(This story is dedicated to my friend, Randy Fox, a fellow Vietnam veteran, dealing with PTSD.)

I really couldn't blame Dad for not wanting me to hang around town. I'd been a handful to deal with all through my high school years. If they'd had a trophy for the kid who got into the most trouble, I'd have won by a landslide.

When they told me after my one and only semester of college that I hadn't made the cut, I packed up and came home. I guess I should have taken education more seriously. Vietnam was revving up.

The next thing I knew, I was meeting the Marine Corps recruiter in Dad's office at the radio station. I signed up for four years. They gave me 90 days to get my affairs squared away.

Right after the first of the year, they mailed me a package. Inside was a government-issued, one-way Greyhound bus ticket and orders to report to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, in March 1967.

There wasn't much for me to do. When you get on that bus, all you need are the clothes on your back and a few bucks in your pocket. Everything in your future is provided to you by Uncle Sam, right down to your skivvies and a toothbrush.

I used my 90 days wisely. I took out as many girls as I could. Hands down, telling a girl "I hope I make it back" is the very best bachelor line I've ever spoken. Those were three of the best months of my life.

Early that rainy March morning, Dad drove me to the bus depot. We had a few minutes before boarding. I don't remember what we talked about. It was awkward chitchat. I wondered if it crossed Dad's mind that I might be heading off to war and never coming back.

In the late 1950s, after he got off the air, Dad drove over to Franklin, Tennessee, and brought my two younger brothers and me back to Cleveland, Tennessee, to live with him. Mom had some serious personal problems. She just wasn't capable of taking care of us any longer.

With the exception of two short summer visits and an hour on a Christmas morning, we hadn't had much contact with Dad in the past few years. It was quite apparent that Dad had been living a much better life than Mom and us boys.

When kids are put in the middle of their parents' differences, unfortunately sides get chosen. At the time, I favored my mother, but I recognized that Dad provided stability and security that Mom never could.

Through the years, Dad and I developed a deep and loving relationship. As a matter of fact, I loved him very much. Still, I couldn't help myself from having mixed feelings about the way he had treated Mom. I guess it showed.

Also, it hurt that Dad was rather reserved with his heart when it came to me. Things got better between us in the final 10 years of his life.

Just before I got on the bus, uncharacteristically Dad gave me a tight hug and kissed the side of my face. He had tears and a little tremble in his voice.

He told me, "You're leaving as a boy, and you'll come back a man. Be the best Marine you can be." I thought about that all the way down to San Diego. I decided that was exactly what I was going to do.

Boot camp was as tough as I'd heard it was. They tear you down and build you back up in three and a half months. They toughen you up physically and mentally. Two days before graduation, the platoon commander had us fall in outside our Quonset huts and read off our MOS (military occupational specialty) and where we were heading.

Most of the guys were ordered to report to staging for more combat training, then saddle up and board a flight to Vietnam. Their MOS was 0311. Ground forces. Grunts. The heart and soul of the "lean, green, fighting-machine." God has a special place in his heart for grunts.

Out of the entire battalion, I was the only one given an 0231 MOS. Intelligence. I had no idea what I'd be doing. My orders read for me to report to the commanding officer of the 5th Engineers Battalion, 5th Marine Division, Camp Pendleton, California.

From there, I was sent to Vietnamese Language School and then intense training at guerrilla warfare school. After all that training, I was assigned a desk and a typewriter. I was an "office pinkie," typing secret clearances and reduced to complete embarrassment.

I kept requesting that I be sent to Vietnam. I hadn't joined the Marines to sit behind a desk. Finally, almost a year later, I received my orders to report to staging.

We were less than a week away from shoving off for Nam when I got the word that my brother, Ricky, had fallen off a cliff and into the river. Three weeks after we buried him, I was in-country. I took Ricky's spirit with me.

We flew into Da Nang. The Viet Cong were dropping mortars on the airstrip as we landed. My heart was racing. I told myself to just cool it. I drew strength by remembering lines from Rudyard Kipling's letter to his son. A poem titled, "If." Most especially, the line about keeping your head about you while the rest of them are losing theirs.

I'd never seen anything like it. Structures and helicopters on fire and the first of many dead Marines I would see. Bodies were strewn out and lying on the runway. Their stillness was eerie. It was like the Almighty had turned off the sound and created a small capsule of stand-still time for my fellow Marines' souls to ascend to the sky and beyond.

Patriotic families would soon hear the news of their sons' death and, through their tears, look up to God and scream at him, "Why ?"

Like magic, between my extensive combat training, Ricky in my heart and Dad's ringing words to me about being a good Marine, I became calm and focused.

The next morning, I jumped on a helicopter and was on my way north to Quang Tri. I landed, checked in, got issued combat gear, a rifle and a pistol and some new jungle boots. Two days later, I was choppered out to "the bush."

