The barge has been an iconic part of Riverbend from the start. Over the years, it has undergone serious wind damage, leading to a new cover, and it has been outfitted with more modern and better audio, lighting and video equipment. Pictured in this undated file photo are some of the many staff and volunteers who have helped stage Riverbend over the years.

The barge has been an iconic part of Riverbend from the start. Over the years, it has undergone serious wind damage, leading to a new cover, and it has been outfitted with more modern and better audio, lighting and video equipment. Pictured in this undated file photo are some of the many staff and volunteers who have helped stage Riverbend over the years.When Walker Breland thinks back to the very first Riverbend Festival in August 1982, he remembers first going to people like Scotty Probasco, president at American National Bank, and Carey Hanlin, CEO at Provident Insurance, "and asking for a loan that would never be paid back."

"Carey just sat back and laughed, but then he turned around and wrote a check for $25,000," says Breland, professor emeritus from the Music Department at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Breland also recalls riding up and down the Tennessee River in a boat with singer/songwriter Roberta Flack following her performance on the fifth night of the then six-night festival. Flack, who earned three No. 1 hits and four Grammys between 1972 and 1974, was the biggest name at the inaugural Riverbend.

"We sailed up and down that river until 3:30 in the morning," he says. "I was at church the next morning at 8:30."

It was a moment that gave him the inspiration to make Riverbend work in the long haul.

As the first president of the board of directors for the first Riverbend, Breland was there almost from the beginning. But the details of where, when and how the long-running festival actually got started depends on whom you ask. Each has their own memories and interpretations of the series of events that led to the creation of an event heading into its 33rd year.

For Sid Hetzler, a former reporter, college professor and local business man, it's a pretty straight line from September 1980, when he visited Charleston, S.C., and attended the Spoleto Charleston Festival, until the first Riverbend. Having a Spoleto in Chattanooga was his ultimate goal, and he says his trip to Charleston is the true moment of conception for Riverbend.

"It's complicated, of course, but I did live through it," he says in a recent email. "Probably the story of the blind men describing an elephant explains the reality, but there is a clear timeline."

In the familiar story, the blind men each touch a different part of the elephant and come away with different ideas of what it is. One touching the leg decides it's a tree; one at the trunk thinks it's a snake, one at the ears thinks it's a fan.

For others, the Riverbend line is not quite as straight. In fact, it's not even a single line, but a series of separate lines that eventually merged into one. There is little doubt that Hetzler, with financial help from the Lyndhurst Foundation, was the driving force behind the first Riverbend Festival, however.

A few other things are certain, as well. The first Riverbend was held at several downtown locations, including a chamber music concert at the Tivoli Theatre, a hot-air balloon launched from Vine Street and carrying a brass trio, and a children's film festival at the old Kirkman High School. Some events were ticketed, but most were free. The now-familiar pins did not come into play until the next year. And the idea for having it take place primarily at Ross's Landing also came later.

Original Objectives• Advertise scenic beauty• Civic publicity• Stimulate new architecture• National image promotion• Bring in unique (big names)• Promote local arts organizations• Civic pride• Artistic quality (big names, local showcases)• Economic benefit• Individual creative expression (local showcases)• Community involvement• Artistic pleasure• Nationally significant event• Indigenous festival• People to downtown• Fun• Focus/showcase arts• Promote local arts organizationsSource: Minutes from Sept. 19, 1981 board meeting

Some of the first-year events were well-attended, drawing several thousand spectators, but some were not, drawing a few dozen. Some planned events were cancelled because of lack of fan support.

In some ways, figuring out who started Riverbend is like trying to definitively pinpoint who invented rock 'n' roll; you can name dozens of artists that could claim part of the title, yet each of those had their own influences in the past.

Still, it can be argued that the first Riverbend set the stage for the city's renaissance, which included the opening of the Tennessee Aquarium in 1992 and the 21st Century Waterfront project, which transformed Ross's Landing into a year-round destination for locals and tourists in 2005.

