in the late 1990s, Moore joined a Baylor expedition to climb Huntsman's Ridge, a collection of 11,000-foot peaks near Aspen. On Moore's first morning with the group, the first three hours of their drizzly seven-hour climb breezed by, he recalls. But as lunchtime approached, he heard one of the leaders frantically calling for the doctor - a female soccer player had collapsed.The girl was suffering from what Moore calls "air hunger."

"She's gasping for air; she's wheezing audibly," he recalls. "She was getting worse, not better." He tried an emergency inhaler. No use. Next he grabbed his syringe of epinephrine and jabbed it into the girl's thigh.

To a doctor, epinephrine is a rapid-acting neurohormone that stimulates receptors in the brain to increase a patient's heart rate and relax certain smooth muscles in the throat and intestines. On the ridge, it meant the shot would open the girl's constricted airways allowing her to finally catch her breath.

As the drug took effect, the girl quickly began to improve. But then another concern set in. Even though it was July, rain, altitude and her own perspiration had combined to quickly lower her body temperature.

"Cold can complicate anything," Moore says. As he hurriedly built a fire, an ember popped and hit him in the right eye causing an abrasion on his cornea. "Now I'm treating myself along with her," he explains.

Warmed by the flames and breathing better from the epinephrine, the girl improved quickly. Moore then had to make a diagnosis: did the girl have altitude sickness from the thin air or was something else causing the problem?

Altitude anoxia, as physicians call it, occurs when the lungs can't pull in enough oxygen due to the thin air above 8,000 feet. It can lead to shortness of breath and an inability to walk. Anoxia and high altitude pulmonary edema cause fluid to fill the victim's lungs, causing a headache, lack of appetite and trouble breathing. If it was anoxia, the only way for her to get better was to take her down the mountain.

Moore listened closely to her lungs and decided the wheezing was more of a dry asthmatic wheeze than the choking gasps of someone with anoxia. She also did not experience a headache or loss of appetite. The fact that she had improved without descending strengthened his hypothesis that her problems were not caused by the thin Rocky Mountain air.

After making the call, the doctor and his patient proceeded up the mountain to rejoin the group at a campsite just above 10,000 feet. The next morning, they continued on toward the summit with Moore shadowing the girl. An hour into the hike, she collapsed again. "These are without question some of the top professionals in the world of wilderness medicine," Moore says, glancing over the list of speakers at the conference. One of the doctors is fresh from Everest. Another literally wrote the book on dangerous animals living in coral reefs. One serves as a consultant for NASA. There are more degrees listed on the program than there are lines on a topo map.

Among the lectures, attendees will learn about frostbite, animal attacks, drowning, altitude sickness, hyper- and hypothermia. Workshops will cover cave medicine, water rescue and mountain biking injuries. But getting them all together wasn't easy.

In the early 1990s, Moore explains, all of the wilderness medicine conferences were out West and it took some convincing to draw speakers and attendees to Chattanooga for one of the first Eastern conferences in 1997.

"I kept telling them to come to the Southeast and they kept rolling their eyes like what wilderness is there in the Southeast?" Moore remembers. "People came, people fell in love with Chattanooga."

Moore has revived the idea this year through the UT College of Medicine, and with the RiverRocks festival going on downtown at the same time he says visiting physicians will have the opportunity to hone their skills while also following their passion for adventure sports like paddling and climbing.

"We hope this conference will accentuate the natural beauty of the Chattanooga region and will attract conference participants to take part in the outdoor activities and bring them back for future trips," says UTCOM's Seaberg.

After seeing his patient fall out a second time, Moore decided she needed to get down the mountain. While the group members carried her down the slope, one member, Dawson, sprinted ahead to get a four-wheeler stashed at the group's base-camp cabin. But when Dawson returned, his ankle was badly swollen from a fall during his run. He had fashioned a wooden crutch from branches to help keep his weight off of the ailing joint.

Dr. Moore's 4 rules to avoid disaster

Plan for water. You can survive for many weeks without food, but not many days without water.Always, as in ALWAYS, let others know your itinerary.Cell phones are great, but calling for an evacuation should only be a last resort. Remember, evacuations are reserved for those with life-threatening injuries and you may need to cover the costs of getting you out.Always consider additional clothing. Even in warm weather, rain and wind can change the situation dramatically. Try clothing designed to be lightweight but protective from moisture, sun and cold.

While three-quarters of the group headed back up the mountain to reach the summit, Moore and a female chaperone carried their packs and the patient's gear down to the cabin, arriving after dark. After an uneventful night, Moore and the leaders of the summit group decided to check in with each other on the radio every four hours beginning at 6 a.m. the next day.

Ten o'clock came and went without incident, but at the 2 p.m. check, Perry Key, the summit leader, said a second female soccer player had some minor trouble breathing. As a precaution, Moore used the phone at the cabin to check in with the nearest hospital to see if a helicopter evacuation was possible. Moments later, the radio squawked to life with the panicked message that the second girl had collapsed. Minutes later she was back on her feet, feeling better. After 10 more minutes she hit the ground again gasping for air.

Even riding the four-wheeler part of the way, Moore knew it would take too long for him to reach her. "It is a long way-miles up the mountain on a dirt trail," he says. Mustering his composure, Moore-still wearing his eye patch from the fire injury-used the radio to talk Key through injecting the girl with epinephrine. "I was very confident in Perry," he says. "Not only was he a Wilderness First Responder, but he was a veteran outdoor leader."

As with the first victim, the second girl's condition immediately improved. But it didn't stay that way for long. The girl was still wheezing in the thin air and was much higher on the mountain, making evacuation difficult. Moore and Key discussed their options. Moore believed it was time to call in a helicopter. Right as he asked Key, he heard the summit radio unit go silent as its battery died.

Moore's second patient was now unable to walk, barely able to breathe and isolated without communication in the middle of the Colorado wilderness. It was time to call for a helicopter.

"An evacuation is not an immediate thing," Moore explains. He dialed the hospital in Durango to dispatch the chopper. He and Dawson took off up the slope on the fourwheeler to try and reach the summit team while the first patient and the female chaperone stayed at the cabin in case the hospital or the copter team called. Key said Moore made the right decision.

"He knew it could be life-threatening and he did the right thing to take care of the girl that was in our care," he says. The helicopter couldn't find the summit team and landed near the base cabin. The chaperone and first victim ran to meet it, but the excitement and exertion caused the girl to collapse again.

The focus at base camp then switched back to the first victim, now alone with the chaperone."There was no reaching me or anyone," Moore says. They quickly loaded the gear into a truck at the camp and sped down the bumpy, jarring path to a hospital in Glenwood Springs, Colo. Up the slope, the four-wheeler was roaring up the trail when Moore saw the chopper fly overhead.

When the trail got too rough for the ATV, Moore jumped off and ran to the landing area. He was met by a runner from the summit group, who had to help the flight crew find the rest of the team from the air. Minutes later Moore saw the helicopter take off and disappear into the clouds toward Durango.

Exhausted, Moore and Dawson then headed down the slope to meet the first girl at the hospital, checking on the second patient by phone. He didn't know it at the time, but Moore now believes the girls had a toxic reaction to mold they inhaled. The morning before the doctor arrived, the team had worked on a service project cleaning out an old barn. Unbeknownst to them, they also inhaled mold spores that Moore believes nearly cost the two students their lives.

The ordeal had tested his limits and forced him to improvise. He says the experience made him a better doctor and provided a good lesson about how circumstances can turn quickly in the outdoors, whether it's the Rockies, the other side of Lookout Mountain or the other side of the world. "You don't have to be in the Himalayas for something to go wrong," he says.