This Memorial Day, we honor our fellow Americans who willingly and courageously mounted up and deployed to faraway lands and gave their lives for our continued freedom. Before you pop one open or flip a burger, before your backyard festivities begin, put your hand over your heart, bow your head and give thanks to heaven for our courageous, fallen service men and women, God's favorite angels.

***

When you get hit, two things happen. You hear the crack and feel the thud. In my case, shrapnel, white-hot and razor-sharp. At first, it just stings. Then a fire, from within, ignites. It's hard not to scream. It just keeps burning.

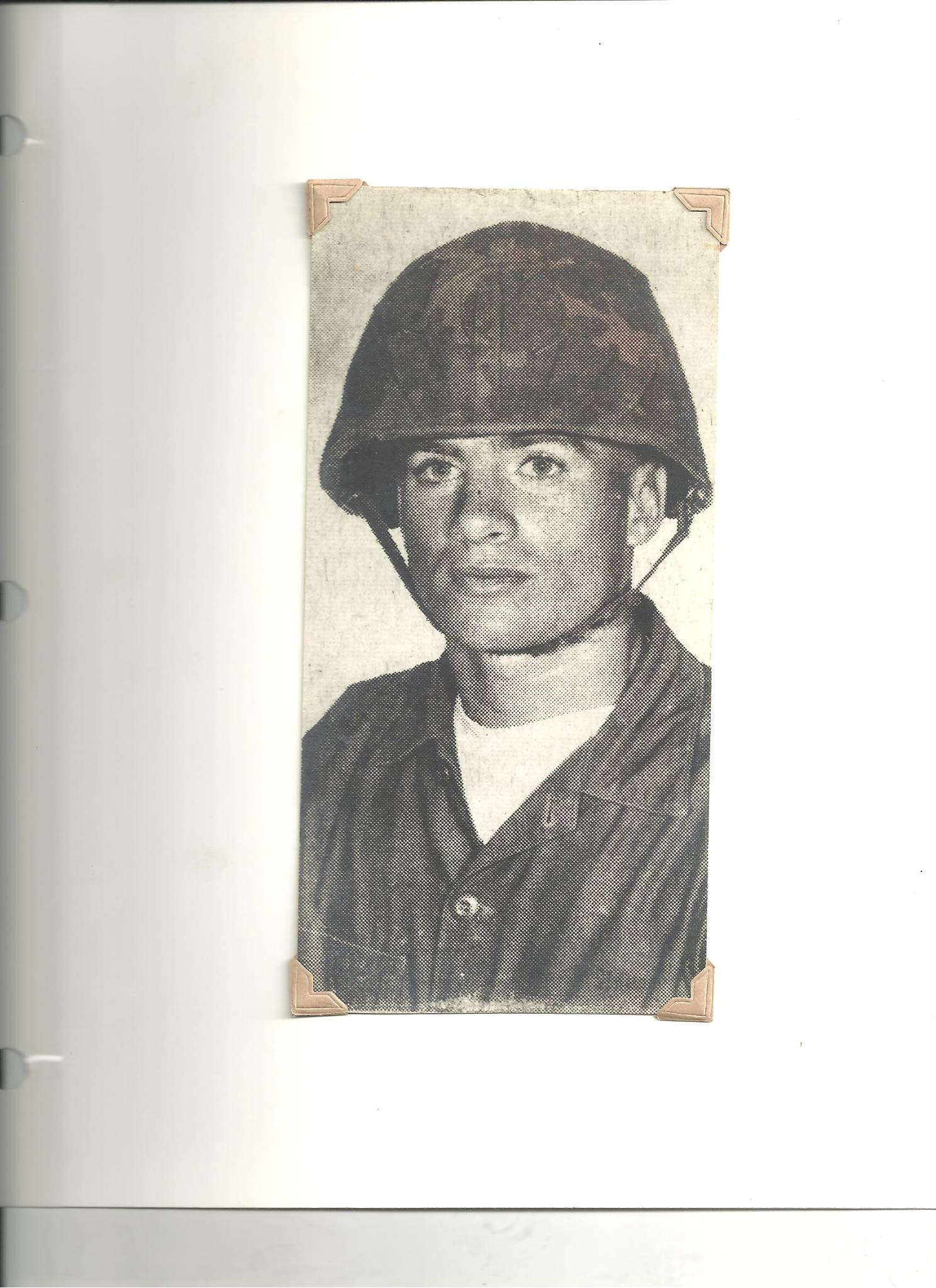

All five senses go on high alert. Even with all your combat training and the brainwashing they preach to you about how Marines should conduct themselves under enemy fire, you're still scared to death.

The impact of the projectile is deafening. Your body goes into shock immediately following the hit and the penetration into your skin. Once you've come to the realization that you've been wounded, you start looking for the blood. Try to patch it up. Stop the bleeding. Seeing a part of your body ripped open can be nauseating. But you have to see where it went in to wrap the hit properly.

Then "fight to live" kicks in.

You don't have much time to fool around with your wound. There's still a firefight going on. They're trying to get to you. To kill you. If you're able, you hunker down and pick them off as they run toward you. I hate saying so, but there's a kind of rush you feel when you shoot and see them go down.

I've actually screamed out loud, a jubilant "Yeah, Baby," as I've watched a guy die in front of me. I've asked God a million times to please forgive me for having had those feelings. I'm holding onto the hope that the Almighty, somehow, will give me a pass. I was taught that God is very forgiving. I truly hope so. Otherwise, I doubt I'll see you on the other side.

After you've gotten back into a prone position and begin firing back, you can't help it, tears start rolling down. Unstoppable.

They're not the kind you have when your feelings get hurt. They're more like tears Satan might cry. A mixture of fear, anger and an uncontrollable hatred for another human being. You grit your teeth and, through the blur of tears, you give it all you've got to make them suffer and die.