And when looking at how it all came together, you also see the inner workings of the city's artistic, civic and business leaders, getting a glimpse at the creation of the "Chattanooga Way" -- the spirit of cooperation that current civic leaders still like to reference.

But the birth of Riverbend had plenty of labor pains.

First Roots

After returning from his trip to Spoleto, Hetzler hosted a brainstorming session at his house and eventually chaired a group that would later hire Bruce Storey, who died earlier this month, and his newly formed events-producing company, Variety Services, to run the new festival.

The line takes a turn from there, however, when the festival-in-waiting almost immediately deviated away from Hetzler's original idea of a highly artistic event spread over several weeks and featuring chamber and symphonic music, films and theater performances at various locations all over the city, a la Spoleto. The new idea put more emphasis on music and vendors on the river.

The Bessie Smith Strut, originally called the Bessie Smith Jazz Strut, on Ninth Street, now M.L. King Boulevard, was a hit from the start with people who enjoyed the mix of cultures, the blues, barbecue and beer. This photo is taken from the railroad trellis on MLK looking back toward the Chubb Life building.

The Bessie Smith Strut, originally called the Bessie Smith Jazz Strut, on Ninth Street, now M.L. King Boulevard, was a hit from the start with people who enjoyed the mix of cultures, the blues, barbecue and beer. This photo is taken from the railroad trellis on MLK looking back toward the Chubb Life building.Hetzler and Richard Brewer, who was partners with Storey in Variety Services, insist that an event called Five Nights in Chattanooga, which Variety produced in 1981 with a $150,000 grant from the Lyndhurst Foundation, had nothing to do with Riverbend. Technically, they are correct.

Five Nights was held at the intersection of what is now M.L. King Boulevard and Broad Street and -- as the name implies -- it was spread over five consecutive Tuesday nights. Headliners at the free concerts were B.B King, Bill Monroe, Don McLean, Sarah Vaughan and Hank Williams Jr.

The plan came out of a recommendation by a consultant from New York who was hired to find a way to bring people to a downtown that, at the time, rolled up the sidewalks after 6 p.m. Five Nights lost money, but proved a point to some people, especially those concerned by deteriorating race relations in the city.

"Five Nights was a test to see if people with different backgrounds would come downtown. It showed that they would," says Mickey Robbins, an original member of the committee that Hetzler chaired. That committee also included attorney Nelson Irvine, who served as secretary, and UTC professor Fred Behringer, who served as treasurer.

"We were looking at where the city was," Robbins recalls. "There was a need for racial healing, an economic boost and several other factors. It [Five Nights] was the precursor to what happened afterwards."

At the time of Five Nights, Robbins was director of the Chattanooga Arts Council, which merged in 1982 with Allied Arts of Greater Chattanooga, now called ArtsBuild. Several groups in town were searching for ways to move the city forward both artistically and from a civic standpoint, he says, and, in many ways, Riverbend became that vehicle, providing an opportunity for diverging groups with equally divergent agendas to work together for the greater goal.

"There was a definite progression there," says Robbins.

Attorney Hugh Moore, who joined the Riverbend board in 1983, called the music festival's creation "an organic progression."

Also in 1981, after Five Nights, Lyndhurst provided a $26,000 grant that allowed a group of leaders, including Hetzler and Mayor Pat Rose, to attend Spoleto and fund some research seminars in Chattanooga that explored the idea of establishing a local festival. At the time, festivals were a fairly new concept, so essentially the Chattanooga committee was creating something unusual.

After doing their research, the committee submitted a document to Lyndhurst titled "Proposal for Funding to Establish a Chattanooga Festival." Though it technically was centered on a fine-arts festival similar to Spoleto, it also provided a blueprint for Riverbend.

After Riverbend began, other cities Southeastern like Birmingham (City Stages) and Atlanta (Music at Midtown) created their own downtown music festivals. Nashville's Summer Lights began the same year as Riverbend. The victims of excessive financial losses, those three disappeared (although Music at Midtown resurrected itself in 2011). But even in their heyday of the 1990s and early 2000s, most of the music festivals that arose in other cities were three- or four-day events, unlike Riverbend's week-or-more schedule.

