Did you know?

Tennessee ranks No. 5 out of the 50 states in terms of where one is most likely to be killed by an animal. (Texas is No. 1.)So, which area wildlife should you beware of? According to numbers compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:Bees, wasps and hornets kill 58 people per year.Dogs kill 28 people per year.Cows kill 20 people per year.Spiders kill 7 people per year.Snakes kill 6 people per year.Bears kill less than one person per year.*Average annual deaths caused by animals in U.S., 2001 to 2013.

Last July, two hikers were on their way to Chattanooga's Audubon Acres when they spotted a black bear alongside Ridgetop Drive, mere minutes from the crowded Hamilton Place mall area.

It was an unsettling idea for many suburbanites - but one that is becoming more mainstream. As certain wildlife populations expand in the Southeast, folks are having to learn to adapt as readily as the wildlife itself.

According to a 2012 statewide public opinion survey conducted by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, 87 percent of residents support having black bears in the state.

"The rub is when those bears start coming around the home," says Dan Gibbs, TWRA wildlife biologist. For example, the survey found that while the majority of respondents supported having bears in the state, only 22 percent supported having bears near their neighborhood and 11 percent supported having bears near their home.

"As bears' proximity increases, our tolerance decreases," Gibbs says, describing this phenomenon as the "cultural carrying capacity." In contrast to biological carrying capacity, which refers to the maximum population size that an environment can sustain given the available food, water and space, cultural carrying capacity is the maximum amount of individuals within a species that humans will tolerate.

Tennesseans must now begin to define these parameters for certain species - including a number of apex predators, animals at the top of their food chain - that are establishing homes near the Scenic City.

Here is a look at some of those species.