It wasn't the way I was brought up. There went my Christianity.

After a while, you can actually taste the metal in your body, the smell of your own skin burning. If you don't watch it, the magnitude and weight of it all can get the better of you. Never panic. Push yourself to go on the offensive. Again, numero uno is to survive. Stay alive and go home.

I had thought that I was up in the front by myself. I was an S2 Scout. I walked point. When the stuff hit the fan, I was usually stuck in the crossfire. I'd hit the ground and belly-crawl back to my guys. This day, all of us were pretty much pinned down. There was nowhere to go. I found cover behind a Vietnamese grave.

The Vietnamese farmers bury their kin out in the rice paddies. The more important the person was, the higher they built a knoll above the grave. I don't eat white rice.

All of a sudden, to my right, there's Duffy. He had made his way to the front line because he wanted to "take the fight to them." He had that reputation. I'd seen him around and had said hello. That was about it. Out of the blue and over the noise and chaos, he yelled to me, "Don't worry about nothin'. We got God on our side." Then a big grin.

We were no more than 10 feet apart.

He was a lanky-built, country-raised Baptist boy out of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, with a few more months left on his second tour. Like me, he wore a Fu Manchu moustache. He had crooked teeth and glaring eyes. He had been "in country" long enough that he had gone native.

Duffy got hit first. Then me. He took it in the leg. Me, my back and foot.

I crawled over to help him tie a makeshift tourniquet around his thigh. He wasn't bleeding that much. I had just gotten through telling him that his wound didn't look that bad, and then I got hit. I couldn't believe it.

After the smoke cleared, Duffy gave me a quick glance and started firing back. I took off my boot and wrapped my foot with my sock. Duffy was shooting and hollering at them, screaming like a madman.

Crazy as it sounds, watching him get after them like that cracked me up. He was full-blown. Here we were, wounded and in pain. Bullets whizzing. Grenades. And, of all things, I couldn't stop laughing. Duffy started laughing, too. Then we relocked-and-loaded and lit it up!