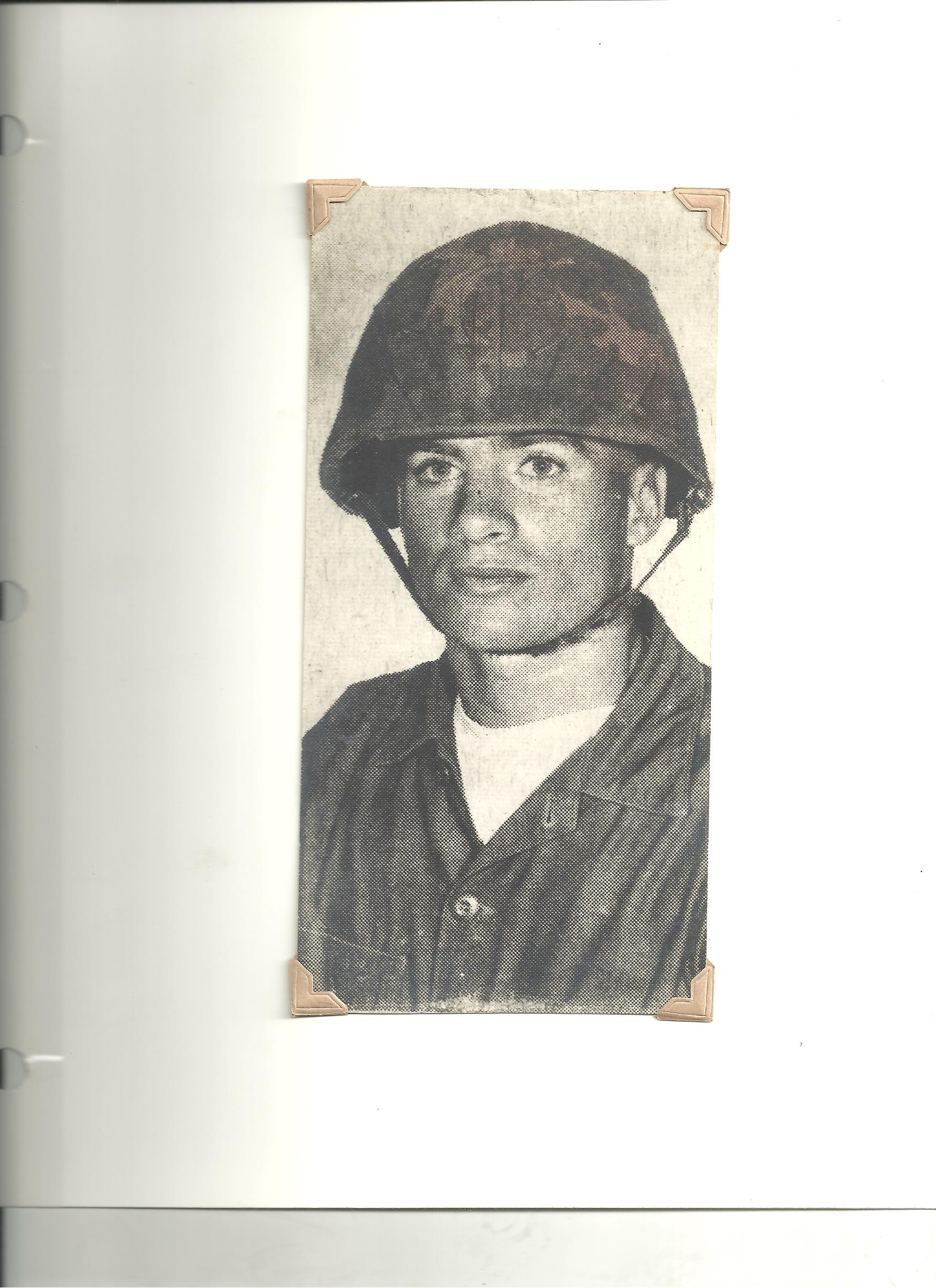

I replaced a guy named Rolfing as the new S-2 scout for Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. No more typewriters for me. I was with the grunts. I was good with that. Finally, I felt like a true Marine.

I walked point with three North Vietnamese scouts who were assigned to me: Lekien, Thom and Tong. They'd been captured, rehabbed and sent back out to the field to assist with interrogation, detect ambushes and booby traps and help guide us through the jungles.

I trusted them, but not that much. They weren't working for America by choice. It hadn't been that long back that they were trying to kill us.

I decided from the get-go that if I detected anything strange about their behavior, I'd kill them. When you're out there, scared, uptight and tense, survival consumes your brain. All you want is to get back home. You'll do whatever it takes to keep yourself alive.

Less than two months in-country, I took my first hit, May 5, in the village of Dia Do. I bled a lot and thought I was going to die. It wasn't that bad. I was medevaced out, got patched up and was back with the guys within a few days.

I'd written to my family and told them there was no reason for concern, that I was sitting behind a desk, "in the rear with the gear." I didn't want anybody to worry, especially Dad. He had just buried one of his sons. His heart was already broken enough.

I had no idea that whenever you get a Purple Heart that your family is informed. The same recruiter who signed me up made a visit to Dad. My cover was blown. The recruiter made two more trips to tell Dad I'd been hit. Three "hearts" in less than nine months, and they sent me home.

About a year before Dad passed away, we were talking on the phone. I remember that we laughed a lot. Just before we hung up, he told me that he was proud of me and how worried for me he'd been when I was in Vietnam.

I told him that he was the reason that I made it back because I had been the best Marine that I could be. My father cried.

God, please bless all families with loved ones in the armed forces and pass on our respect and gratitude to those brave men and women, already up there with you, who gave their lives for our country. And please tell all the Marines I said, "Happy Birthday."

And please, please, continue to bless America.

Bill Stamps' books, "Miz Lena" and "Southern Folks," are available on Amazon. For signed copies, email bill_stamps@aol.com.