EVEREMAN EVENTS• Friday, April 18. 6 p.m. The Farmer's Daughter 1211 Hixson Pike, Jay Wiggins will give a presentation on the Evereman project.• Saturday, April 19. Noon-4 p.m. Artifact, 1080 Duncan Ave., will host an Evereman production party. All are welcome; donations are appreciated; 4-6 p.m., art will be dispersed for a city-wide scavenger hunt; 7 p.m.-midnight., 201 W. Main St. Evereman celebration complete with a sculpture burn, live music and food.ONLINEFollow @Evereman on Instagram and Twitter to stay informed and participate. Tag these accounts and #FA4U (Free Art 4 U) when posting pieces that are found.

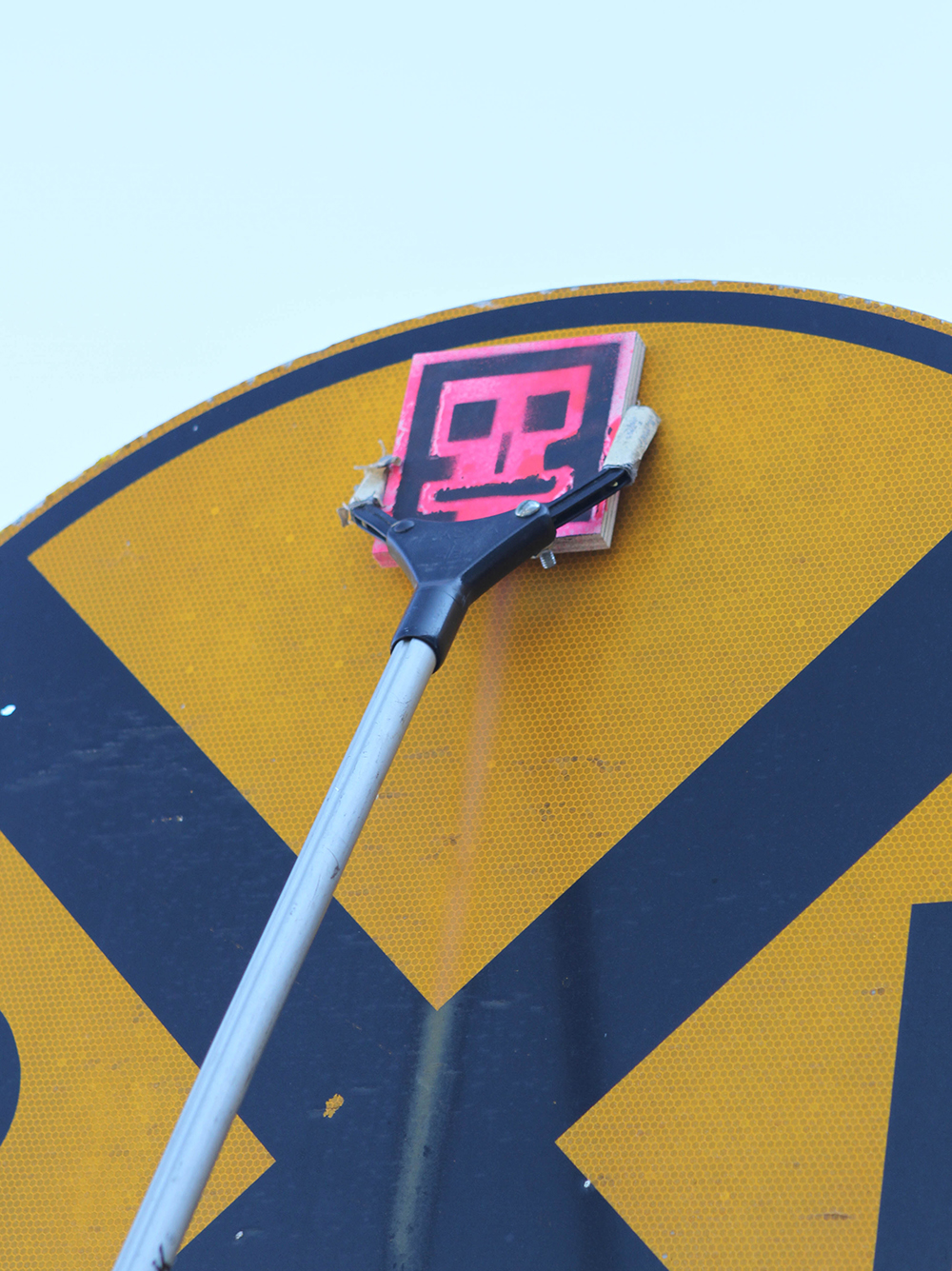

Atlanta street artist Jay Wiggins hangs an Evereman art piece from an empty sign post on Main Street in Chattanooga. Wiggins, who is regarded as the grandfather of the Atlanta free art movement, came here to decorate neighborhoods with artwork that community members can collect and eventually redistribute.

Atlanta street artist Jay Wiggins hangs an Evereman art piece from an empty sign post on Main Street in Chattanooga. Wiggins, who is regarded as the grandfather of the Atlanta free art movement, came here to decorate neighborhoods with artwork that community members can collect and eventually redistribute.Most people driving by the little block faces hanging here and there from Main Street to North Shore probably had no idea where they came from.

The pieces were placed at random, often just out of reach on street posts or in the corners of buildings. They were small squares, each colored differently with the same robotic expression staring down to the sidewalk. It's not clear why they were there; they seemed out of place. But to the man who placed them, they are art.

Jay Wiggins, 55, is better known by the name he has given to these stenciled faces - Evereman - a nod to his intent that the work be for everyone. With his own face framed by a long, white beard, reflective aviator sunglasses and black knit cap, Wiggins looks exactly how he's described: The grandfather of the Atlanta free art movement. And he came to Chattanooga on Feb. 15 to spread his art and the philosophy behind it to the Scenic City and its art community.

"We're all in this together, and let's look out for one another," Wiggins said. "That's the crux of it for me ... I think we could do a lot better if we had more empathy and worked together."