It's an understatement to say that you really get to know a guy in combat situations. Things happen so fast that one has only his instinct on which to rely. A man's pride and what courage he has show up. The fear goes away. You get it in your mind that you're going to fight till the end. You just kinda throw it all to the wind.

Duffy was a walking contradiction. He carried a little black Bible in his backpack, could quote the Scriptures and believed that God had wanted him to join the Marines and volunteer for Vietnam. He told me his mama had received the same message from the Lord. Duffy felt that he was on a mission for God. Yet he was one sadistic son-of-a-gun. Somewhere between crazy and out of his mind.

We became friends.

Duffy and I were medevaced out on the same chopper back to Dong Ha. But he went one way and me the other. He didn't come back out to the field. Nobody seemed to know what happened to him.

A few months later, my unit was choppered up to Cambodia, just over the border, to meet up with another group of Marines and help protect an artillery battery. Nixon was denying our troops were there. We made camp and dug in on a cleared-out knoll parallel to the big guns.

A Marine helicopter, attempting to deliver food, water, ammo and medical supplies to us, was shot out of the sky and tumbled head over teakettle down the side of the mountain and into the valley below.

It would take them three long days to make a successful drop.

In the meantime, they rationed out the water. It tasted like what you get out of a garden hose on a hot summer day. Add the malaria pills, and it tastes like you're drinking swimming pool water.

When you haven't eaten for three days, even C-rations sound good.

You can't call C-rations real food, per se. It's vacuum-sealed stuff in drab green tin cans left over from World War ll. Beans with frankfurter chunks in tomato sauce, beef in spiced sauce, beef slices with potatoes and gravy and, the worst of the bunch, ham and lima beans. We called it ham and expletives. It's awful stuff. Just a little better than prison meals.

I remember thinking that if those starving kids in Africa my grandmother used to tell me about when I didn't want to eat something on my plate were offered a big helping of C-rations, they would have said, "No, thanks."

I could have sold a hamburger over there for a hundred bucks!

The next morning, we were hot, tired, thirsty and hungry. Being up on that knoll gave us no shade. I was told to clean my rifle and get ready to go on patrol that night. I'm pulling gauze through the barrel, and up walks Duffy. And his big grin. We huddled up and talked the day away.

Duffy's plan for when he returned to "the world" was a simple one. Get a part-time job outside of the base they sent him to. Serve out the year he would have left in the Corps. Go back home and put a down payment on a dairy farm.

He was convinced that being a dairy farmer was what God wanted him to do. So was his mother. She was going to move out of Duffy's older sister's home and come live with him. He had great love for his mother. She lived by the Bible. Duffy doubted his mom would ever marry again.

Furthermore, he had a theory that having cows around would keep him calm. Such was the case when his father abruptly left and never came back. It was just him and his mom. He told me that milking their cows had relaxed him.

Day 2 of nothing to eat. I had a plan. Get permission from Captain Fox for me to go outside the perimeter and shoot a rock ape. They're about 4 feet tall and kinda look like miniature gorillas. More tan in color. They were running all over the place.

I had found an old piece of tin just perfect for grilled "T-bone monkey." Duffy agreed to chop it up and cook it. We both reckoned that rock ape probably tasted like chicken. I remember Duffy saying, in his nasal-twanged Alabama drawl, "It kain't taste no worse than squirrel."

I shot a good-size ape within minutes.

After the fire got going, the monkey pieces started cooking. The smell ran across the top of the hill. In fact, it smelled like chicken kinda. Duffy was flipping the meat and whistling. We were on to something. Not long from now, he and I and some of our chosen few were gonna be chowing down on some monkey meat that was, hopefully, going to taste like chicken.

A crowd gathered. Duffy cut off a piece and stuck it in his mouth. While he was chewing it, he smiled and said, "Not bad." Hallelujah! Jubilantly, I yelled out, "Let the feast begin!"