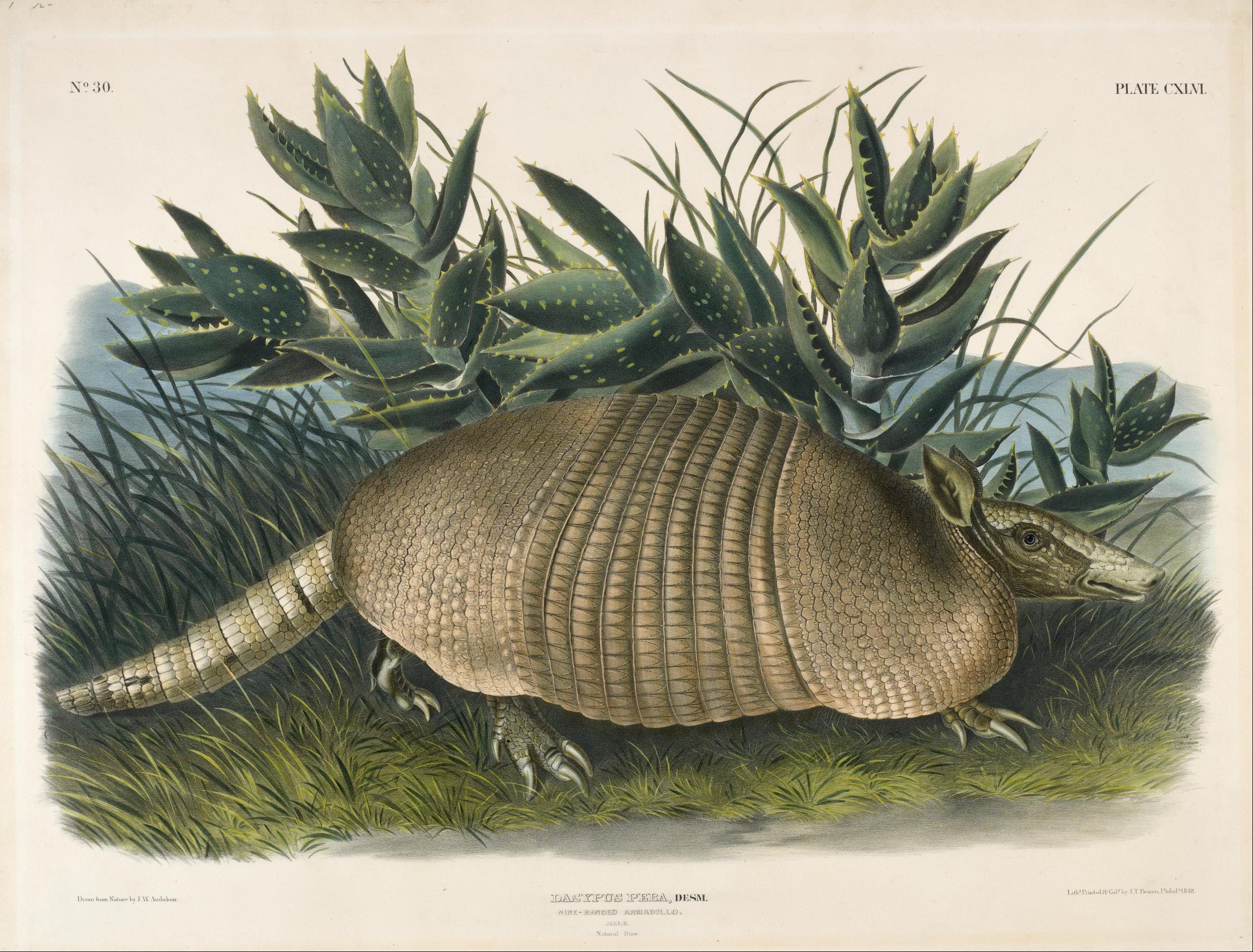

The Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)

The nine-banded armadillo is the only species of armadillo found in the United States. It was first documented by famous naturalist John Audubon in 1854 in southern Texas. Ever since then, the strange mammal has been expanding northeastward, says Dr. Timothy Gaudin, biology professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and co-author of a 2013 report concerning the armadillo's quicker-than-expected expansion.

The species first appeared in Tennessee in 2007 with a confirmed sighting in Sewanee. A couple years later, it arrived in Chattanooga. By now, Gaudin says, it may have made it to Sweetwater, 70 miles northeast of the Scenic City.

One theory on its expanding habitat is global warming. Unlike most mammals, the armadillo has difficulty regulating its body temperature and therefore prefers warmer climates. As regional average temperatures slowly increase, the armadillo's range can expand north.

Good to know:

Armadillos can get a bad rap due to the fact they are the only mammals other than humans known to carry leprosy, a chronic disease that primarily affects the skin and peripheral nervous system (i.e., not relating to the brain or spinal cord) in humans. And it is possible for armadillos to transmit leprosy to humans, though, Gaudin says, it should be noted that there are no documented cases of armadillos carrying the disease in the state.

But, he adds, "You really shouldn't go out of your way to handle an armadillo."

Which is sound advice for all wildlife, really.

How to identify: The armadillo may look reptilian with its scaly armor-like exterior, made of bone and keratin. However, beneath that carapace is fur. The species feeds mostly on insects and prefers to live near streams.

So, how might one know if armadillos are in the area?

First off, they have a habit of digging up lawns in search of macroinvertebrates. "Particularly nice lawns that are well watered," says Gaudin.

But the most common way to identify a local armadillo population is by roadkill sightings. Armadillos tend to get hit a lot. When startled, the animal responds by leaping up to four feet in the air - a good defense when trying to escape a bobcat, but "not terribly effective if trying to escape a Buick," Gaudin explains.

The Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

Once upon a time, black bears abounded throughout North American forests. Then, the European settlers arrived and quickly decimated the population. By 1900, the species was nearly extinct.

In the 1930s, black bears began to make their comeback in the Southeast due to two big reasons: the establishment of the Cherokee National Forest and of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In the 1970s, Tennessee enacted stricter hunting laws, further protecting the population. For example, hunting season was pushed later in the season to prevent the killing of females about to den.

Protection of the species also relies on educating the public. Black bears are not the bloodthirsty carnivores early settlers believed them to be, says Gibbs.

"Bears do a lot better around people than people think," the biologist says. "They're very adaptable and can live within a very small range."

Today, black bears inhabit only 20 percent of their historic range in the Southeast - and that may be all Tennesseans are willing to tolerate. That aforementioned 2012 black bear public opinion survey found that 54 percent of residents felt the bear population size was "about right," where only 23 percent felt it was too low.

How to identify: The average black bear stands 3 feet tall and weighs anywhere between 100 and 500 pounds (though the largest black bear on record, discovered in North Carolina, weighed in at 880 pounds). Without actually spotting the animal, there is a variety of ways to identify bear activity.

First, keep an eye out for small to large stones that have been overturned, something bears do when foraging for insects. Second, look for claw marks on trees. This is how the animals mark their territories. And finally, learn to identify a bear's scat, which is often comprised of seeds, plant material and insect parts.

Staying safe: Since 1900, black bears have killed 67 people across North America. That is an average of less than one person per year. Still, it never hurts to be bear-aware:

Learn to recognize those signs of bear activity.

Carry bear spray.

Hike in groups of three or more.

Never approach a female with cubs.

If approached by a black bear, shout and throw rocks at it.

Be particularly vigilant in August, which is when black bears have increased appetites.

If attacked, fight back!