Free art is a straightforward, international concept that has shown up in cities from London to New York. Create and distribute, collect and redistribute. Artists decorate their neighborhoods, often posting pictures on social media of where they've put their work, helping followers find the pieces. Collectors keep what they find, then put the collected pieces back on the streets when their trove grows too big. Residents explore their community, hunting for new pieces. Strangers share with one another.

"I don't like to call my art 'free,'" Wiggins says. "I like to think of it more as a gift. There's power in giving."

Wiggins' art has always been in the streets. Art was a refuge for him in childhood and continued to be one when he migrated from a small town in North Carolina to the nearest big city - Atlanta. Once there, Wiggins stenciled poetry on sidewalks in the neighborhoods of Midtown and Little Five Points. He manipulated billboards, attaching a long spear to pierce the chest of the pictured model in a piece that was later featured in the book "Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art." This was in the early '80s before "street art" was a term anyone used, including Wiggins himself. He just wanted his work in front of more eyes.

"What I'm doing now is about trying to bring people together, not trying to raise feathers," Wiggins said. "I'm much more aware of other people's property."

Evereman began as a pet project more than 10 years ago with scraps from Wiggins' furniture shop and the assistance of his son, Ned. The two painted little faces on leftover wood and glued them around town to brighten neighborhood blight - one on a concrete wall here, one on an abandoned signpost there. Wiggins started seeing strangers' photographs of the Evereman, which he liked.

"People were enjoying finding them," he says.

Then he started noticing the glue spots left around town when his art was taken by admirers, which he didn't like.

"I thought I would just make them easier to take and make them leave no trace," Wiggins said.

Evereman is now hung by magnets, hooks or gravity, an approach Wiggins calls "friendly art." He estimates he's dropped more than 30,000 pieces at this point, funded primarily from his own pocket, cushioned by an occasional grant or commissioned piece.