I took a bite and swallowed it. It tasted as though the monkey was still alive. It was like ingesting stench. The glob hit my stomach and was on its way back up. The same for the chosen few. We all engaged in synchronized projectile urping. In between their internal eruptions, the guys were cursing me. It went on for a while.

Duffy never got sick. And from time to time, he went back over to the tin and nibbled. Iron guts, those Southern Baptists.

The next day, just before dusk, they made the supply drop. We were starving. Even ham and lima beans sounded good. For the rest of the time I was in Vietnam, they didn't let me forget about the monkey meal. Duffy was rotated back to the states a little before me. We lost touch. I called every Duffy in Tuscaloosa years ago. It was difficult in that I never knew his first name. No telling where he ended up.

Knowing Duffy, he got that farm and some cows. He's probably buried his mom by now. I don't know why, but I get the feeling that he's by himself. Sitting on his front porch and watching people go by. They may look over at him and see an aging man. He may have put on a few pounds. There's probably nothing about him that shows signs of the pure warrior he was known to be. Unless you get up close. Close enough to see that glare in his eyes.

Hey, Duffy, if you're out there, I hope you've been having a good life. If you ever get to feeling a little down, or if the demons show up, don't worry about nothin'. We got God on our side.

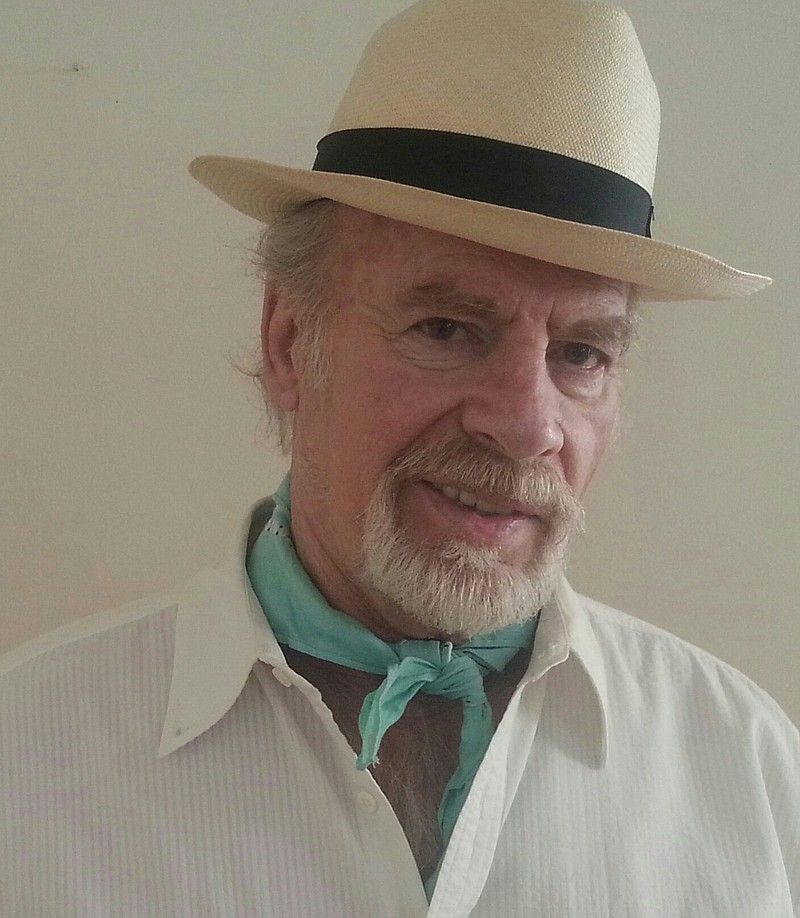

Bill Stamps spent four decades in the entertainment business before moving from Los Angeles to Cleveland, Tenn. Contact him at bill_stamps@aol.com or through Facebook.