What's in a name? When it comes to the trails at Reflection Riding Arboretum & Nature Center, Mark McKnight says the answer is "more than you'd expect."

Long before McKnight became president of the nonprofit nature preserve, Reflection Riding was one of his favorite places to run. Since taking on the position last year and learning about the history tied to the nature center's trails, however, his appreciation for those workout sessions has multiplied.

"It kind of gets you thinking about the people who have been on the trail before you and what they saw," McKnight says.

One of the areas McKnight was most tickled to learn about was Buffalo Field, which sits just south of the nature center's greenhouse.

He had never questioned the meaning of the meadow's fairly mundane title until a visitor told him the field was so named because it was a fenced-in pasture for buffaloes during the 1950s. The guest then showed him old photographs to prove it.

From what McKnight has gathered, the center's founder, John Chambliss, brought the bison onto the property to protect them from being hunted into extinction - a mission in line with the work Reflection Riding is still doing today by raising and breeding red wolves, which are critically endangered.

"It's funny," McKnight muses. "You see these names and you don't even think about them after a certain amount of time. But when you find out what they're named for, they can sometimes be surprising."

Reflection Riding's founder, John Chambliss, named each of the nature center's trails and landmarks himself, often using the surnames of locals who had offered developmental advice or authors who had inspired him. Two of the more centralized trails, however, have names that are a little more personal.

Reflection Riding: Nelson Upslope

This short trail was named after Nelson Irvine, Chambliss' grandson, after the boy coined the word "upslope" to describe the route's upward slope in 1947. The designation pays homage to both Irvine, now a local attorney, and Chambliss' mother, as Nelson was also her maiden name.

Reflection Riding: Susan's Curves

This trail's name perfectly encapsulates its wavy shape while also nodding to Susan Sizer, Chambliss' mother-in-law, whom he admired for her green thumb and who transformed a badly abused lot on the property into a flourishing garden.

Reflection Riding: Sheets Sward

Though not a trail, this grassy area's definitely got a story to tell. The plain was named after Jim Sheets, a young flying cadet whom Chambliss' daughter Margaret met during an outing back in 1942. When Margaret inquired about the roll of parchment Sheets had with him, he unrolled it to reveal a watercolor he had painted titled "Farm From Sunset Rock." Recognizing the farm immediately, Margaret told Sheets it was her father's field, and he gifted her the artwork, much to her father's delight. "It rather inspired me as he, with the proper license of the landscape painter, had 'improved' some of the ugly aspects that were apparent then," the late Chambliss wrote in an article published by the Chattanooga News-Free Press in 1970.

Stringer's Ridge: Double J

Most squinting at a map of this trail might assume its name is merely derived from the dual half-loops that make up the path, both of which resemble upside-down "J"s. But in reality, the shapely trail is also named after Jim Johnson, the Chattanooga resident and avid cyclist whose generosity helped make the Stringer's Ridge trail system the local favorite it is today.

In 2011, back when the ridge was no more than a haphazard collection of overgrown pathways, Johnson donated $50,000 to the Trust for Public Land to help build trails, enabling the organization to leverage more dollars to begin the work.

Touched by Johnson's generosity, planners suggested the trust name one of the newly developed trails after him. When they were reminded that trails aren't traditionally named after people who are still alive, the group found a loophole, choosing to characterize the route by its dual J's - which just so happened to mimic Johnson's initials.

"That way, it's sort of named after you, but you don't have to be dead," they told Johnson, who was president of the Chattanooga Bike Club at the time.

Today, Johnson is greeted with the occasional "Hey, Double J!" while running or biking on the trail, though he says seeing locals enjoy the urban forest due, in part, to his contributions and two years of volunteer work is his real reward.

"It's gratifying to see the outcome," Johnson says. "Watching people out riding, running and hiking, especially families, warms my heart."

Still, he adds, he's already discovered one humorous downside of having a trail dedicated to him. He recalls watching two mountain bikers huff and puff their way up a tough section of the namesake trail on a particularly hot day this summer.

"I heard one of them shout, 'I hate Double J!'" he laughs. "For a moment, I had to remind myself she was talking about the trail, not me."

Stringer's Ridge: Negley's KnollThis gradual climb, which loops to the highest point on Stringer's Ridge, was named after James Negley, the Union general who fired the first shell on Chattanooga during the Civil War on June 7, 1862, kick-starting the minor artillery exchange now known as the First Battle of Chattanooga.

Stringer's Ridge: Alta Vista

Before it became the name of this short Stringer's Ridge trail, Alta Vista was the name of a nearby farm owned by one J.E. Sawyer. Sitting on what is now Memorial Drive, the farm served as a secret camp for Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and his troops after they crossed the Tennessee River near Brown's Ferry during the Civil War. During the mid-1980s, the farm was converted into White Oak Cemetery, now called Chattanooga Memorial Park.