Growing pains

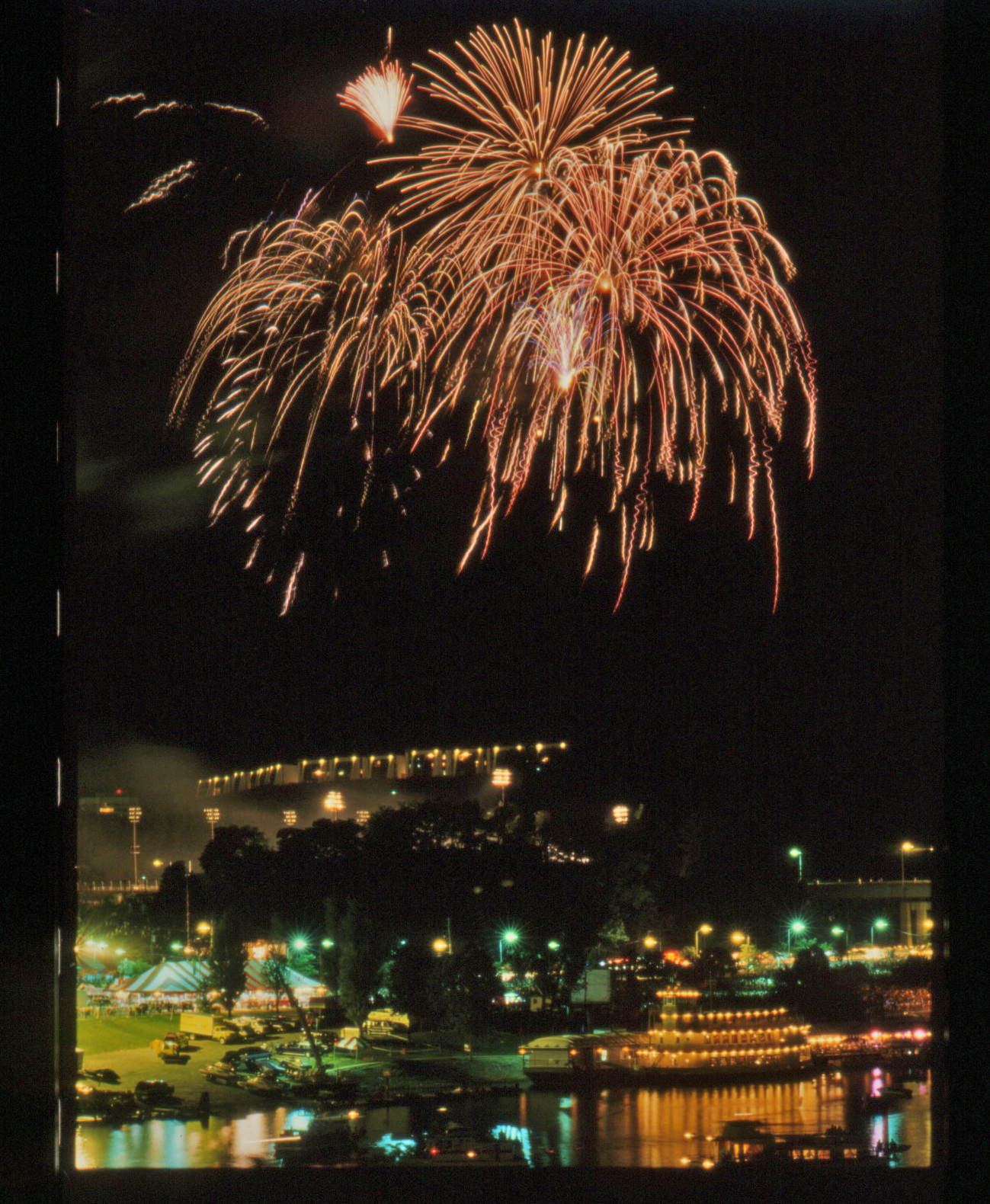

When Riverbend began, it was not the same Ross's Landing that's now part of the multi-million dollar 21st Century Waterfront. In fact, very little of what exists today near that part of the river is the same. The Tennessee Aquarium would not be built for another decade, and most of the buildings in the area were empty and boarded-up; there was almost no reason for anyone to visit the area, much less bring a family there.