Wiggins' February visit to Chattanooga was his third art drop for the city, and he brought Atlanta street artists Sad Stove and Job to spread their work - Sad Stove makes tiny magnetic stoves with frowny faces and Job paints colorful mask-wearing Mexican wrestlers known as luchadors.

Street artists like the mystique of being nameless and faceless, saying it lets their work take on a life of its own. But free art also has become so huge in Atlanta that some artists actually have stalkers who hang around their houses to get a jump start on collecting. Anonymity helps there, too.

Wiggins always drops art during the day, but he walks calmly and with purpose, so people rarely ask why he's using a grabber pole to hoist squares up on street signs or leaving blocks on walls.

"It really has been something of a social experiment," Wiggins says. "The bigger work for me has been seeing what people do besides finding it for themselves."

Sometimes Wiggins posts a photo of the piece on Twitter and Instagram, sometimes he just walks away, but always he's looking for the reaction - if people notice his art, if they take it, if they smile. On this day, he points out a small Evereman square to a little girl and encourages her to grab it from the fence.

"Once you find it and you're in a crowded place, you just get it. You want to jump up and down," says Atlanta street artist Blockhead, an Atlanta street artist, recalling the first time he found Evereman. He doesn't want his name used because of potential stalkers.

A desire to recreate that feeling for others now drives Blockhead's work, carved figurines with clunky cubes for heads that often feature one painted detail, like a tie or a mustache. He and Wiggins have now collaborated on more than 80 pieces - Blockhead figures with Evereman stencils for faces.

"Once you put something out, people get excited about it," Blockhead said. "They leave their homes, they race to get it, they love it."

Fenix, another street artist mentored by Wiggins, started painting and putting out her bright, cartoonish phoenixes for similar reasons.

"I had seen how street art was improving my neighborhood by championing a lot of local pride, and I wanted to do something similar," Fenix said.

Most free art is intentionally placed in areas of town that are less trafficked, require walking and feature small businesses; the idea is to encourage residents to explore the city and interact with their community.

"I want people to have a memory and an experience associated with the hunt," Fenix said. "Not everyone finds a piece, but I hope that everyone comes away with a fun thing that they did that day."

On any given day in Atlanta, there are between 50 and 80 artists posting free art around the city. There's a hashtag for those who drop on Friday, #FAFATL. It's a full-fledged community with organized events and collaborations.

For his part, Wiggins keeps new and seasoned artists invigorated by hosting production parties where everyone, regardless of skill level, is invited to help make Evereman pieces in assembly-line fashion, step by step.

"You're just in his house and you're working on his art, engaging with other people," Blockhead says. "It's fostered a community of people who work together, who help each other with their art."

It's all part of Wiggins' mantra: Cooperation yields better results than competition.

That sentiment applies to those collecting free art, too. Wiggins asks that, if a person takes more than a couple, they do so with the idea of putting them back out for others. Bigger pieces are intended to stay out for everyone. Hopefully.

"It's got its own life on the streets," Blockhead said. "That's something he really influenced me in ... once you put something out, just letting it go, whether it stays on the street or go to somebody's home."

It's part of what makes free art so special, Wiggins says.

"It's grown very organically," he said. "It's incredible to me that the symbiosis between the artist and the participant has steered the project."

Wiggins hopes that path will take him on a tour of mid-sized Southern cities this year, but between an already-prominent public art scene and recent downtown revitalization, he wanted Chattanooga to be the first stop. Besides exploring these areas with more art drops, Wiggins is planning an Evereman production party in Chattanooga for April.

Less than a week after his visit, nearly all the Evereman pieces in Chattanooga were gone. One still hung above Velo Coffee Roasters. Owner Andrew Gage had left it up. He wanted it there.

"I feel like it's almost like the artist chose us," Gage says. "It made me feel special, it's like a little gift."

Contact Maura Friedman at mfriedman@times freepress.com or 423-757-6304.