Never, ever leave food out for bears. As they say, "A fed bear is a dead bear." By leaving out campfire foods or not securing waste, bears begin to acclimate to humans, making them more inclined to approach people. This increases the animal's chance of being euthanized, struck by a vehicle or picked off by poachers. Note: Human food or garbage was present in 38 percent of those 67 fatal bear attacks.

The Boar (Sus scrofa)

Pigs are not native to North America. The animal was first introduced to the Southeastern region by Spanish explorers in the 1500s, when free-range farming practices were common. Inevitably, some of the animals separated from the herd and became the first populations of feral swine.

Then, in the 1900s, Eurasian and Russian wild boars were introduced in North Carolina for big-game hunting. Interbreeding occurred between the wild boar populations and the species flourished.

Now deemed an invasive species in Tennessee, Tom Blount, chief for resource management at Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, calls the wild boar the biggest threat to wildlife in the Southeast.

These pigs proliferate for a trio of reasons, he says: They have no effective predators; sows have two litters per year, ranging from one to 12 piglets; and they eat almost anything.

To try to control the population, Tennessee permits hog hunting from September through February with no bag limits. Recently, Big South Fork partnered with the University of Tennessee for a research project that will capture and radio-collar wild pigs to help determine the animals' distribution. The data will then be provided to hunters to help make harvesting more effective.

How to identify: Due to their diverse ancestry, wild boars range in color from brown, red, black or gray to a combination of those colors. On average they stand between 1.5 and 4 feet tall, and in the Southeast, tend to weigh 150-250 pounds. Their diet includes plants, fungi, insects and even carrion.

Most wild boar populations are not subtle. Their presence can be determined in three big ways.

Rubs are where pigs scratch their bodies against trees, fence posts or telephone poles. The markings are characterized by smoothly rubbed rings around the structure and are spotted between 5-40 inches off the ground.

Wallows are commonly found near rubs. They are shallow, muddy, oval-shaped pools used year-round by pigs to cool down or find relief from biting insects. Wallows can range from 2-7 feet in length and 1-5 feet in width. They might be found in wetlands, ditches, ponds or low spots on well-worn hiking trails.

Rooting is when a hog digs up land to locate food below the soil surface. In Big South Fork, this is threatening rare native Tennessee plants such as the white fringeless orchid, Cumberland sandwort and Cumberland rosemary.

If you spot one:

Be calm and move slowly away.

Never approach a female with young.

Never provoke the animal (i.e., using a flash to photograph it, allowing dogs near it, etc.).

If the wild boar charges, do not run - the animal can outrun you, with the ability to reach speeds of 30 miles per hour. Instead, look for a tree or boulder to climb. If possible, get at least six feet off the ground.

The Cougar (Puma concolor) aka Mountain Lion, aka Panther

Historically, the eastern cougar and the Florida panther are the only two mountain lion subspecies known to exist east of the Mississippi River. At one time, eastern-cougar populations stretched from Maine to southern Georgia. Then, like the black bear, those subspecies were devastated by early settlers. The last record of the eastern cougar was documented in Maine in 1938. In 2011, it was finally declared extinct.

The Florida panther is currently listed as critically endangered.

However, the United States' western population of mountain lions, currently inhabiting 14 western states, is believed to be expanding its range eastward.

In 2015 there were three confirmed cougar sightings in West Tennessee - the first in over 100 years. In Obion and Humphreys County, images of the animals were captured on game cams. In Carroll County, hair and blood samples were collected by a hunter who says he struck one of the animals with a bow and arrow but did not mortally wound it. TWRA analyzed the samples and found they belonged to a female cougar originating from South Dakota.

There have been no confirmed big-cat sightings in Southeast Tennessee. Still, according to TWRA's Gibbs, hundreds of people claim to spot the elusive carnivore every year. Area resident Kristi Dunn is one of those people.*

"We've seen and measured tracks. We've heard [it] screaming - it is a sound like no other. It's not a meow or a howl or a growl.It sounds like a woman screaming."

Dunn says one of her neighbors even snapped a photo of the big cat and mailed a copy to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

"[The USFWS] said it was a bobcat, even though you can see the long tail as plain as I can see my arm," says Dunn. At first, she thought the USFWS was senseless, but then she began wonder if their denial was for the cat's own protection. "Politically, it is a hot potato topic. Typically when a black bear is spotted, it is dead within the week," she says.

As for where the animal came from, Dunn does not believe it emigrated from the west. There are families in her area who have lived there for many generations and one such person, a woman in her 40s, claims to remember cougars being around throughout her childhood.

"I'm thrilled by it," Dunn says of the prospect of having the suspected cougar in their midst. "To me, what it says is that I live in a location that has a healthy ecosystem. We just ignore the mountain lion, she ignores us, and we all get along just fine."