Storey is largely credited with pushing Riverbend in the direction it eventually went, including the type of musical programming still going today. Breland says it was Storey who personally asked him to be the festival's first president.

"Part of Bruce's genius was getting Walker involved," says Robbins.

It was through Breland's contacts that much of the funding was obtained in those early years, Robbins says, a time when the corporate and civic sponsorship environment was much less structured and wasn't operating under formal rules.

"People gave out of a sense of civic pride," Robbins says.

Breland says "it is a miracle the thing got started and has continued."

To provide seed money for the larger festival, Lyndhurst provided $150,000 for three concerts at Engel Stadium, one each in May, June and July of 1982 and headlined by Rick Springfield, The Commodores and The Beach Boys. None of the shows made money, and even had some drama of their own.

"On the day of the show, the Commodores' manager said they would have to be paid in cash," Breland says, something that was not readily on hand.

When the band threatened to leave town without playing, Rody Davenport, whose family owned all the Krystal restaurants in Chattanooga, "went to every Krystal in town and cleaned out every till of cash to pay them," Breland says with a laugh.

Storey had also been involved in the Arts & Education Council which, in the early 1980s, was producing dance programs in town as well as bringing in guest speakers and authors. The AEC has since become the Southern Lit Alliance and still produces the Celebration of Southern Literature, a weekend event hosting of Southern writers.

Storey also played a role in starting the Dorothy Patten Fine Arts Series, which showcases performing arts such as music, spoken word and theater. So when talk began of putting together an arts festival to promote the city, many forces fell into place under his leadership.

While the list of original goals for the as-yet-nebulous festival included things like "economic benefit," "people to downtown," "civic publicity," "civic pride" and "artistic quality," which the committee defined as featuring big names and local showcases in any creative area, the committee was looking for an event to showcase fine arts at various locations around town.

During those early discussions, however, it was decided that Chattanooga was not Charleston and the festival would not be another Spoleto. Instead, it should focus on what was already here, Breland says.

"We had chamber music and choral music and orchestral music," he says, "but we also had mountain music. There was a nasty attitude toward mountain music, but this is mountain, or fiddle music, territory."