South Cumberland State Park: Fiery Gizzard

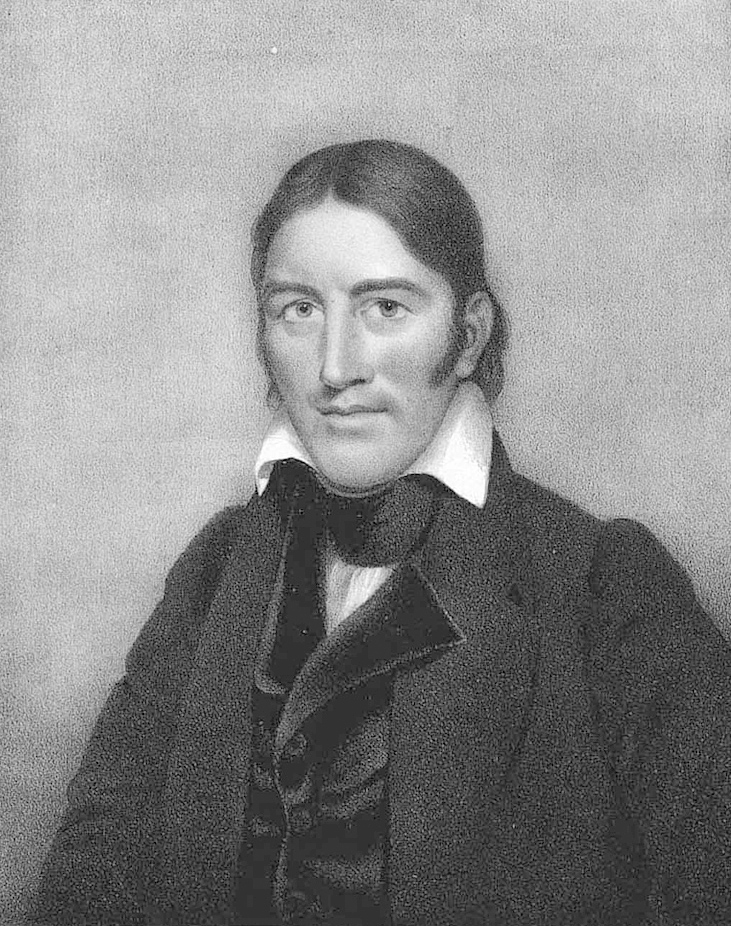

Legend has it that this 13-mile trail in South Cumberland State Park was named by the one and only Davy Crockett, though the story is quick to change depending on the storyteller.

According to the version some volunteers with the Friends of South Cumberland like to tell, the 19th-century folk hero conceived the strange name around 1813, after an unfruitful hunting trip in the gorge left him tired and hungry. While making his way home, they say, Crockett came across a small, creekside cabin, whose inhabitants were sitting around a fire topped with a steaming kettle.

Lured in by the aroma of boiling turkey, Crockett did not hesitate when the settlers invited him to partake in their meal. Rushing over, he fished a piece of turkey out of the kettle with his hunting knife and plopped it into his mouth - only to spit it into the gorge a moment later when the scalding meat singed his tongue. Yelping in pain, Crockett turned to the settlers and said, "Damn, that was a fiery gizzard!"But that isn't the only legend of how the name came to be.

Another folktale familiar to park volunteers tells of a peace conference between the Cherokee and early settlers, during which the Native Americans arrived to find the Europeans in the midst of a raucous celebration, having arrived at the meeting place three days prior.

According to the story, the Indians stood, arms crossed, their arrival ignored and subsequent attempts to communicate drowned out by the feasting and laughing, as well as by the shooting competition taking place on-site. Frustrated, the chief marched over to a contestant just as he was raising his rifle, snatched the weapon away and smashed it against a nearby tree.

Further irked by the resulting cheers from the drunken crowd, the chief turned to the wild turkey intended to serve as a prize for the match's winner. He seized the struggling bird by its neck, held it above his head, took out his hunting knife and sliced out its innards. Many of the frightened settlers sped for cover as the chief strode over to the fire and dashed the remains into the flames. As the sparks and feathers settled among the now-silent campground, the Indians could be seen smiling over the fiery gizzard, storytellers say. The smirking chief then stepped forward and said, "Now that we have your attention, we can talk."

Lookout Mountain: Moonshine Trails

Previously called the Gerber Branch area, this recently redeveloped site along the Chattanooga Connector Trail on Lookout Mountain was originally named after local distiller Fred Gerber, who illegally produced his corn liquor there during Prohibition. To this day, visitors exploring the area can find piles of bottles that were to be filled with whiskey near the trails. In light of the discovery, the three trails added to the area last year were branded with colloquial names for whiskey and moonshine: White Lightning, Firewater, and Bathtub Gin.

Audubon Acres: Dragging Canoe

Those who know their history will recognize the significance of this Audubon Acres trail, named after Native American War Chief Dragging Canoe, considered the greatest Cherokee military leader by many historians.

Born in the 1730s, Dragging Canoe earned his name at an early age by demonstrating his unyielding desire to fight alongside his elders. As the story goes, the young Indian begged his father, Attakullakulla, to let him join a war party that was moving against the neighboring Shawnee tribe. Believing the boy to be too young for battle, Attakullakulla told his son he could accompany the warriors - but only if he could carry his own canoe, a task he knew the child would be unable to do.

As expected, the boat was too heavy for the boy, but his determination never wavered. Though he couldn't lift the craft, he managed to drag it along the way, garnering the warriors' respect and encouragement, as well as the name that would one day grace history books.

His perseverance can easily serve as motivation for Chattanoogans training on his namesake trail today.

"It's kind of your quintessential underdog story," says Kyle Simpson, executive director of Audubon Acres. "It's about pushing through with sheer determination."

During his lifetime, Dragging Canoe would gain recognition for his opposition of the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775, which led Cherokees to leave their land - which encompassed all of what is now Middle Tennessee and the state of Kentucky - in exchange for guns, ammunition, beads and blankets. He is also known for continuing the fight against land-hungry settlers throughout the years that followed, strategically retreating and establishing towns in what is now Chattanooga with his Cherokee supporters.

Though there is little evidence that Dragging Canoe lived in the vicinity of the trail, Simpson says he believes Robert Sparks Walker, Audubon Acres' founder and a noted Cherokee historian, named the path after Dragging Canoe because it lies adjacent to the Ford of Youth, a shallow crossing in the creek whose worn terrain suggests it has been in use for hundreds of years.

"If Dragging Canoe was active on South Chickamauga Creek, it's extremely likely he would have used that at some point," Simpson says.