How to identify: Tawny in color, cougars measure an average of 2.5 feet tall and 6-8 feet long from head to tail. They can weigh between 100 and 180 pounds. The eastern cougar, western cougar and Florida panther all look alike. Still, says Gibbs, half of the calls he receives are to report big cats black in color.

Black mountain lions do not exist, he adds. Black jaguars and black leopards exist but are not native to North America. The most common animals mistaken for cougars include small black cows that escape from farms and become lost in woodlands; river otters which have long tails and have been known to cross mountains while scouting new habitat; and black house cats, which, Gibbs says, are sometimes shot by hunters convinced they are cougar cubs.

Staying safe: Like black bears, cougars in North America kill an average of less than one person per year. Since 1970, more than half those fatalities have occurred in British Columbia or California. Also like black bears, the same rules of staying safe apply.

The Coyote (Canis latrans)

Coyotes are extremely adaptable and have been observed shifting their activity from dusk to after dark as they begin to move into urban areas. In 2012, North Chattanooga resident Jeremy Hooper captured game cam footage of a couple of coyotes near his North Shore home. (Contributed photo: Jeremy Hooper)

Coyotes are extremely adaptable and have been observed shifting their activity from dusk to after dark as they begin to move into urban areas. In 2012, North Chattanooga resident Jeremy Hooper captured game cam footage of a couple of coyotes near his North Shore home. (Contributed photo: Jeremy Hooper)Native to the southwestern United States, the coyote began to expand its range eastward in the 1950s, which, not coincidentally, coincided with the building of the first freeway system. Once the new roads and bridges were in place, coyotes moved at will. The wild canine finally arrived in eastern Tennessee in the early 1990s.

"It's a novel predator in the Southeast, and people are just now having to learn to live with it," says Jeremy Hooper, a recent graduate from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga's environmental science program, whose master's thesis investigated the human-coyote relationship in metro Atlanta.

The coyote is remarkably adaptable, changing its behavior as its range expands from rural areas to cities. For instance, coyotes are historically crepuscular, meaning active at dawn and dusk. However, says Hooper, as they begin to move into city parks, golf courses and even large backyards, some populations have been observed shifting their activity to after dark, when they are less likely to encounter humans or traffic - which is the No. 1 cause of death for urban coyotes.

How to identify: The coyote resembles a small to medium-sized German Shepherd, weighing 20-40 pounds on average. There are three main ways to determine if there's a coyote population in the area.

Tracks: Coyote tracks and domestic dog tracks look similar. However, unlike domestic dogs, which tend to travel in a winding pattern, coyotes move in a straight line.

Scat: Rope-like and often filled with hair and bones, coyote scat is used to mark the edges of the animal's territory.

Howl: Howling can also be used to define territory. Or, it might be used to call the family group back together. While coyotes are most likely to howl in the evening, not hearing the animal does not rule out a population. Perhaps not surprisingly, some urban-dwelling coyotes rarely ever howl.

What can you do?

While people living in rural areas seem most concerned with coyote attacks on livestock, Hooper found that within urban areas people are most concerned with pet attacks. But, he continues, "When I followed up with people who reported pet attacks, they didn't actually see the coyote. They just knew coyotes were in the area and then their cat never came home."

Hooper says there are ways to reduce the risk of coyote attacks on pets. For instance, dogs should be kept on leashes during twilight hours; cats should be brought inside overnight. However, the assumption that coyotes are responsible for missing pets will only lead to unnecessary management, he adds.

Besides, there are alternative causes to missing pets. Just last April, an eagle cam in Pennsylvania captured video of a bald eagle feeding a house cat to its eaglets.

"Instead of assuming, look to science. Become knowledgeable about the animals," Hooper implores.

As wildlife patters begin to shift in the Southeast, it provides an opportunity for humans to prove their ability to live alongside even apex predators. "To not live in fear, and to allow these species to exist on the earth - this is a great test for us," he says.

Reporting up the chain

So if there’s something strange in your neighborhood, who you gonna call?For wildlife emergencies (i.e., a black bear family hosting a pool party in your backyard) between 7 a.m. and midnight, call TWRA at 800-831-1174. For wildlife emergencies after midnight, call your local sheriff’s department. For Hamilton County residents, that number is 423-209-7000.If you spot an armadillo, Dr. Timothy Gaudin wants to know about it. Make a note of the date and location, snap a photo if possible, and send an email to Timothy-Gaudin@utc.edu.Government wildlife agencies do not have the manpower to investigate every alleged cougar sighting. However, if you obtain trail cam footage of the animal or find its hair, you should call the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency at 800-332-0900.