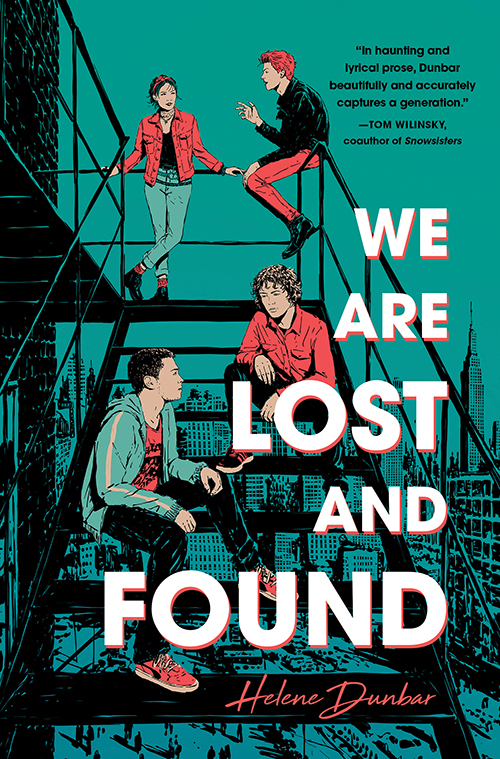

"WE ARE LOST AND FOUND," by Helene Dunbar (Sourcebooks Fire, 304 pages, $18).

In 1983 Ronald Reagan was president, Stonewall was ancient history, and AIDS only a rumor of a strange "gay plague." It was an intoxicating, perilous time to be a teenager in New York, aching for love and freedom. In Helene Dunbar's latest young-adult novel, "We Are Lost and Found," Michael, the narrator, and his friends James and Becky struggle to navigate these dangerous waters.

Michael's older brother, Conner, has already been kicked out of their parents' Upper West Side home for coming out in a speech at his high school graduation. Cut off from his family and his college fund, Conner is deep into the gay bathhouse and bar scene of the early 1980s. Michael knows that he, too, is gay, but he keeps his head down and his heart to himself, enduring his father's homophobic rages.

Yet he has dreams and a penchant for list-making. His first list, a parody of a teacher's assignment, is:

* Fall in love.

* Figure out who the hell I am.

* Have sex without catching something.

* Repair my family.

* Escape.

Meanwhile, he loses himself dancing with his friends in their favorite Hell's Kitchen club, The Echo, to the music of new artists like The Clash, Madonna and Talking Heads. He's sure nobody will even notice him next to beautiful, exotic James or vivacious Becky, whose boyfriend is one of the Guardian Angels, the red-beret-wearing citizen crime fighters who have become folk heroes in the city. But even though Michael feels overshadowed by his companions, their friendship sustains him.

Friendship seems like enough - until Gabriel walks into The Echo one night and has eyes only for him. Michael's armor begins to crack, and he confesses his longing to himself and the world in anonymous scribblings on the wall of the ex-telephone booth "fear room" at his school: "I met someone, I write. Someone I really like and ... I leave it hanging on the ellipse because I don't know what the 'and' is."

Michael's fear-tinged desire must have been experienced by many young gay men at the time, though no one could have known about the terrible epidemic to come. In an afterword to "We Are Lost and Found," AIDS activist Ron Goldberg writes that the disease was just a blip on the radar of gay life of New York in 1983, less of a worry than being beaten up for holding a lover's hand anywhere outside of Greenwich Village. The first mass-media warning was sounded in 1981 with a New York Times article headlined "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals." By the end of 1983, more than 3,000 cases of the disease had been reported, and it had a new name: "acquired immunodeficiency syndrome." Since then, around the world, 35 million people have died of AIDS.

Dunbar, who came of age in the early 1980s, is the author of three previous YA novels: "Boomerang," "These Gentle Wounds" and "What Remains." In a career that includes journalism, music criticism and marketing, she also wrote grant proposals for AIDS response programs. In this novel, she blends both the fear and longing of first love with her deep knowledge of the time and the disease that haunted a generation of young lovers, gay and straight.

For more local book coverage, visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.