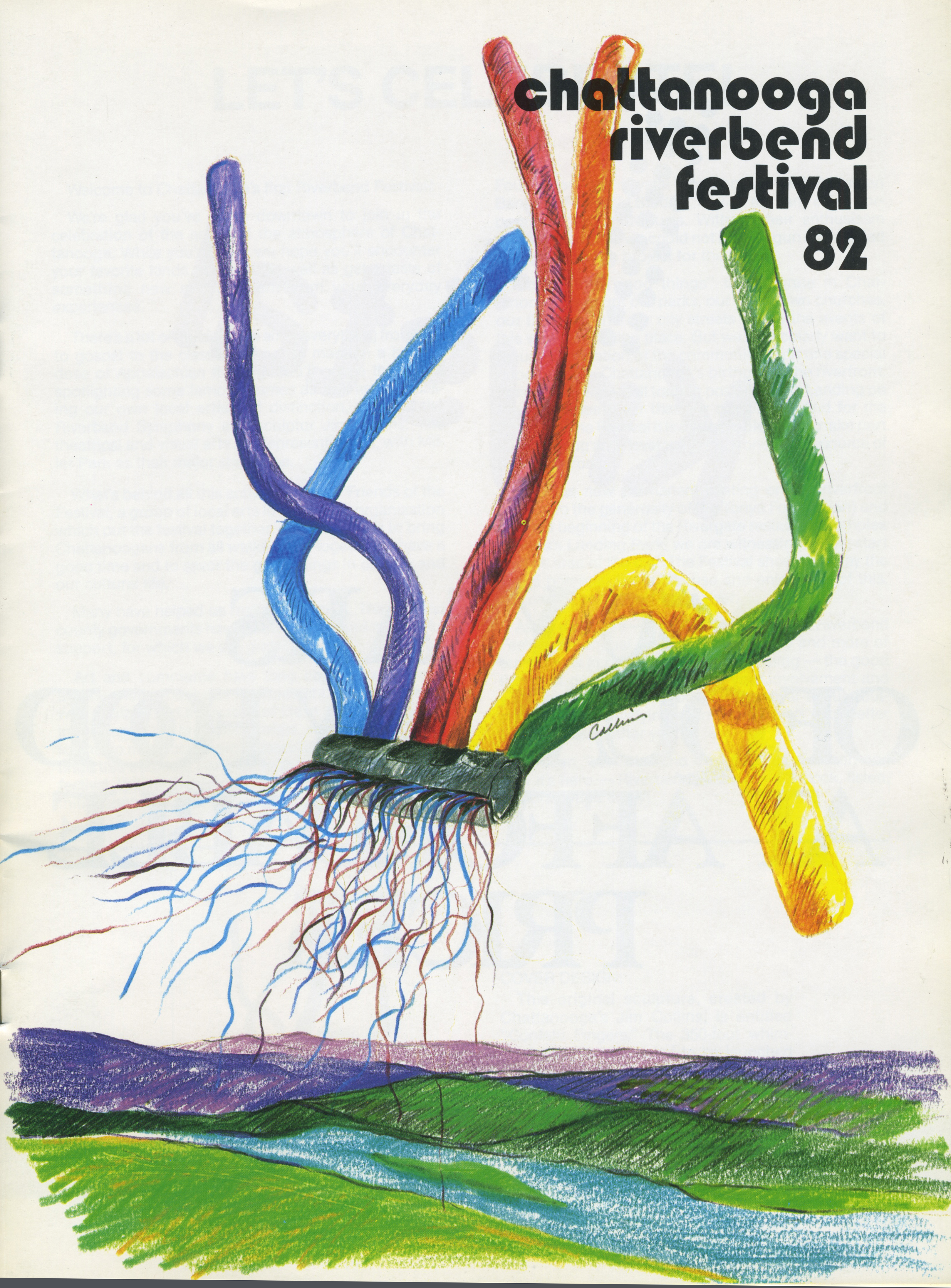

The first festival, which was free and ran from Tuesday to Sunday, Aug. 25-29, included a patron's cruise on the Southern Belle riverboat, organ recitals at two downtown churches and a fiddle competition. The Chattanooga-Hamilton County Bicentennial Library hosted events for kids, and a children's film festival was held at the old Kirkman High School. Downtown businesses such as the Brass Register, the Gazebo, Dr. Sage's and Scrappy's -- all now closed -- were listed on festival programs as places to go after the music at Ross's Landing.

Operating with only one stage, located where the Coca-Cola Stage is now, performers included Flack, John Hartford, who performed on Saturday and emceed the International Fiddler's Championship Finals on Sunday. Several local acts, including Overland and the Chattanooga Choo Choo Barbershop Chorus took the stage. There was a Downtown Arts Festival at Miller Park.

In subsequent early years, the festival included boat/ski/jet ski races on the river during the day. The festival eventually added three more nights so vendors could make money, according to Robbins.

At first, the city kept Riverfront Parkway open to traffic, using a fence to separate the road from the festival area. That changed after the Pointer Sister show in 1985. Crowds were so large for the concert, the fence was removed for safety reasons and the entire Riverbend site has been closed to vehicle traffic since.

"(Riverbend) succeeded by changing," Moore says. "I'm not sure anyone would have imagined that it would still be going, but the board has held very true to those original goals, and part of that is the local element and bringing people together.

"You just have to walk around down there and see people from Whitwell and Signal Mountain and Lookout Mountain and Alton Park."

Contact Barry Courter at bcourter@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6354.